Published just before the November 2016 U.S. presidential election, Stephen R. Porter’s Benevolent Empire: U.S. Power, Humanitarianism, and the World’s Dispossessed comes at a time that many observers of U.S. domestic politics see as the twilight of America’s century as a global humanitarian power. Actions taken by the Trump administration—namely the ban on immigration from several Middle Eastern countries and the temporary suspension of Syrian refugee programs—seem to confirm that the United States will not take the lead in handling the humanitarian crisis in that region.

But as Porter’s book shows, the U.S. government has had a murky, even “schizophrenic,” view of its commitment to the world’s dispossessed. Although the United States consistently justified its ascendance as a global hegemonic power through far reaching humanitarian projects (including global food relief and health campaigns in addition to refugee programs), its international posturing often clashed with domestic political currents. Porter hones in on refugee aid as a major pillar of U.S. humanitarian soft power and shows how efforts to help refugees in particular have rubbed against countercurrents of economic and racial anxiety.

The author frames his narrative within the “short American century,” beginning with the country’s humanitarian awakening during the First World War (1914-1918), when the desire among American citizens to assist populations suffering from war and occupation in Europe outperformed the federal government’s institutional capacity to marshal resources. During the war, volunteer agencies like Herbert Hoover’s Committee to Relieve Belgium and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee sent millions of tons of food and material aid to the victims of war in Europe.

|

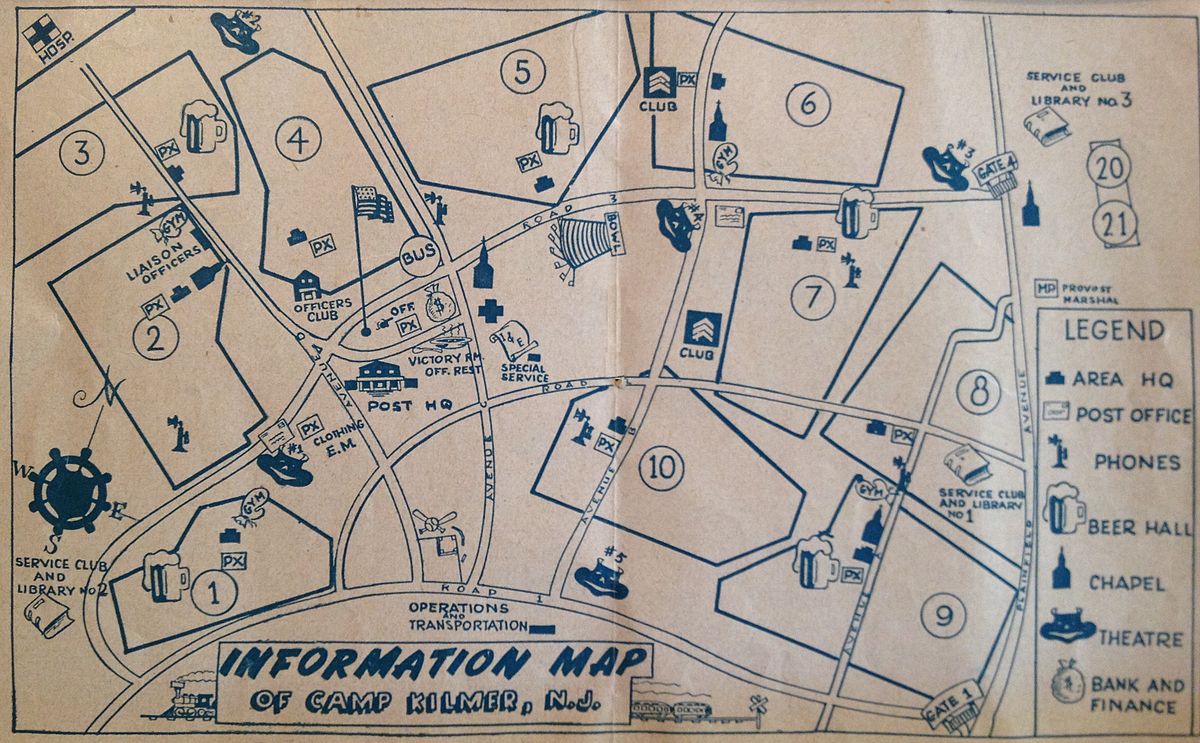

| A sketched map of Camp Kilmer, a camp in New Jersey that housed 30,000 Hungarian refugees in the 1950s. |

Although American relief had helped stabilize Europe during and after WWI, a wave of restrictions on immigration, beginning with Canada’s immigration law of 1923, closed the door on many European Jews who would have emigrated in the coming years. As the situation in Nazi Germany grew more disturbing, especially with the 1935 Nuremburg laws that stripped Jews of their citizenship and the 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom, philanthropic agencies understood that material aid would not ensure the well-being of Germany’s Jews and began lobbying to ease barriers to immigration.

According to Porter, the pivot in refugee policy came in 1938 when George L. Warren, an advisor on U.S. refugee affairs, issued an inconspicuous but influential policy memorandum to the State Department. Up until the late 1930s, immigrants required letters of sponsorship from private sponsors as proof of financial stability. In the aftermath of the Great Depression, when entitlement to public funds coincided with a sense of national belonging, policymakers worked to keep migrants off of public funds.

Warren, however, recommended that immigration officials accept affidavits of financial sponsorship from accredited NGOs that could assure private assistance to refugees. The use of private agencies mobilized civilian resources in new way that allowed tens of thousands of impoverished Jews to enter the U.S. before 1939 without private sponsors and without an added burden on public welfare.

Warren’s memorandum opened the gates for a public-private partnership that Porter sees as the centerpiece of U.S. refugee resettlement programs in the 20th century. Proceeding chronologically, Porter places refugee aid into what historians have identified as the “increasingly public, hierarchical, and institutionalized” development of humanitarian policy.

At the onset of the Second World War in 1939, a flurry of new relief organizations created widespread duplication, confusion, and waste. What distinguished the “NGO revolution” of WWII from the similar cacophony of private relief campaigns during WWI, however, was the supervisory role taken on by the U.S. government. By 1944, the United States spearheaded a progenitor to the current United Nations, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA)

Porter applauds the U.S. government’s ability to produce “a profoundly more effective and rationalized field of international relief” by the end of WWII. But while centralization reduced redundancy, it also created a bevy of issues; historians, therefore, tend to balance the technical accomplishments of UNRRA alongside its massive failures in the arena of international politics.

|

| Protestors against the U.S. Trump administration voice their commitment to the world's dispossessed. |

While acknowledging the controversy over forced repatriation of displaced persons (DPs) in Europe, an action many consider UNRRA’s greatest political blunder, Porter picks up the story of DP resettlement after the majority of European DPs had already boarded trains to uncertain futures in their former homelands. Instead he follows the discrepancy between intention and outcome for a “residual” population of DPs who had avoided repatriation and in 1948 set out for new homes abroad.

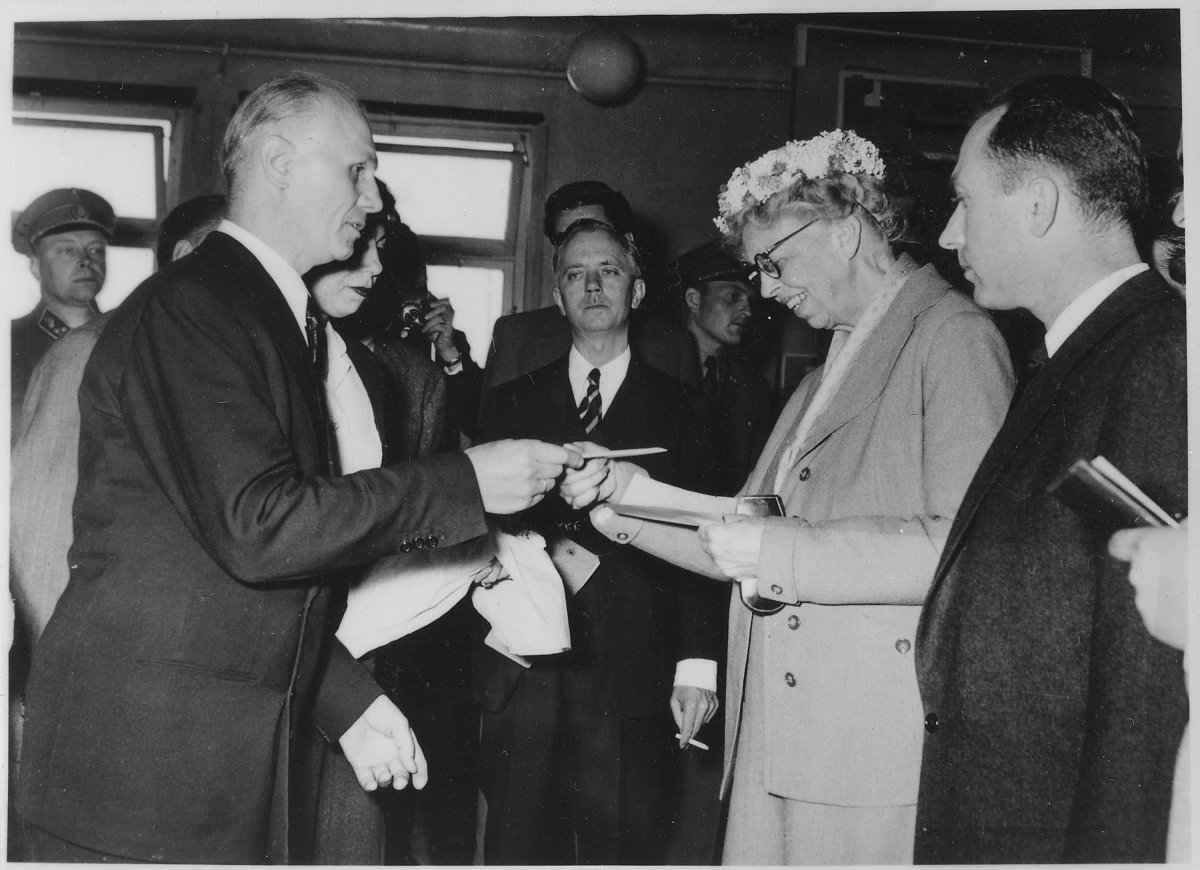

The U.S. welcomed Europe’s DPs, projecting the image of a benevolent global power offering a better life, but domestic realities often undercut American rhetoric and even played into Soviet propaganda. Porter demonstrates that the United States labor market into which DPs arrived could equally “reward and exploit” those who had hoped to achieve the American dream. Porter shows this was also true of Hungarian political refugees who arrived after a failed 1956 anti-Soviet uprising just in time for an economic recession. After the initial enthusiasm to welcome so-called Hungarian “Freedom Fighters” into the U.S. had waned, many Hungarians found themselves in poor economic circumstances, wishing to return home.

|

| Eleanor Roosevelt visits Hungarian Freedom Fighters in Salzburg, Austria, 1957. |

Perhaps the most significant contribution of Porter’s work comes from his juxtaposition of national and racial identity in the U.S. throughout the 20th century. Well-documented chapters explain how Latvian DPs found themselves embroiled in the racial and economic tensions of America’s Jim Crow south, and how the haphazard work of an overburdened private agency resulted in the enrollment of a Hungarian student at an all-black university in South Carolina. The final two chapters extend the question of race and refugee welfare to the first waves of non-Europeans to flee to the U.S.—Cubans fleeing the ascent of Castro in 1959 and Indochinese in the wake of the Vietnam War.

The rise in the number of non-European refugees also came with a shift in federal involvement. Beginning with Cuban refugees in Miami, the federal government began to incentivize refugee resettlement outside of Miami and to subsidize refugee welfare. An insightful epilogue examines the continued application of federal aid to increasingly global and diverse populations.

By the 1980s, however, resentment toward public welfare came to include criticism of refugees on federal funds. Porter extends his analysis to the Obama administration, showing that the Great Recession of 2008, the rise of the so-called Islamic State, and even attacks such as those in San Bernardino in 2015 created obstacles to solidarity with non-European refugees.

But federal commitments to refugees have always been tenuous, and Porter notes that the 1.6 billion dollar budget in 2015 for federal refugee programs amounts to only one tenth of what cities and private agencies contribute. In a time when many question the efficacy of the federal government, it is perhaps important to underscore the importance of local initiatives in both broadening and deepening America’s solidarity with the world’s dispossessed.

Porter’s focus on the admission of refugees into the United States necessarily leaves more to say about the refugee work of other international actors, such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and also leaves out other American humanitarian endeavors as tools of international soft power, especially in matters of global health and food security.

Overall, however, Porter offers a concise and well-argued presentation of refugee aid as part of U.S. humanitarian policy. He both astutely synthesizes existing scholarship on American humanitarianism and adds valuable depth in exploring the connection between domestic economic and social relations alongside notions of international responsibility.