In 1975, the first United Nations World Conference on Women took place between 19 June and 2 July in Mexico City, bringing together individuals from a wide range of backgrounds with the goal of promoting gender equality. The World Conference of Women (WCW) was the capstone event of International Women’s Year, the UN’s response to the transnational women’s liberation movement sweeping the globe.

Mexico City had not been the first choice of venue— the event’s initial host country, Colombia, had backed out after not being able to come up with the necessary funding.

The Mexican government then stepped in, seeing the conference as a way to elevate its standing in the international community, particularly in comparison with the United States. In Mexico, after all, gender equality had been guaranteed since 1917 in the Mexican Constitution, while the United States was still struggling (and would eventually fail) to pass an equal rights amendment.

Additionally, Mexican leaders wanted to showcase Mexico’s impressive International Women’s Year Program and use it as evidence that developing nations did not need to be under the supervision of industrialized countries when it came to laws of equality or execution of UN programs.

The United Nations General Assembly agreed upon three primary objectives for the conference: gender equality and an end to gender discrimination, integration and participation of women in development, and increasing women’s contribution to world peace.

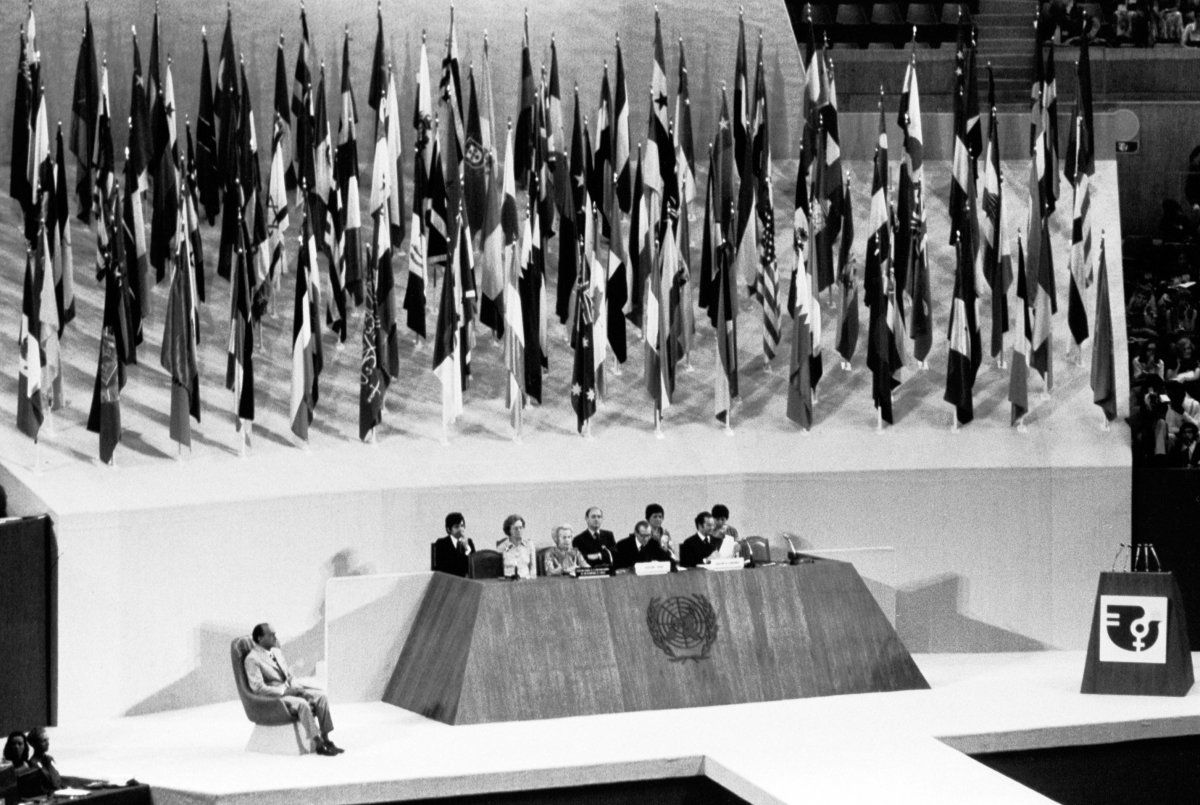

In addition to the official conference, there was a parallel forum called The International Women’s Year Tribune, where 6,000 non-governmental organizations (NGOs) discussed various issues, although without the authority to implement any resulting action plans. The conference proceedings were hosted in the Gimnasio Olímpico Juan de la Barrera, an indoor arena that had previously served as one of the sites of the 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympics.

The inauguration ceremony of the 1975 World Conference on Women (UN Photo by B. Lane).

Looking back, it is easy to see the optimism participants felt at the conference.

The UN managed to bring 133 governments together, most of which were led by female delegates. Margaret Bruce, the Deputy Secretary General of both International Women’s Year and the World Conference on Women told The New York Times that their goal was “to do such a good job in Mexico City that people won’t giggle anymore whenever they talk about women.”

Helvi Sipilä, a Finnish diplomat who served as the Secretary General of WCW, explained that the conference would pay attention to matters such as “political decision making, educational opportunities, economic opportunities, a different status in civil courts and all questions of maternity.”

The enthusiasm that Bruce expressed along with the confidence to tackle the topics Sipilä mentioned captured the powerful spirit of that moment. Women’s issues were finally being taken seriously.

West German stamps commemorating 1975 as the UN's International Women's Year.

At the conference itself, however, that buoyant mood was quickly tempered as delegates revealed a variety of differing points of view. The representatives brought their own worldviews, but these were often heavily influenced by male politicians back home. Arvonne Fraser, president of the Women’s Equity Action League, 1972-1974, recalled that “individual people didn’t speak at these conferences, governments spoke.”

The restive geopolitical climate of the 1970s weighed heavily on the proceedings in Mexico City. Nations that had recently gained their independence were caught up in the midst of nation-building while also considering the international ramifications of the Cold War.

The Israeli/Palestinian conflict, the apartheid regime of South Africa, the CIA-backed coup that toppled Salvador Allende in Chile, and the Vietnam War all shaped the viewpoints of the conference’s attendees and the nations they represented.

The most significant rift at the conference was between “First World” and “Third World” nations. Representatives from the global south perceived their Western counterparts as having overlooked colonial, post-colonial, and racial issues by focusing exclusively on gender questions.

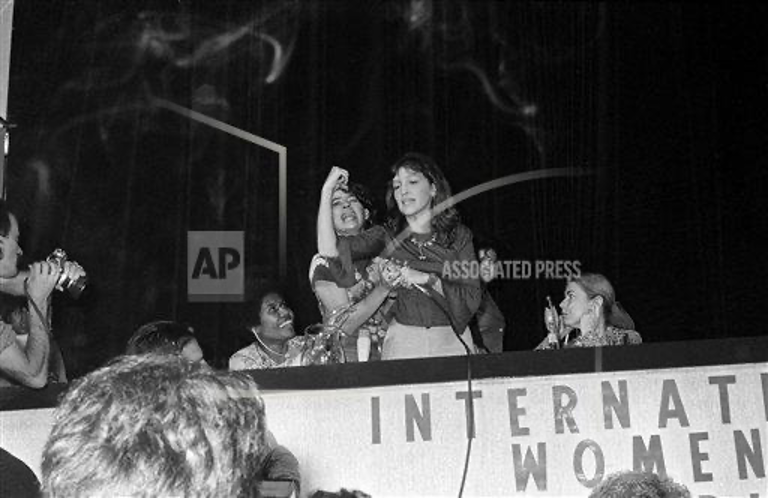

Conflicts between delegates received breathless coverage in the international media.

Ten days into the conference, the Associated Press printed an image of two Latin American women, Adriana Puiggrós (Argentina) and Maria Antonieta Rascón (Mexico), fighting over a microphone. The image’s caption suggested that the altercation had occurred among delegates at the official conference, when in reality it had taken place at the unofficial NGO Tribune. After the microphone fiasco, organizers attempted to push back against media depictions by holding a “unity panel,” but the disagreements continued.

Adriana Puiggrós (center) and Maria Antonieta Rascón (left) photographed struggling over a microphone on June 27, 1975 at the Tribune of the WCW in Mexico City. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

These frictions, however, did not prevent the delegates from achieving significant goals, most notably the adoption of two official documents: the World Plan of Action and the “Declaration of Mexico on the Equality of Women and their Contribution to Development and Peace.”

The World Plan of Action provided governments with a framework to follow in order to ensure that women had equal access to resources such as education, employment, housing, and family planning within ten years. It set a deadline of five years to meet a set of minimum requirements. The Declaration of Mexico on the Equality of Women and their Contribution to Development and Peace articulated a set of principles concerning women’s integration into each country’s development processes and increasing women’s participation in politics.

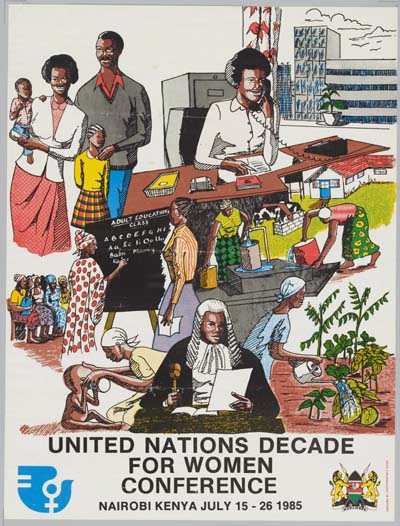

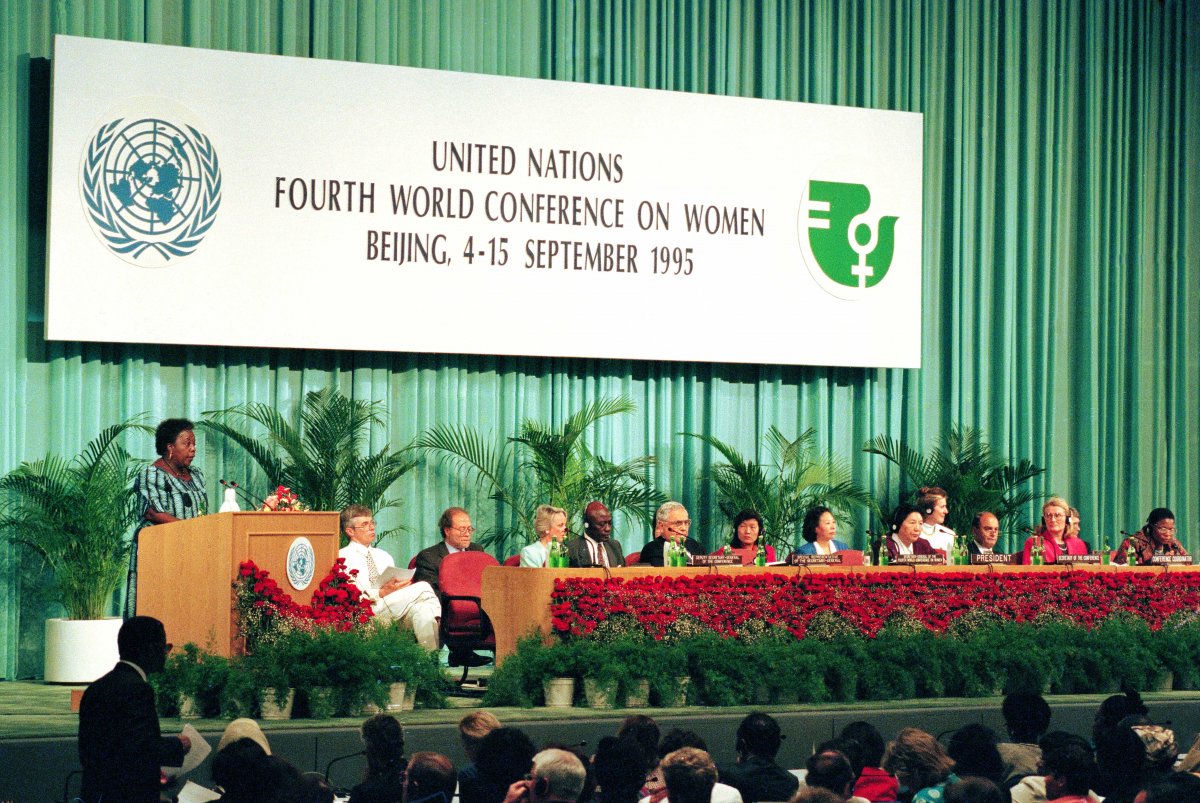

Most importantly, the 1975 Women’s Year World Conference helped set the stage for three further World Conferences on Women in Copenhagen (1980), Nairobi (1985), and Beijing (1995). At the Beijing meeting, the 68 attending nations moved beyond merely developing guidelines and officially committed to implementing concrete actions in support gender equality. For example, the United States announced a six-year plan to spend $1.6 billion on an anti-violence program.

The United Nations Economic and Social Council’s ten-year 2005 review of the results of the Beijing Declaration and Platform of Action reveal how the four World Conferences on Women had spurred reform in participant countries.

For example, Armenia, Denmark, and France created deputy or full minister positions in charge of topics related to women and gender equality. Other countries such as Brazil, Kyrgyzstan, Djibouti, and Ethiopia moved their offices committed to gender equality to a more central location. Many countries including Austria, Bulgaria, and the Czech Republic established equal employment opportunity offices, and other countries published statistical reports evaluating topics such as violence against women, health, and employment.

The report also made it clear that despite the progress countries made, significant challenges remained. Weak national institutions responsible for promoting gender equality, a widespread belief that gender equality was less important than other matters, and lack of funding remain obstacles in numerous places worldwide.

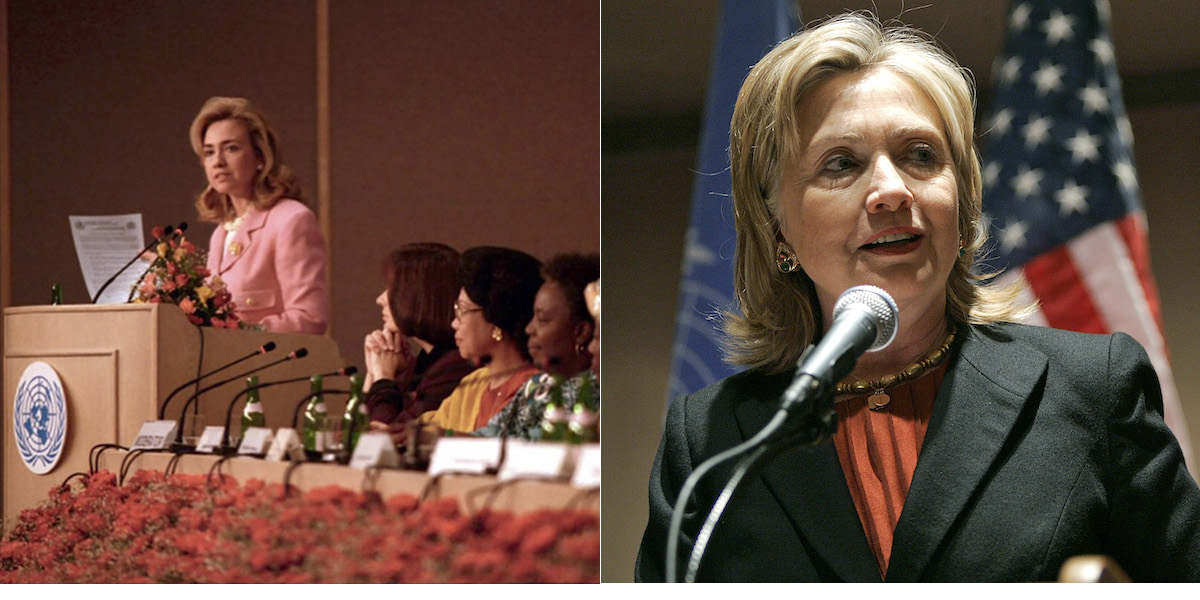

First Lady Hillary Clinton speaking at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, September 05, 1995 (left); Secretary of State Hillary Clinton speaks at UN Headquarters in honor of the fifteenth anniversary of the UN World Conference on Women in Beijing, March 12, 2010 (right, UN Photo by Paulo Filgueiras).

Ultimately, the report highlighted that many countries had adopted a national gender equality agenda, but it was clear that enacting, enforcing, and funding a coherent plan of action tailored to each individual country was quite difficult, especially when the topic continued to be perceived as nonessential comparted to other matters.

Today, a rising pandemic has highlighted the weaknesses of our economic order, and drawn attention to the vast amount of work that women contribute in and outside the home, the goals and objectives of the Mexico City World Conference on Women remain as important as ever.