Writing in Slate in the early days of the Great Pandemic, Daniel Sarewitz suggested that COVID-19’s challenges to American life were likely to dissolve the deeply-embedded suspicions of science in the United States. A prominent voice on the intersection of science and public policy, Sarewitz contended that in contrast to most other pressing issues on which science had a primary voice—climate change or environmental poisoning, for instance—COVID-19 was compelling “people everywhere . . . to put their immediate interests and conflicting values aside in the service of achieving a much larger, shared goal of slowing the pandemic.”

People would see expertise in motion, he presumed, as clear “chains of causation” bolstered public confidence. Ideological agendas would shrivel as national unity took hold. “For this crisis, the things that unite us are outranking those that divide us,” he wrote. “Pandering and opportunism . . . are being brought to heel by the pincer combination of shared values and facts on the ground” (Slate, March 24, 2020).

Now a year later, Sarewitz’s expectations seem absurd. Frequent exhortations to “Follow the Science” and its common variation, “Trust the Science,” became not rallying cries but tag-lines in the culture war.

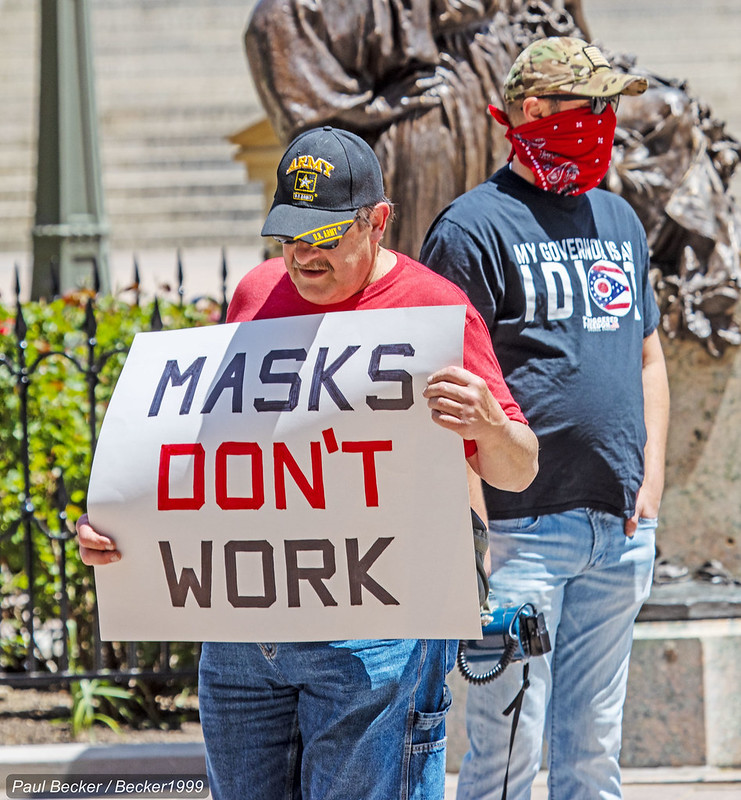

The anti-science crowd ridiculed mask-wearers as sheep mindlessly following the herd. Armed crowds gathered at the homes of public-health officials across the country and hounded them from their jobs. The good Doctor Fauci came to fear for his family’s life in the face of persistent death threats. Rather than welcoming science as a heroic enterprise, a sizeable swath of Americans regarded it as a totalitarian menace to liberty.

For some, science was an appeal to unreason. Hence the Georgia congresswoman, Marjorie Taylor Green, whose scientific expertise centers on Jewish space-lasers, posted a call outside her office to “Trust the Science!” that apparently proves that there are only two genders. No wonder Sarewitz concedes that his March 2020 essay was “the dumbest thing I ever wrote.”

A protestor in Ohio expresses anti-masking sentiments, May, 2020. (Image by Paul Becker).

As Andrew Jewett makes clear in his new book, Science Under Fire, the scientific enterprise in America has long drawn public hostility. A companion to his earlier book, Science, Democracy, and the American University (2012), Jewett’s new study follows nearly a century of critiques of scientific cultural authority, from the 1920s to roughly the present.

Rooted in the gradual nineteenth-century secularization of knowledge, this long debate was never so much about scientists or science as a useful enterprise. The critics’ enemy was not science but “scientism,” a word invented in the mid-twentieth century to describe the conceit that science could shape human behavior.

Jewett argues that those who objected to the growing authority of science took issue with the application of what they regarded as the “materialistic approach . . . to the study of human beings.” Science’s cold rationality could never speak to the mysteries of the soul, critics maintained, and was therefore incapable of guiding people to lives well led or defending individual moral freedom.

Students working in a science laboratory at the University of Iowa, ca. 1920.

Having defined their nemesis, Jewett’s subjects took particular aim at social science, which not only trespassed across the divide between science and humanism but, worse, laid claim to cultural authority on the grounds of value-neutrality. And that was its worst offense, because inherently science had nothing to say about norms and values.

To Jewett, the battle over scientism was never episodic, even though there were moments when science seemed unnervingly supreme—the atomic moment most obviously. Nor were the critics purely religious or ideologically exclusive thinkers. Jewett is less interested in dogmatists than in those who wrestled squarely with modernity’s implications for morality and human subjectivity.

Modernity left people in an indefinite state. The physical sciences disabused them of comforting religious myths but offered nothing more than mechanistic guides on how to live. While some religious thinkers, practicing scientists among them, did attempt to work through this limbo, others, such as Irving Babbitt and Joseph Wood Krutch in the 1920s, looked to a humanism rooted in art and literature to create a moral framework that “represented a reasoned deference to the sifted wisdom of the ages, not a slavish devotion to tradition.”

In part because the critique rested on philosophical and moral abstractions conveyed in “capacious language,” an eclectic collection of thinkers, from the prominent to the obscure, sustained “a complex set of . . . alliances that have structured much of American intellectual life, and a good deal of American politics, since WWII.”

Anti-New Deal relief protest sign near Davenport, Iowa, 1940.

For Jewett, the debate has been a constant since WWI. Instead of waxing and waning, it has recirculated through different historical moments. Rather than understanding the New Deal as an exercise in democratic collectivism, these critics saw it as an attempt at social engineering based on William Ogburn’s “cultural lag” theory. In this regard, the New Deal was cousin to totalitarianism, with its value-free reduction of people into mindless automata. Nazism made it clearer than ever that scientism destroyed moral reasoning.

Nazism’s defeat brought no respite, because the early postwar period was the heyday of scientism, with the social sciences at the height of their prestige and rationalistic Cold War liberalism solidly in command of culture and state.

“There was something for everyone to fear in postwar American science,” Jewett writes, from the Bomb to the barren rationalism of the Organization Man. Some enemies clarified the stakes more than others, particularly Talcott Parsons with his dry functionalism and B.F. Skinner with his outrageous behavioralism.

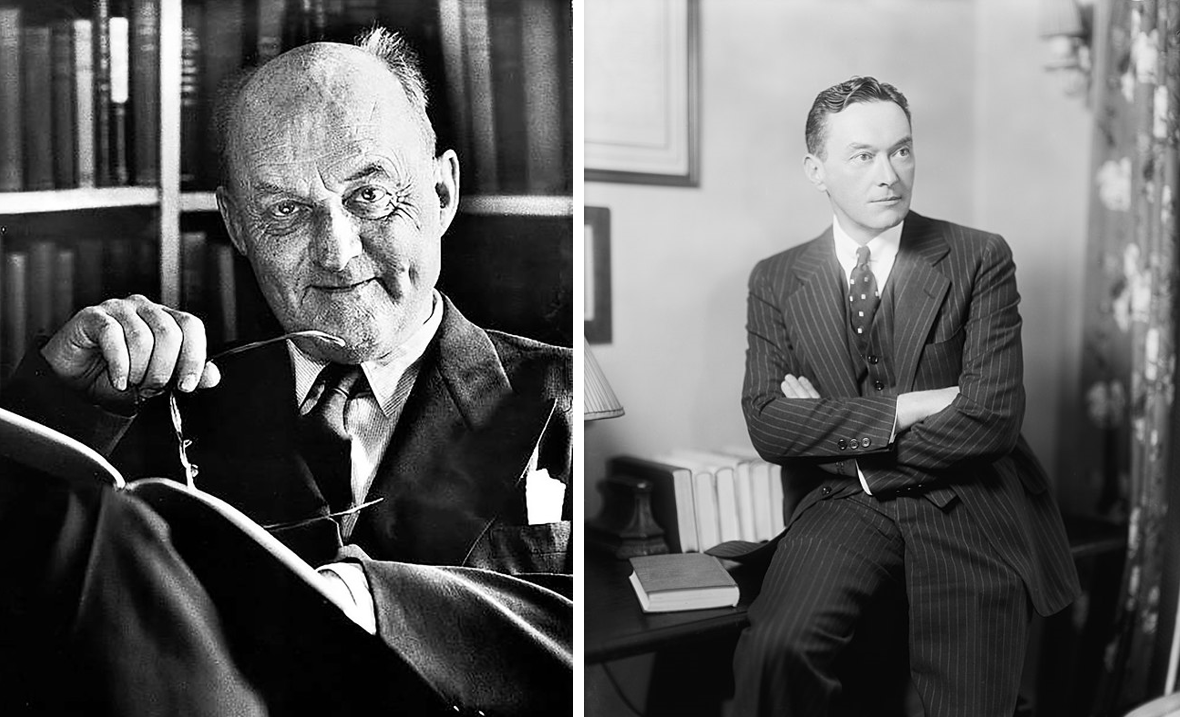

Reinhold Niebuhr pictured in 1956 (left). Walter Lippman in 1920 (right).

In part because some of the same figures were at work—Walter Lippmann, Reinhold Niebuhr, Joseph Wood Krutch—the attacks on postwar social science mostly rehashed old arguments until the New Left and New Right rejuvenated them.

To Jewett, the main intellectual and cultural thrust of the Sixties was a repudiation of the postwar hold of scientism, whether in Russell Kirk’s insistence on its amorality, student radicals’ insistence that the scientific mentality served the military-industrial system, or Theodore Roszak’s counter-cultural supplantation of rationality.

Given the moment we are in, Science Under Fire seems particularly well timed, and it ought to be instructive. But the book does not offer quick counsel. For one thing, it is so closely tied to Jewett’s earlier work that it has to be understood as part of a long intellectual enterprise. It could not have been his intention to engage the present at length, and the question that he has pursued reaches much farther: How does a society profoundly dependent on the products of scientific practice hold the practitioners and promoters to democratic account?

Jewett’s answer is entirely sensible and not without its cogency for our present fix. He calls on us to tone down the accusations and clarify the abstractions that are volleyed back and forth between the critics and defenders of science; the latter should concede their own limitations, and the former see science for what it is—“a thoroughly human practice . . . that produces remarkable outcomes” (264). Where science and the public good meet, some form of citizen involvement in high-stakes practices should be developed.

Such an equilibrium might have been possible when the critics of science were serious humanists, as most of Jewett’s subjects were. But it is difficult to be optimistic now when the noisiest critics wallow in sociopathic ignorance.

Yet public support for science is remarkably high: 86% of Pew respondents to a 2020 poll said they trusted scientists to act in the public interest. Maybe we should see the COVID-19 vaccination campaign as a grand experiment in democratic participation. At the end of it, both Andrew Jewett and Daniel Sarewitz might seem prescient.