On July 24, 1923, negotiating parties at the Swiss resort town of Lausanne signed the final treaty of the First World War—the Treaty of Lausanne. After ten months of intense negotiations, the parties finally reached an agreement over the terms of a settlement, which would replace the punitive peace treaty dictated upon the Ottoman Empire three years earlier. Of all the treaties signed after WWI, the Treaty of Lausanne was the only one negotiated and, perhaps more importantly, it is the only treaty of WWI still in force today.

Lausanne marked the end of a long and devastating period in the Middle East. Between 1911 and 1922, the Ottoman Empire suffered almost constantly from wars. The Ottomans experienced humiliating and destructive losses at the hands of Italy (1911) and the Balkan states (1912-13), costing the empire its remaining territories in Africa and most of Europe.

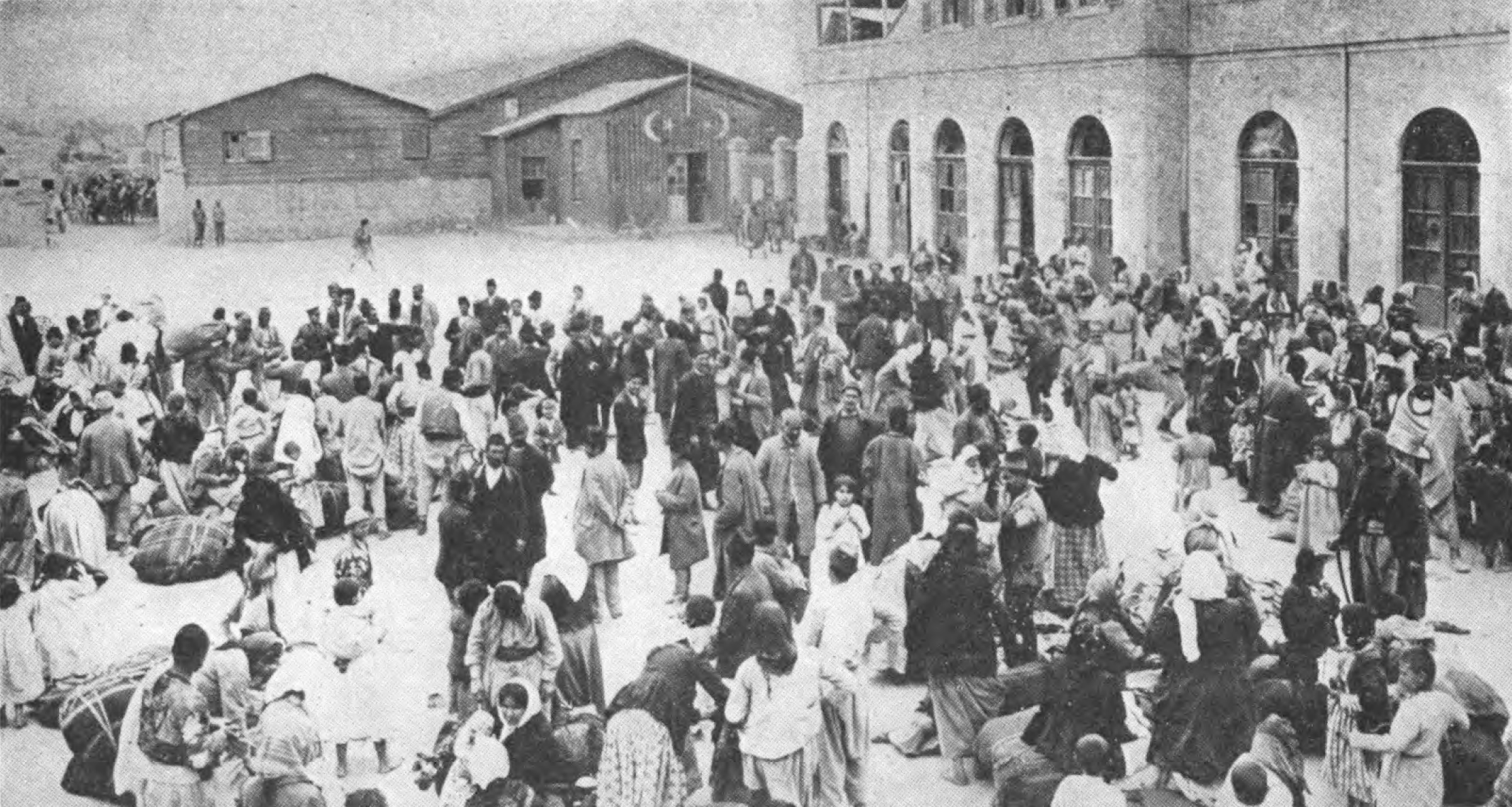

These provinces, home to nearly four million inhabitants, had been under Ottoman rule for centuries. The Balkan Wars saw atrocities committed against civilians on a massive scale. The Ottomans’ defeat also precipitated the migration of hundreds of thousands of refugees under deplorable conditions, from their homes in the Balkans to Anatolia and other Ottoman provinces.

However, the overall impact of these conflicts paled in comparison to the First World War.

The magnitude of death and destruction of the Great War devastated the Ottoman Empire. By the end of the conflict, the empire had lost millions of its former subjects and most of its Arab provinces—comprising contemporary Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine—having been reduced to the lands of Anatolia.

The social capital of the region had also been depleted by military casualties, ethnic cleansing, population movements, epidemics, and hunger. Virtually every Ottoman, regardless of age, gender, or ethno-religious affiliation, had to cope with deprivation, bereavement, and hardships of all kinds.

World War I also destroyed the foundations of inter-communal coexistence in the Ottoman Empire. Non-Muslim and non-Turkish minorities (such as Greeks, Kurds, Arabs, and others) were alienated from the state due to intrusive wartime measures and forced resettled in distant provinces.

“Four miserable years of tyranny,” as historian Salim Tamari has observed, erased “four centuries of a rich and complex Ottoman patrimony” in the Arab provinces of the empire. The cataclysm of the war and the destructiveness of wartime policies eroded the Ottoman state’s legitimacy.

For Ottoman Armenians, however, WWI marked the devastation of a people. In the early months of the conflict, the Ottoman army and government, under the control of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP or the Unionists), first resorted to limited security measures to eliminate perceived threats to the empire’s war effort.

In its initial phase, the Unionists’ treatment of Armenians resembled other belligerents’ treatment of their own so-called “domestic others.” These policies originated from the concern that those of other ethnic backgrounds might sympathize and collaborate with the enemy and engage in treacherous activities.

After a certain point, however, the Unionists’ objectives transcended the original limited goals and became more comprehensive in scope, total in intent, and future-oriented in outlook. They did not hesitate to uproot more than a million people and exterminate a significant portion of them. In this regard, the destructiveness of the Unionists’ genocidal demographic engineering policies distinguished the Ottomans’ wartime experience from that of many other belligerents. The disaster that befell Ottoman Armenians was unmatched in its extent and lethality.

When the war finally ended, the Ottoman Empire plunged into a painful period of instability and uncertainty. The collapse of the ruthless wartime regime, the arrival of the Entente troops and de facto occupation of the imperial capital, and the global spread of the Wilsonian promise of national self-determination politically energized the Ottoman minorities as never before.

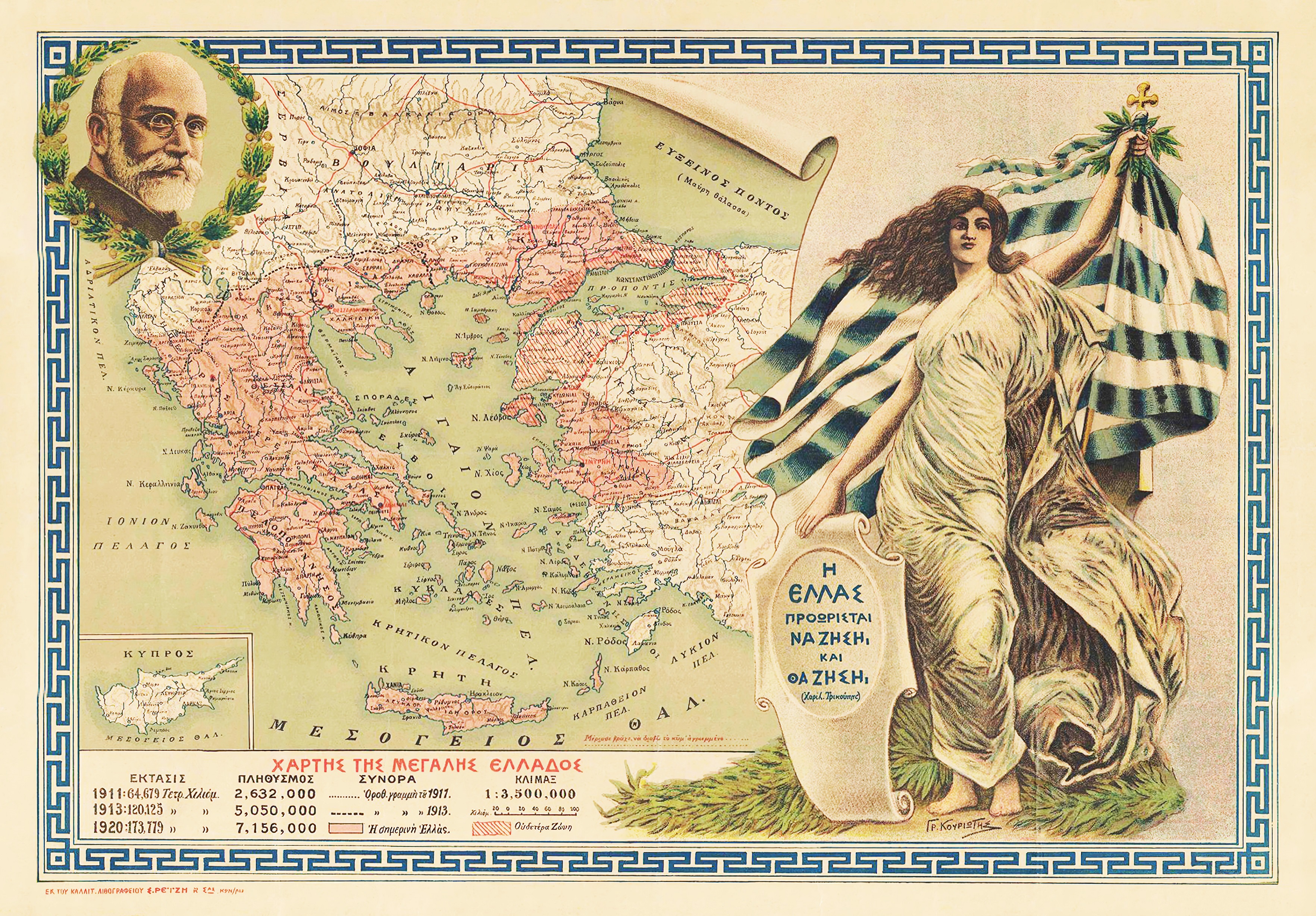

For many Ottoman Greeks, self-determination meant union with Greece. At the Paris Peace Conference, Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos negotiated for Greece to obtain a zone of occupation around Smyrna/Izmir. Meanwhile, Ottoman Armenians aimed to establish an enlarged, independent Armenia, the boundaries of which would extend well into eastern and central Anatolia.

From the talks’ beginning, the Ottoman Turks—the empire’s demographic majority— knew they could count on very few supporters at the Paris Peace Conference. In the victors’ minds, the war would have ended much earlier had the empire remained neutral. They were also furious at the Ottomans for their wartime treatment of non-Muslim minorities, particularly the Armenians.

For the peacemakers, the long record of Ottoman misgovernment, culminating in wartime massacres, demonstrated the Ottoman Turks’ incapacity to properly administer a multi-ethnic, multi-religious population. The general consensus in Paris was that certain regions should be severed from the rest of the empire and placed under the mandatory tutelage of “advanced nations” on behalf of the League of Nations.

President Wilson summarized the peacemakers’ position bluntly: “It is the purpose of the Conference to separate from the Turkish Empire certain areas comprising, for example, Palestine, Syria, the Arab countries to the east of Palestine and Syria, Mesopotamia, Armenia, Cilicia, and perhaps additional areas in Asia Minor, and to put the development of their people under the guidance of Governments which are to act as Mandatories of the League of Nations.”

Although they sensed the intense anger and contempt directed toward them, the Ottomans still harbored hope that a fundamentally reformed new international system based on Wilsonian principles would eventually accord them a dignified place in the new postwar world order. To their great dismay, however, the Conference sanctioned the Greek occupation of western Anatolia in May 1919, which marked a dramatic turning point in the twilight years of the empire.

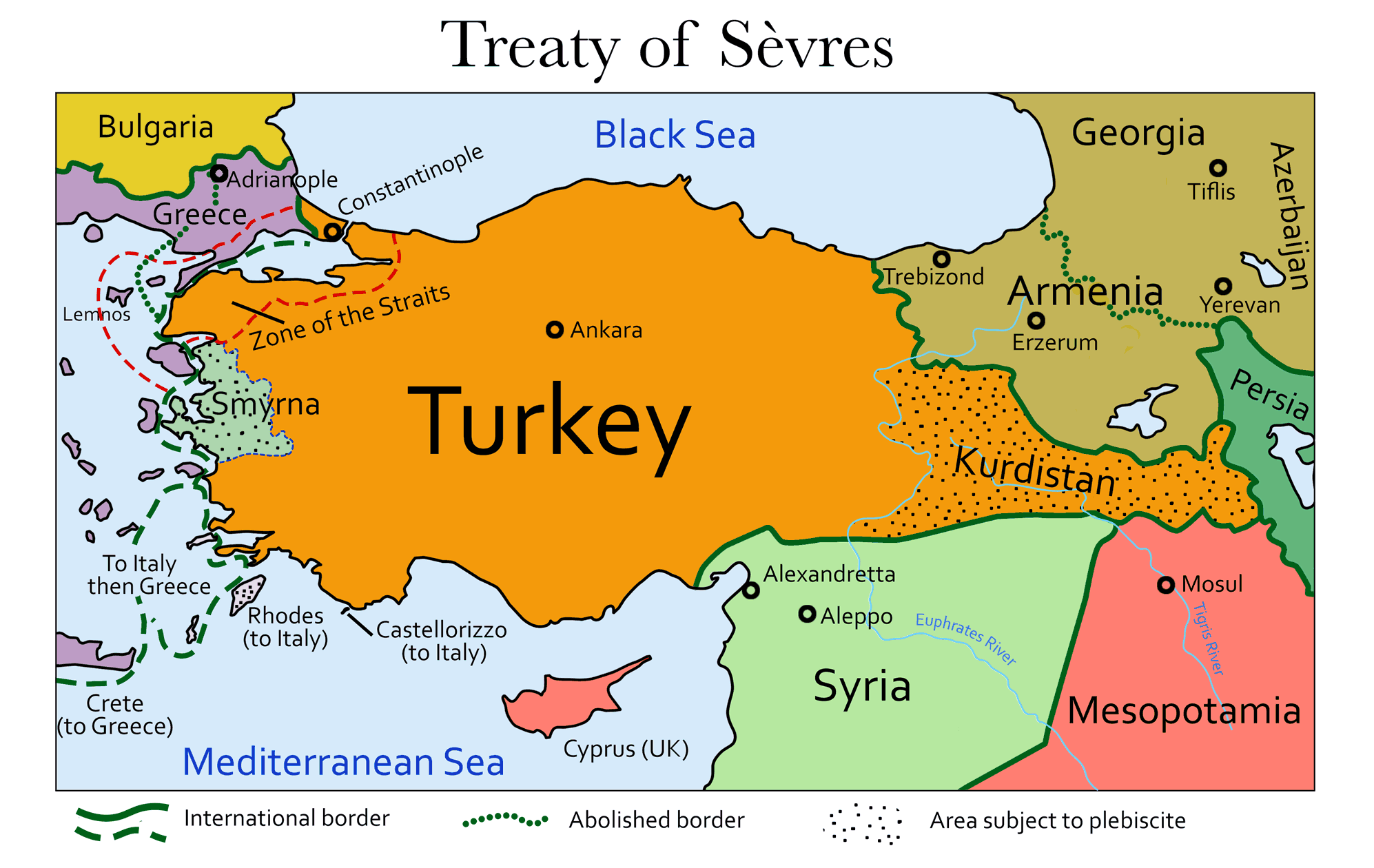

In the final months of 1919, the Ottomans’ hopes of maintaining their empire faded. After the Conference’s imposition of a particularly harsh peace treaty on the Ottomans, the subsequent Treaty of Sèvres (August 1920) turned their hopes to fury.

The treaty stipulated the division of Anatolia into European spheres of influence, carved out territories for Armenia and Kurdistan, and formalized the assignment of Middle Eastern mandates to Great Britain and France. By then, the nationalists under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha (later Atatürk) had managed to organize an increasingly effective resistance movement in Anatolia.

The nationalists also began to pursue an extensive and systematic “policy of unmixing” the empire’s remaining ethno-religious communities from one another. This policy ultimately sought to create new ethnographic realities on the ground to make it practically impossible for Greeks and Armenians to claim territorial sovereignty on any part of Anatolia based on demographic majority. By September 1922, they had ejected the occupying Greek army from Anatolia.

By October 1922, the nationalists forced the parallel government in Istanbul to resign. The next month they abolished the Ottoman dynasty, ending one of the longest-lasting empires in history. The 36th and last sultan of the Ottomans, Mehmed VI, left the empire on board a British battleship.

The nationalist victory led to the revision of the Treaty of Sèvres. While the clauses of this treaty pertaining to the empire’s Arab provinces remained unchanged, those regarding Anatolia and Thrace were replaced in a new peace treaty signed in Lausanne. Via the Treaty of Lausanne, the international community extended full legal recognition to the nationalist regime, acknowledged most of its territorial claims, and formally accepted its right to secure sovereignty over these territories.

The Republic of Turkey, established in October 1923, became the first sovereign state in the Middle East.

However, the Treaty of Lausanne also marked the official end of long-lasting Ottoman co-existence. It stipulated the largest forced population exchange in history until the Second World War. Approximately 900,000 Ottoman Christians and 400,000 Greek Muslims were forcibly resettled in a “homeland” most had never even visited.

The overall perception of Lausanne’s bloodless unmixing as “success” would make it a point of reference in post-World War II peace settlements and the partition of India in 1947. While a foundational milestone in the making of the modern Middle East, the Treaty of Lausanne thus has an unmistakable global importance.

![]()

Learn More:

The Lausanne Project (https://thelausanneproject.com/)

Jonathan Conlin & Ozan Ozavci (eds.), They All Made Peace, What's Peace? The 1923 Lausanne Treaty and the New Imperial Order (London: Gingko Library, 2023)

Hans-Lukas Kieser, When Democracy Died: The Middle East's Enduring Peace of Lausanne (Cambridge UP, 2023)

Jay Winter, The Day the Great War Ended, 24 July 1923: The Civilianization of War (Oxford UP, 2023)

Michelle Tusan, The Last Treaty: Lausanne and the End of the First World War in the Middle East (Cambridge UP, 2023)