In 2019, John Bolton, briefly National Security Advisor to President Donald Trump, said when asked about the U.S. administration’s vocal support for the beleaguered opposition to the Venezuelan government, “The Monroe Doctrine is alive and well, it’s our hemisphere.”

Bolton’s quote is the point of departure for Britta and Russell Crandall's survey of the nearly two and half centuries of the United States’ foreign relations with Latin America. The book aims to question the interpretation of a monolithic, imperial agenda as the driver of U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America. The authors argue that while sometimes the actions of U.S. policymakers showed they believed Latin America was part of “our hemisphere” in the possessive sense, at other times officials recognized a shared, collective sense of “our hemisphere.”

The volume, a study of how and why U.S. officials exercised power in Latin America, reflects the authors’ backgrounds in both the academic study of foreign policy and its practical application. In addition to their posts as professors of international politics and American foreign policy at Davidson College, they have held official appointments within the executive branch of the U.S. government.

But despite their past bureaucratic posts, the Crandalls aim for a balanced account, not an apologia for the actions of the United States. In doing so, the authors mostly synthesize secondary sources, including much of their own previous work.

Throughout the history of U.S. relations with Latin America, the Crandalls see both ideals and interests in U.S. policy. In the nineteenth century, officials sometimes demonstrated a broad commitment to republican and democratic principles.

For example, as revolution swept across the Spanish colonies, not only Presidents and Secretaries of State but also newspapermen and common citizens effused sympathy for the revolutionaries’ cries of liberty. Yet in other instances, policymakers’ professions of freedom and democracy were expedients to cover instances in which they desired—or circumstances forced them—to act in hard-headed national interest.

The Crandalls’ interpretation of the Mexican-American War is illustrative of their attempt at a balanced and contextualized narrative. While highlighting the mendacity of the pretext for the war against Mexico, they point to fluid international borders, weak state authority, restive populations, and reactive, equivocal actions by policymakers as precipitants of the conflict.

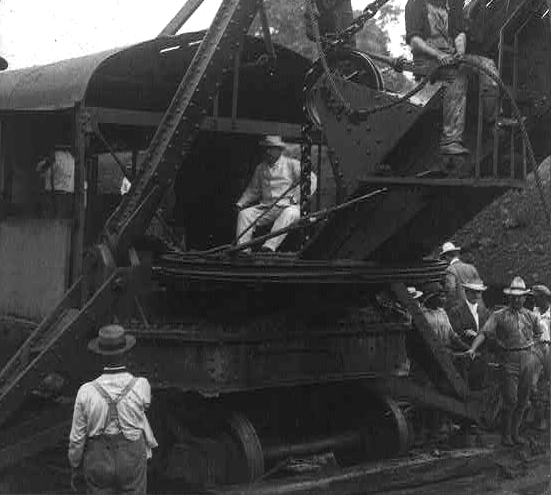

The Crandalls’ narrative of the United States’ early twentieth-century interventions in the Caribbean Basin follows a traditional state-centered approach. They apply Samuel Flagg Bemis’ concept of “protective imperialism” to episodes where U.S. administrations used their preponderance of power to impose humiliating trusteeships, exclude foreign powers, and suppress rebellion.

While seeing protective imperialism as a useful interpretive lens, they eschew the distinguished mid-twentieth century historian’s dismissal of the period as a harmless historical aberration in an otherwise healthy hemispheric relationship. At the same time, they evince some of Bemis’ sentiment in their explanations. Sometimes various interventions were mistakes, but mistakes made in over-zealous pursuit of admirable ideals (like Woodrow Wilson’s foray into Mexico).

Other times, those who stood to gain the most from the use of force, such as powerful businessmen, were ambivalent about intervention. Such explanations do slant toward apologies, despite the authors’ efforts to be objective. But unlike Bemis, it is not nationalism that blinkers the Crandalls’ account from the toll of the various interventions. Instead, the myopia comes from soft-pedaling explanations such as racism, toxic masculinity writ large, or economic exploitation that historians have offered in the many decades since Bemis’ work was prominent.

The authors point to national security and political realism in explaining heavy-handed U.S. actions in Latin America during the Cold War. The United States, they show, acted as a hemispheric hegemon when it overthrew Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz, opposed the Cuban Revolution, intervened in the Dominican Republic, destabilized Salvador Allende’s Chilean government, and involved itself in the Central American civil wars of the 1980s.

While their depiction of U.S. power is clear-eyed, they mostly avoid discussing the consequences of it for the various nations in which it was exercised. They offer little about the long-term political, social, or economic consequences for those nations, nor do they explain what that exercise of power meant for the historical evolution of the United States itself.

Whereas the book covers well-trodden historical ground through the end of the Cold War, the final part provides needed coverage of the three decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Their answer to the question of whether the United States became more or less controlling in Latin America as a result of its standing as the sole remaining superpower is both – but in different ways.

It has become more interventionist in the war on drugs, going “supply side” by pressing narcotic-producing nations like Peru, Colombia, and Bolivia to adopt policies and accept U.S. military and law enforcement presence to eradicate coca production. But it also intervened in the interest of democratic institutions, sending troops to Haiti to both uphold the democratic election of Jean-Bertrand Aristide and, the following decade, to keep him out of power.

Neoliberalism, in the authors’ estimation, was less a symptom of U.S. hegemony and more a short-lived episode of hemispheric cooperation that eventually foundered on the rocks of nationalism. Finally, distracted by its wars in the Middle East, Washington reverted to its traditional inclination to neglect the region, leaving Latin American nations with greater geopolitical latitude than they possessed prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The Crandalls do not venture far outside the realm of official policymaking in their history. While a book with the subtitle The United States in Latin America could allow many different historical actors to take center stage, the authors demonstrate that in their narrative, the “United States” refers to the United States government.

Social groups, both national and transnational, remain in the background. The reader learns little of the effect on Latin American societies of U.S. capital flows into Latin America in search of markets and raw materials. Likewise, readers wanting a discussion of the cultural hegemony exercised by the northerners over their Latin American neighbors will be dissatisfied.

The way U.S. money, pop cultural exports, and the like shaped Latin American social, familial, and gender norms—and how Latin Americans negotiated those influences—does not factor into the narrative.

Overall, the volume’s 42 short, episodic chapters convey a certain ambiguity about the consequences and meaning of U.S. power in the Western Hemisphere. The Crandalls avoid a defined interpretive framework—such as nationalism, dependency, world systems and the like—in their explanation of events. Some may be impatient with their “explain, don’t justify” approach to historical objectivity. But undergraduates being exposed to the history for the first time will benefit from the Crandalls’ intention to avoid anachronistic moral standards and to encourage readers to make up their minds for themselves.