According to Thomas Jefferson, the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution built a “wall of separation” between church and state. But that doesn't mean politicians haven't brought religion into politics. In this essay, historian Daniel Williams details how both liberal and conservative politicians have used Christianity to further their agendas.

In view of the decades-long close alliance between the Christian Right and the Republican Party, it may not have been a surprise when President Donald J. Trump established a White House Faith Office in February 2025 to “assist faith-based entities, community organizations, and houses of worship in their efforts to strengthen American families” and entrusted its oversight to his favorite television evangelist, Paula White-Cain.

After all, the GOP’s courtship of Christian voters has sometimes been so overt that some have suggested that the “Grand Old Party’s” acronym should stand for “God’s Own Party.”

But what may be more surprising is that the Democratic Party and the American progressive movement have also been just as strongly influenced by Christianity.

From William Jennings Bryan’s “cross of gold” speech at the 1896 Democratic national convention to President Joe Biden’s frequent invocation of principles from his Catholic faith, Democratic politicians have quoted scripture, appealed to the moral teachings of Jesus, and brought their campaigns to the nation’s churches, just as Republicans have.

It turns out that both political parties have long identified God as a strong ally. But this alliance doesn’t mean that Republicans and Democrats think of God or religion in the same way.

Instead, the two parties have been drawn to different sets of Christian principles and have appealed to very different Christian constituencies. If we understand those differences, we’ll be better equipped to understand the religious origins of our contemporary partisan polarization.

Religious Influences on the Origins of the Democratic and Republican Parties

Although the First Amendment prohibits government “establishment of religion,” it does not restrict religious influence in politics.

Unlike Britain, the United States would never have an established church. Unlike France, on the other hand, American political leaders have always felt free to invoke religious principles and direct references to God and scripture in their public addresses, often projecting a close association between religion, morality, and public virtue.

In George Washington’s Farewell Address, he said that “religion and morality are indispensable supports” of “political prosperity,” and that there was no reason to believe that “national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

As America’s two-party system emerged, partisans on both sides invoked religion to argue that their party was better positioned than the other to protect the nation’s morality.

In the election of 1800, New England Congregationalist ministers who supported John Adams warned about Thomas Jefferson’s religious skepticism, while evangelical Baptists who supported Jefferson portrayed him as a champion of religious liberty whose policies would benefit their fellow Baptists and allow voluntaristic evangelical religion to flourish.

A few months after Jefferson’s inauguration, the Massachusetts Baptist minister John Leland traveled to the White House to give a 1,235-pound “mammoth cheese” to the new president as a token of appreciation from his Baptist congregation.

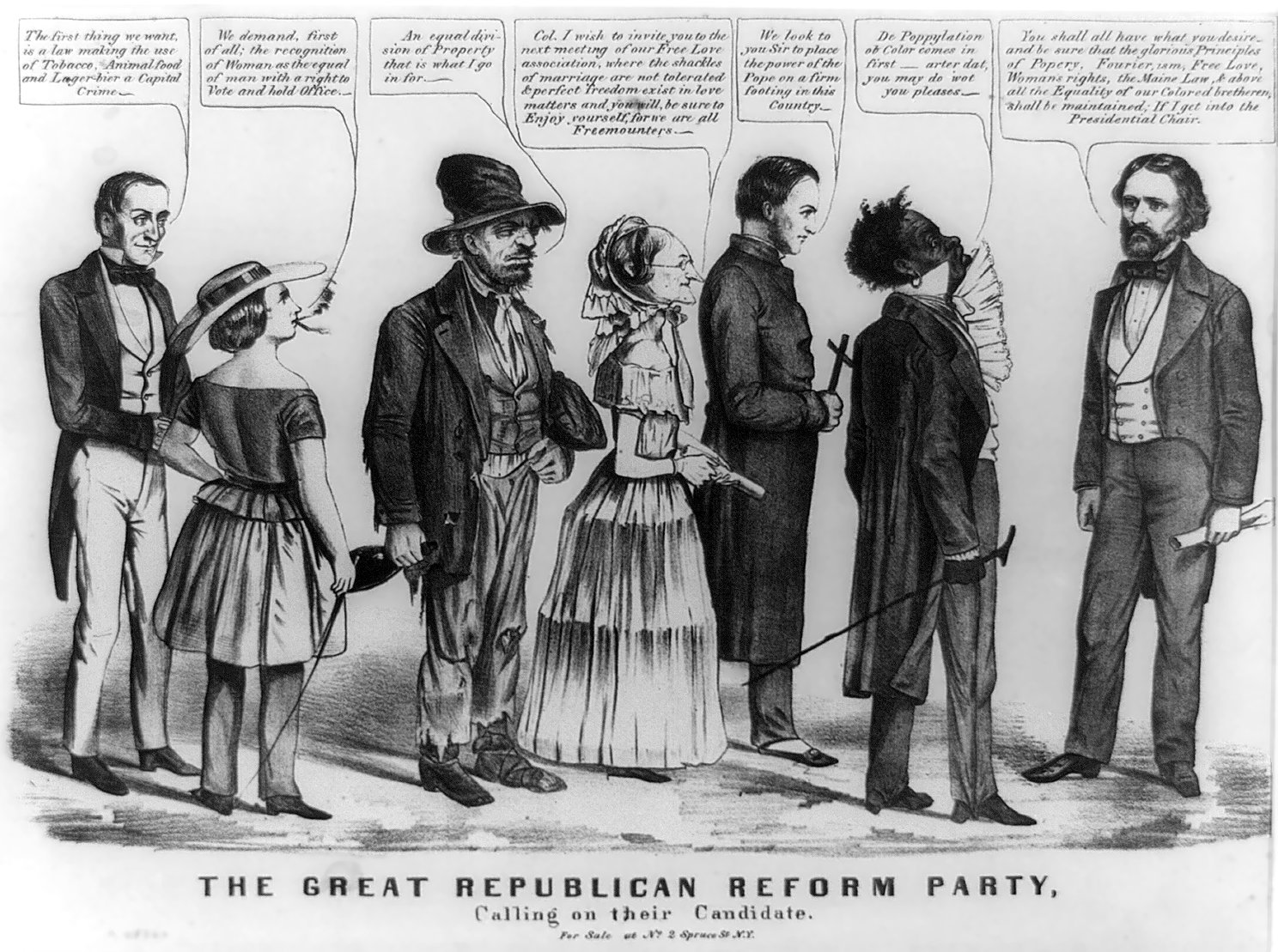

When the modern Republican and Democratic parties emerged later in the 19th century, this partisan division between Protestant moralists and low-church evangelicals continued.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, the Democratic Party, though often wary of too close a connection between church and state, had a strong appeal to working-class Christians, including Scots-Irish Presbyterians on the southern and western frontier, Baptists who believed strongly in religious liberty, and Irish Catholic immigrants who resented the Protestant moralism of the Republicans.

The Republican Party, by contrast, appealed to Protestants—including Bible-believing evangelicals, high church Episcopalians, and skeptical Unitarians who may have doubted the deity of Jesus but who were filled with moral fervor when it came to the issue of slavery.

What united this disparate group of Protestants was not only a conviction that slavery was wrong and that its territorial expansion needed to be stopped but also a belief that religion-based moral regulation in general was a good thing.

The 1856 Republican Party platform called for federal legislation against polygamy in the territories—a promise that Republicans acted on by passing the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act in 1862. Many Republicans also supported the temperance movement and other calls for Protestant-inspired moral regulation.

The 1888 Republican Party platform declared, “The first concern of all good government is the virtue and sobriety of the people and the purity of their homes. The Republican Party cordially sympathizes with all wise and well-directed efforts for the promotion of temperance and morality.”

Although appeals to Christian moral principles might have been more overt in the Republican party platform than in the Democratic one, Christians in the Democratic Party insisted that Republicans did not have a monopoly on Christian morality.

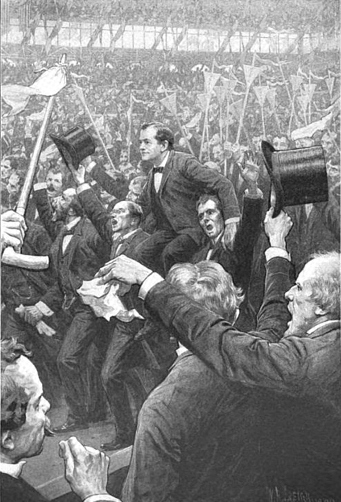

In 1896, the party nominated as its presidential standard-bearer the devout Presbyterian William Jennings Bryan, who frequently portrayed his fight against the eastern banking establishment and the gold standard as a holy campaign grounded in Christian egalitarian principles of concern for the common person. “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns,” he told the Democratic national convention in an invocation of the images of Jesus’s crucifixion. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

A few Democrats were also influenced by the Social Gospel movement, a liberal Protestant campaign that had particular appeal for Progressive Republicans but that also shaped the political vision of some Progressive Democrats, including President Woodrow Wilson.

In the late nineteenth century, progressive Protestant ministers such as Walter Rauschenbusch in New York and Washington Gladden in Ohio had begun advocating for workers’ rights and social reform in the name of Christianity—a theology that quickly became known as the “Social Gospel.”

The Federal Council of Churches (a coalition of mainline Protestant denominations) followed suit by issuing a “Social Creed” in 1908 that called for a “living wage” and the “abolition of child labor.”

In 1919, the nation’s Catholic bishops launched the National Catholic Welfare Council, which called for many of the same social principles—especially the living wage.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt began championing some of these measures in the 1930s, both liberal Protestants and Catholics endorsed the New Deal as an application of the Christian principles they had already been advocating.

During Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s, what had been a general evangelical-inspired Democratic Party concern for the “common man” transformed into a more explicit commitment to the principles of the Social Gospel.

Roosevelt welcomed this support and echoed church leaders in portraying the New Deal as an application of Christian teaching. “We call what we have been doing ‘human security’ and ‘social justice,’” he told a group of Protestant ministers in 1938. “In the last analysis all of these terms can be described by one word, and that is ‘Christianity.’”

Like Bryan, FDR invoked biblical imagery and scenes from the life of Jesus to excoriate the rich. Although he had been raised in a wealthy home and was not necessarily a model of piety in his personal life, he was a liberal Episcopalian who was shaped by the Social Gospel of the era, and he accepted the Social Gospel’s view of Jesus as a prophet of the downtrodden.

In keeping with that view, he drew on scenes from the gospels to portray his own New Deal measures in righteous terms. “The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization,” he said in his inaugural address of 1933. “We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than monetary profit.”

During the early years of the Cold War, both the Democratic president Harry Truman and the Republican president Dwight Eisenhower portrayed America’s fight against international communism as a defense of Christian values and a battle for religious freedom. Both suggested that the nation’s tradition of human rights had to be grounded in a Judeo-Christian religious framework.

“We believe that all men are created equal because they are created in the image of God,” Truman declared in his inaugural address of 1949, in a phrasing that combined the biblical creation narrative with a line from the Declaration of Independence. “From this faith we will not be moved.”

He concluded his inaugural with a call to extend the recognition of God-given freedom and dignity to the rest of the world: “Steadfast in our faith in the Almighty, we will advance toward a world where man’s freedom is secure. To that end we will devote our strength, our resources, and our firmness of resolve. With God’s help, the future of mankind will be assured in a world of justice, harmony, and peace.”

Eisenhower said much the same in his own inaugural address four years later.

After reminding his audience that new scientific developments had given people the power to annihilate the entire human race, he suggested that religious faith in a transcendent God and an unchanging set of moral principles grounded on a belief in human dignity was the only safeguard against global destruction.

“At such a time in history, we who are free must proclaim anew our faith,” Eisenhower said. “This faith is the abiding creed of our fathers. It is our faith in the deathless dignity of man, governed by eternal moral and natural laws. This faith defines our full view of life. It establishes, beyond debate, those gifts of the Creator that are man's inalienable rights, and that make all men equal in His sight.”

Both Republicans and Democrats of the early Cold War era agreed: America’s tradition of democracy and human rights could be sustained only through faith in the transcendent God of Christianity, Judaism, and the Bible. The God of the Bible was thus America’s God.

And though the two parties emphasized slightly different principles when appealing to this religious tradition—with the Democratic party more likely to emphasize the Social Gospel tradition that appealed to liberal Protestants and Catholics and the Republican Party more likely to emphasize the GOP’s longstanding grounding in Protestant moralism—the two parties were united in their adherence to a Judeo-Christian, biblically based framework for understanding the nation’s human rights tradition and its opposition to international communism.

The Religious Divergence of the Two Parties

The civil rights movement and the Vietnam War disrupted this bipartisan religious comity. For many younger Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, Martin Luther King Jr’s excoriations of white religious apathy toward racial justice exposed the hypocrisy of liberal religious leaders’ championship of democracy.

If human rights and democracy were the ultimate priorities of Christian ethics, why were religious and political leaders who publicly championed democracy so tepid in their support for the rights of people of color? Why was the white church of the South quiet (or even resistant) in the face of the civil rights movement? Why was the U.S. government in the 1960s waging a war in Vietnam that involved napalm attacks on Vietnamese civilians?

A younger generation of liberal ministers became radicalized by the civil rights movement and antiwar protests and began seeing their primary task as prophetic—that is, “speaking truth to power.”

In doing so, they began to critique “Christian America” as hypocritical, which meant that preserving the nation’s religious heritage was less important than calling the nation to honor its commitment to equality and democracy. And if that was the case, their closest political allies might well be nonreligious people who shared their values (but not their faith) rather than fellow Christians who shared their faith but not their values.

Under the influence of a younger generation that embraced this pluralist vision, the Democratic Party of the 1970s placed less emphasis on public affirmations of Christian faith and more emphasis on the moral values of equality and social justice. No longer did national Democratic politicians echo the words of Harry Truman and ground calls for freedom in a “steadfast faith” in “the Almighty.”

But this abandonment of a triumphal endorsement of Christian theism as a national faith was not necessarily a sign that the party was fully secularizing. Instead, the party’s presidential nominees were deeply shaped by Christianity and, in particular, by the Social Gospel’s emphasis on love for one’s neighbor.

The Democratic presidential nominee of 1972, George McGovern, was a Methodist minister’s son who quoted from the Sermon on the Mount on the campaign trail. His running mate, Sargent Shriver, was a devout Catholic whose faith had been a central motivation for his work in the War on Poverty.

The 1976 Democratic presidential nominee was Jimmy Carter, a Southern Baptist deacon and Sunday school teacher who was the first major-party presidential candidate to publicly say that he had been “born again.” Carter’s running mate, Walter Mondale, was another Methodist minister’s son steeped in the values of midwestern liberal Protestantism.

In the 1990s, the Democrats nominated two Southern Baptists, Bill Clinton and Al Gore, both of whom were frequent churchgoers. Gore, in fact, had studied at Vanderbilt Divinity School.

And though the Democratic Party had the reputation of being a secular party in the early 21st century, its presidential nominees frequently spoke of how deeply shaped they had been by their faith experiences.

John Kerry was a lifelong Catholic who had served as an altar boy. Barack Obama wrote about his conversion experience in an African American church in Chicago, and he welcomed opportunities to speak at churches and other Christian venues about the place of faith in public life. Hillary Clinton was a lifelong Methodist who attributed her concern for the poor to her Methodist faith and the New Testament epistle of James. Joe Biden attended Mass every week and frequently spoke about his Catholic values.

In a sign of how commonplace references to scripture and the tenets of the Social Gospel were in the party, even Bernie Sanders, a nonreligious Jew, made a campaign stop at Liberty University during his bid for his party’s 2020 presidential nomination and gave a speech that referenced Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount and other scriptural passages in support of his economic policy positions.

All of these presidential candidates frequently spoke at Black churches, where the connections among Christian faith, social justice advocacy, and Democratic party politics were long established. Indeed, African Americans who were members of historically Black denominations were more likely to identify as Democrats than African Americans who were not.

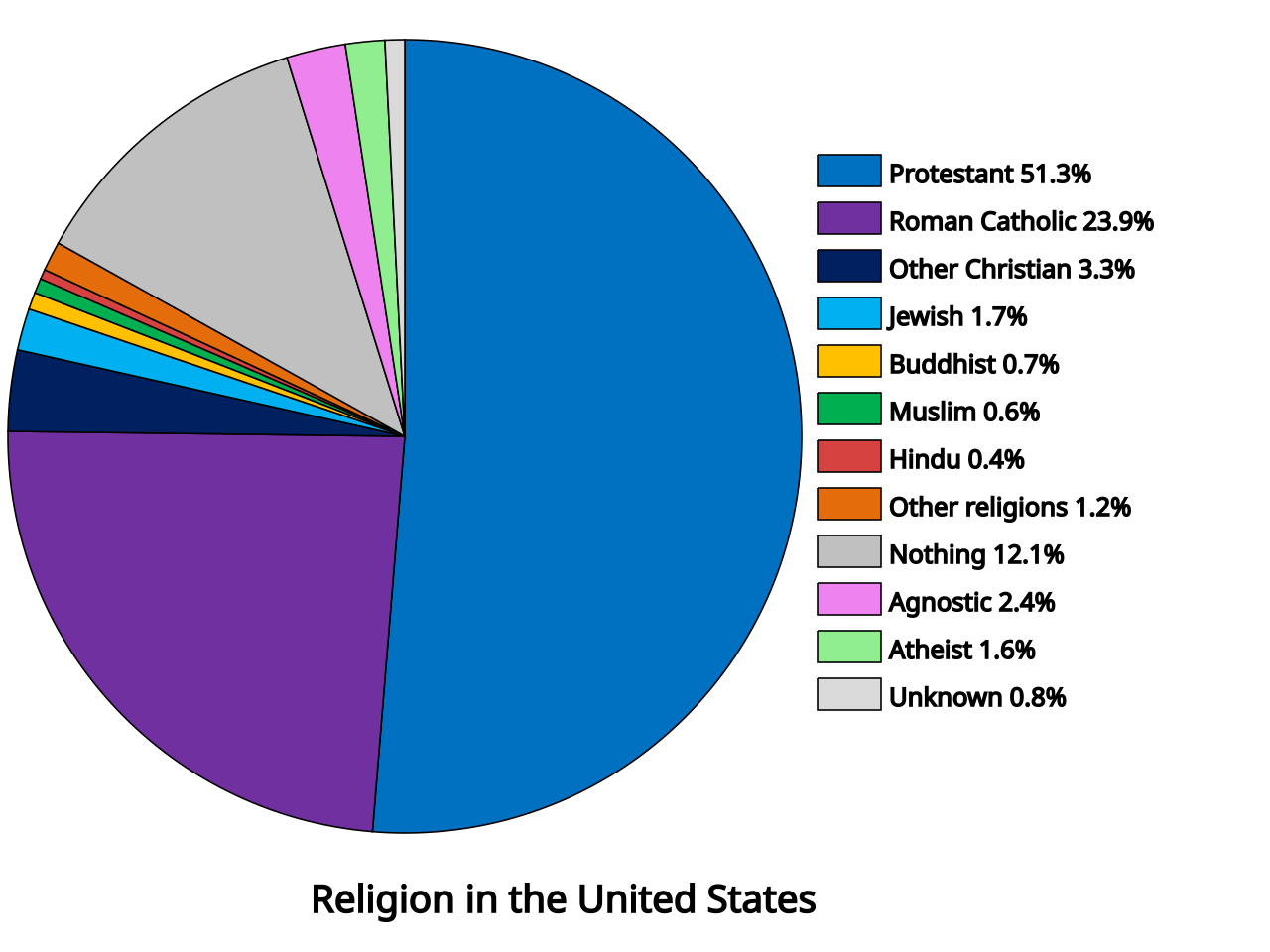

But in spite of the Democratic Party’s alliances with Christian churches, it acquired a reputation as a secular party partly because of the disproportionately high number of “nones” who identified as Democrats and partly because of its opposition to the Christian Right’s social causes—especially on the issues of abortion and sexuality.

If the Democratic Party’s recent approach to religion was shaped by the civil rights movement’s emphasis on pluralism and rights consciousness, the Republican Party’s contemporary religious ethos has been shaped by a conservative Christian reaction to another movement of the 1960s—the sexual revolution.

Conservative evangelicals and Catholics who opposed the liberalization of American sexual mores in the late 20th century pushed the GOP to take more conservative stances on abortion, gay rights, and other policy matters that they argued were an attack on the traditional family.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as abortion and second-wave feminism were becoming national political issues, it was not yet clear which party (if any) would oppose abortion rights and which would support them. In the years immediately before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion nationwide, more Republican governors than Democratic ones signed into law abortion legalization bills.

On the national level, some conservative Republicans, such as Senator Barry Goldwater (R-AZ), supported abortion legalization on libertarian grounds, as did most of the party’s liberal wing—including the most prominent liberal Republican, New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, who signed into law the nation’s most liberal state abortion policy before Roe v. Wade.

And among Democrats, many Catholics—along with a few Protestants—opposed abortion. Both Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) and civil rights advocate Jesse Jackson opposed abortion legalization for at least a few years in the 1970s.

But even though the Republican Party of the 1970s had many supporters of abortion rights—and even though the party leadership included self-identified feminists who were proud of the party’s endorsement of the Equal Rights Amendment—the GOP had also long identified itself with Protestant moral causes and a generic endorsement of Christianity in public life. That religious tradition made the party a natural home for conservative evangelicals.

In the 1950s, Eisenhower’s endorsements of religious faith in the context of the Cold War built on this tradition. In the early 1970s, Richard Nixon’s White House church services and denunciations of the permissiveness of the counterculture likewise appealed to socially conservative white Christians who wanted to see a fusion of moral order and public endorsements of religion.

Nixon’s own moral failings disappointed some of his Christian supporters but did little to diminish their desire for a president who would restore a Christian-based moral order in the nation and rid the nation of its drug abuse problem, its acceptance of pornography, and its permissive abortion policies.

Some conservative evangelicals hoped that Jimmy Carter, a fellow evangelical Christian, would deliver on their agenda, but Carter was too strongly committed to pluralism to show any interest in restoring classroom prayer to public schools or banning abortion. And if Carter, a devout Baptist, was not interested in violating the principle of pluralism in order to advance a Christian sectarian agenda, neither was the Democratic Party.

Evangelicals found a more receptive audience in Ronald Reagan, whose philosophy of “peace through strength” echoed their own strong anticommunism and whose conservative philosophy of limited government was compatible with their antipathy to an “activist” Supreme Court that had used its power to restrict school prayer and expand abortion rights.

In addition, the longstanding Republican endorsement of a Protestant-based moral order—vestiges of which still appeared in late-20th-century policies as Nixon and Reagan’s support for a war on drugs—made the GOP a natural home for the Christian Right that evangelical Protestants helped to create in the late 1970s.

Until the late 20th century, the Republican Party’s Protestant support had arguably come more from mainline Protestants than from evangelicals—though there were plenty of evangelicals in the years before Reagan’s presidency who also supported the GOP, as Billy Graham’s alliance with Eisenhower and Nixon demonstrated.

But in the 1980s and 1990s, as mainline Protestantism’s membership and corresponding political influence began to decline—and as evangelicalism continued to grow—evangelical support for the GOP became more noticeable, and the predominant Protestant influence in the Republican Party shifted from mainline Protestantism to evangelicalism.

This evangelical influence on the GOP also correlated with a geographic shift in the party, because while mainline Protestants were well represented in the North, evangelicalism was strongest in the Sunbelt and in the conservative regions of the Midwest—regions of the country that had been far from monolithically Republican before the 1970s but that were the key sources of support for both Nixon and Reagan.

By 2008, evangelical Protestants accounted for 40 percent of Republican voters. When combined with their conservative Catholic allies, they exercised a controlling interest in the party.

They used this power to wage a culture war against abortion and gay rights, both of which became fault lines in American partisan politics.

While many Democratic politicians in the late 20th and early 21st centuries were personally opposed to abortion (and, for a while at least, same-sex marriage or other LGBTQ+ rights measures) on moral grounds, most endorsed the party’s liberal stances on these issues as an extension of the party’s commitment to pluralism.

Most progressive churches did the same. Progressive Christians also argued that the Democratic Party’s endorsement of universal healthcare and an expanded social safety net accorded well with biblical injunctions to care for the poor.

But conservative Christians believed that the Democratic Party’s policies threatened the family, public morality, and, in the case of abortion, human life.

And because mainline Protestantism was rapidly shrinking in the late 20th and early 21st centuries while conservative Christianity was not, the Religious Right eclipsed the Religious Left in public influence.

And, in turn, the Democratic Party augmented its shrinking Christian constituency with greater appeal to the growing group of nonreligious Americans (or “nones,” as they were often called).

But even if its public image was becoming more secular, the Democratic Party was still deeply shaped by religious values.

And today, as Democrats consider their most likely path back to political power, they may need to draw on their religious heritage once again, just as the GOP is doing. In the next election, we can expect religion to play an influential role in voting decisions—and not only on the side of one political party.

Bratt, James D. A Christian and a Democrat: A Religious Biography of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2019.

Evans, Christopher H. The Social Gospel in American Religion: A History. New York: New York University Press, 2017.

Foster, Gaines M. Moral Reconstruction: Christian Lobbyists and the Federal Legislation of Morality, 1865-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Friedland, Michael B. Lift up Your Voice Like a Trumpet: White Clergy and the Civil Rights and Antiwar Movements, 1954-1973. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Gibbs, Nancy, and Michael Duffy. The Preacher and the Presidents: Billy Graham in the White House. New York: Center Street, 2007.

Harp, Gillis J. Protestants and American Conservatism: A Short History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Inboden, William. Religion and American Foreign Policy, 1945-1960: The Soul of Containment. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Kazin, Michael. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. New York: Knopf, 2006.

Lempke, Mark A. My Brother’s Keeper: George McGovern and Progressive Christianity. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2017.

Marsh, Charles. The Beloved Community: How Faith Shapes Social Justice from the Civil Rights Movement to Today. New York: Basic Books, 2004.

Noll, Mark A., and Luke E. Harlow, ed. Religion and American Politics: From the Colonial Period to the Present. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Zubovich, Gene. Before the Religious Right: Liberal Protestants, Human Rights, and the Polarization of the United States. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022.