Cleaning up America's polluted waters over the last 50 years has been an environmental and public-health triumph. But as historian David Stradling explores this month, the science of water has collided with political debates over the role of government since the early 20th century. He explains how today that collision threatens to pollute our waters all over again.

Donald Trump’s untraditional approach to the presidency has led Politico to call him the “Disruptor in Chief.” Although his disruptions have echoed globally, his own political party might have experienced the most disturbance, as Trump has disregarded some core Republican principles, including free trade and fiscal responsibility.

Environmental Protection Agency scientists in 2009 surveying aquatic life in Newport, Oregon.

In other ways, however, Trump has effectively pressed a traditional Republican agenda, particularly through regulatory rollbacks. Indeed, his administration may represent the apotheosis of the Republican Party’s 50-year movement away from environmental protection through federal regulation.

In fall 2019, the New York Times identified 95 environmental rules the Trump administration had begun rolling back during his first three years in office. More recently, his administration announced a plan to limit the reach of the National Environmental Policy Act, which has required environmental impact statements for federal projects since it became law in 1970.

With this change, Trump promises to speed the approval of infrastructure projects, especially those supporting energy and transportation, and to absolve federally supported projects from considering climate change in assessing environmental impact. Clearly Trump’s regulatory rollback is more than an effort to repeal Barack Obama’s legacy.

The environmental deregulation follows two prominent themes.

The ship, United States Gypsum, hauled coal on Lake Erie from 1940 to 1973 (left). The towboat, Donna York, pushes barges of coal up the Ohio River in 2009 near Louisville, Kentucky (right).

First, his administration has eased natural resource extraction and delivery, especially regarding energy resources: natural gas, oil, and coal.

Second, he has eased or eliminated regulations that impinge on rural property rights, which is to say, he has made it easier for farmers to use their land as they see fit.

Environmental deregulation has thus pleased two important Trump constituencies: the energy sector with its deep pockets and the agricultural sector with its electoral-college votes.

Although the regulatory rollbacks have affected all types of environmental protections, one of the most significant reversed the 2015 Waters of the United States rule, which clarified the meaning of “waters” as pertains to the Clean Water Act of 1972 (and its 1977 and 1987 amendments.)

The Obama-era rule formally defined which “waters of the United States” are subject to federal regulation. The definition included any wetland (PDF File) or stream—any tributary to a larger body of water —that showed physical features of flowing water. Essentially, the rule recognized a fundamental fact about water: it rarely stays put. Wastes discharged into bodies of water tend to wind up in other bodies of water downstream.

The 2015 Waters of the United States rule defined nearly all waters in the nation as subject to federal regulation, ending the confusion caused by the law’s vague language and resultant inconsistent court rulings about its meaning. At least that was the case until fall 2019, when the Trump administration announced it would repeal the rule and replace it with nothing other than the certainty that the EPA would protect a much narrower range of water bodies.

Dramatic and momentous as it appears, this reversal falls squarely within the decades-long debate about the proper role of the federal government in water pollution control.

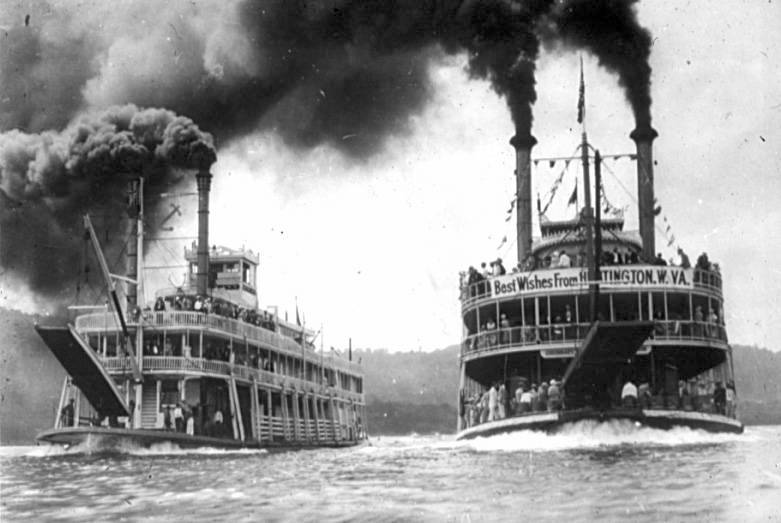

A 1930 race on the Ohio River between two steamboats - Betsy Ann and Tom Green.

From an ecological perspective—the one taken by most scientists and environmental activists—the 2015 definition makes perfect sense. To control water pollution anywhere, you need to control it everywhere, given the connectedness of all water.

From a political perspective, this certainty can appear naïve, if not offensive. Given the constant American debate about the proper role of government, the Waters of the United States rule had been freighted with meaning and consequence, not the least because the rule gave federal employees oversight of casual waters at the edges of farm fields thousands of miles from D.C.

How federal water pollution control authority made its way to wetlands and drainage ditches around agricultural lands—and almost everywhere else in the United States—is a long story involving the work of thousands of activists, scientists, and politicians across many generations and in every corner of the nation.

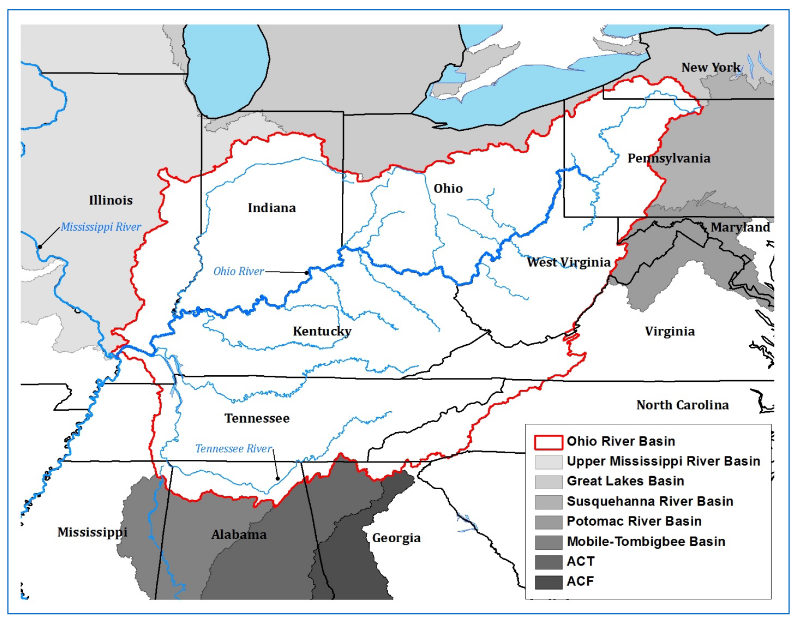

A 2015 map of the Ohio River basin and surrounding interstate-basins.

There were three phases of efforts to clean up our waters across the past 100 years or so. By examining three rivers, all in Ohio, we can see how environmental regulation evolved in the face of growing threats from, and expanding understanding of, the negative consequences of water pollution to both human health and ecological health.

Investing in Sewage Treatment: The Ohio

American cities and industries have always dumped waste directly into waterways with the expectation that currents would remove the unwanted materials, carry them downstream, and dilute them to the point of harmlessness. In a sparsely populated country where industry relied on a limited range of chemicals, this approach generally worked fine—periodic cholera outbreaks notwithstanding.

As the country became more populous and industries more and more reliant on toxic substances, the shortcomings of this approach became increasingly apparent. The problem with polluting water is the very reason it was such an attractive sink for waste: it moves, meaning those who pollute don’t have to deal with the negative consequences, but downstream neighbors do.

An 1850 portrait representing clothing and devices a woman and her dog use to ward off cholera.

At first, localities used nuisance laws to force problematic polluters to change their behavior. By the early 1900s, some states had begun to lightly regulate certain pollutants, and many municipalities had begun to treat human waste. Most cities, however, still operated—and expanded—sewer systems that drained waste directly into waterways without treatment.

By the 1920s and 1930s, this ad hoc approach had become too cumbersome and ineffective to bring much relief. Even large water bodies such as the Ohio River obviously were polluted. Working through the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce in the 1930s, Cincinnati Street Railway employee Hudson Biery raised awareness about the water quality in the Ohio, starting a campaign for regional co-operation to control it.

In a memorable phrase, Biery noted that “citizens of Cincinnati don’t want to be reminded every time asparagus is served for supper in Pittsburgh or some other upstream community.” He and other Cincinnati businessmen formed the Stream Pollution Committee of the Chamber of Commerce, an influential group that included Robert A. Taft, the future U.S. senator and GOP leader known as “Mr. Republican.”

The Bellevue Incline in Cincinnati, Ohio, transports two trolleys and a horse and wagon in 1910.

The group pressed state governments in the eight states from which waters drained into the Ohio—from New York to Illinois—to develop solutions for the entire watershed.

Although the group took a conservative stance on regulation, the reluctance of upstream states to invest in infrastructure that would benefit mostly downstream communities quickly revealed that federal involvement would be necessary to coordinate and enforce action across state lines.

The eventual result, after much debate about the constitutionality of federal involvement in water pollution control (and the disruption of World War II), was federal legislation in 1948 creating the Ohio River Valley Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO).

Activists such as Biery had already convinced Congress to fund a comprehensive study of pollution along the Ohio, undertaken by the Public Health Service with the help of the Army Corps of Engineers. Scientists used the Kiska, a “floating laboratory,” and other research vessels to study water quality along the river and its tributaries.

Among the findings published in the multivolume Ohio River Pollution Survey in 1942, the Public Health Service determined that the sewage of 8.5 million people, two-thirds of it untreated, flowed into the Ohio, along with nearly 2 million tons of acid discharged from active and inactive coal mines. Biery called the survey “a bulwark of evidence” for “federal leadership.”

The very same year ORSANCO formed, Congress passed the first federal Water Pollution Act.

The 1948 act was a modest step for federal involvement, authorizing the Public Health Service to conduct further research and provide research grants to states to investigate the causes and consequences of water pollution and for the improvement of sewage treatment. The act also provided some loan financing for sewage treatment plant construction, although no funds were ever tapped.

President Dwight Eisenhower slowed federal involvement in water pollution control through the 1950s, although he reluctantly signed a 1956 revision to the Water Pollution Control Act that provided federal matching funds for localities to construct new or expanded sewage treatment plants.

In some ways, the 1956 act followed the model of the Depression-Era Public Works Administration, which had spent considerable sums of money on sewage systems, especially in smaller communities that otherwise would not have had the funds.

Despite the obvious progress in water quality and human health made through infrastructure investments, politicians continued to debate the proper role of the federal government in water pollution control. Eisenhower vetoed a more assertive and expensive Water Pollution Control Act in 1960, writing: “Because water pollution is a uniquely local blight, primary responsibility for solving the problem lies not with the Federal Government but rather must be assumed and exercised, as it has been, by State and local governments.”

Clearly Eisenhower was expressing conclusions derived from his political philosophy, which demanded a small federal government. Declaring water pollution a “local blight” might have made political sense, but it made no ecological sense.

The Colorado River irrigates Southern California’s agricultural Imperial Valley in 2007 (left). A 2018 map of the Colorado River drainage basin (right).

Edith Green, Democratic Representative from Oregon, asked incredulously: “Is the President aware of the fact that his own home state of Pennsylvania shares the Delaware River with New Jersey? That the States along the Mississippi and Missouri share a great waterway? That one of his favorite vacation spots—the State of Colorado, shares the river named after it with several other States?”

Before his death in 1967, Hudson Biery did see more progress at the federal level. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed a revision of the Water Pollution Control Act that allocated a substantial sum for sewage treatment plant construction.

Two additional revisions passed during Lyndon Johnson’s administration, in 1965 and 1966, both of which represented incremental expansions of federal investment in water pollution control and, just as important, a growing expectation that the federal government could and should act to solve what was decidedly not “a uniquely local blight.”

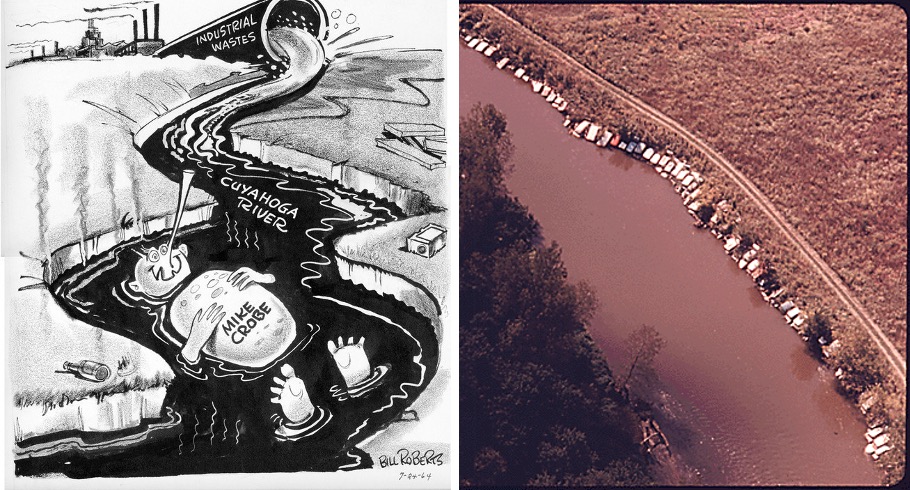

Burning River: The Cuyahoga

Investments in sewage treatment plants were essential, but they could only do so much to improve water quality, especially since industrial wastes tended to bypass sewage systems and flow directly into waterways. In addition, investments in pollution control couldn’t keep pace with suburban development and a growing American economy increasingly reliant on complex chemicals, including pesticides, PCBs, and lead.

Spending federal dollars on infrastructure was one thing, but the creation of federal pollution standards and enforcement mechanisms was another.

Among the Americans demanding greater federal involvement was Carl Stokes, mayor of Cleveland. Elected in 1967, Stokes understood that both water and air pollution were holding his city back. Residents were fleeing the polluted urban environment, depopulating the neighborhoods around the city’s massive steel mills.

Although Cleveland had built three large sewage treatment plants and was in the process of investing millions more in its system, Lake Erie was so frequently polluted that city beaches were rarely open for swimming, and the lake appeared to be dying. Stokes knew that only the federal government could provide the resources necessary to create real change.

In summer 1969, he saw an opportunity to make the case. On a Monday morning he stood on a charred railroad trestle with group of local reporters he had called together for a tour through the polluted Cuyahoga Valley.

The previous morning, June 22, a fire on the river had burned two low bridges and startled the long-polluted city. The Cuyahoga had caught fire more than a dozen times before, but not in many years, and Stokes wasn’t going to let the moment pass without pointing out the many ways Cleveland simply could not clean the river on its own.

A 1952 fire on the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio (left). Mayor Carl Stokes holds a press conference on a charred railroad bridge in 1969 after the Cuyahoga River burned (right). (Images courtesy of Special Collections, Cleveland State University Library.)

The state of Ohio regulated the steel mills and chemical factories along the Cuyahoga, for example, and they all had permits to pollute. The city had no authority to tighten control on industrial waste. And upstream, just a mile or so from where the river caught fire, suburban communities dumped their untreated sewage into the Cuyahoga. Cleveland couldn’t force them to link their pipes to the nearby Southerly Wastewater Treatment Plant.

All that waste, assuming it didn’t burn along the way, flowed slowly through the city and then inevitably into Lake Erie. Mayor Stokes asked a poignant question: How could the city of Cleveland prevent the Cuyahoga River from burning if it had no authority beyond its boundaries and only limited authority within them?

The imagery of the burning river—mostly borrowed from earlier fires rather than the unphotographed 1969 fire—along with less dramatic tales of pollution along other rivers that passed through large cities, such as the Hudson, the Delaware, and the Potomac, finally encouraged Congress to pass a comprehensive revision to the Water Pollution Control Act.

A 1964 editorial cartoon about Cuyahoga River industrial pollution (Image courtesy of Special Collections, Cleveland State University Library) (left). Aerial view of old cars secured along the banks of the Cuyahoga River near Cleveland to prevent erosion in 1975 (right).

That revision, passed in 1972 and known as the Clean Water Act, empowered the relatively new Environmental Protection Agency to set water quality standards and force states to create plans for improvement.

The federal government had finally moved beyond research spending and matching grants for infrastructure. The era of federal regulation had begun, and henceforth individual polluters needed to acquire federal permits and meet federal guidelines. Communities too were compelled to upgrade and maintain sewage treatment plants to ensure compliance.

The EPA gradually diminished pollution from point sources—individual, identifiable sources of liquid wastes. The ecological health of water bodies improved, recreational opportunities expanded, and threats to drinking water sources declined.

Brandywine Falls in Cuyahoga Valley National Park, Ohio, in 2014.

While the benefits of the Clean Water Act might be difficult to quantify, they have been undeniable. Fish have returned to some of the nation’s most polluted waterways, and the Cuyahoga River, one hopes, will never catch fire again.

Agriculture, Algae, and Lake Erie: The Maumee

Despite the progress, Carl Stokes was hardly the last Ohio mayor to express concern about water quality and to encourage further federal involvement.

In the summer of 2014, cyanobacteria made its way from Lake Erie into the city of Toledo’s water supply. The toxic blue-green alga had built up in the western end of Lake Erie, causing patches of it to resemble a bright pea soup. Toledo Mayor Michael Collins advised residents to stop drinking tap water, and Ohio Governor John Kasich declared a state of emergency, helping deliver potable water from distant sources.

Ohio’s National Guard distributes water during Toledo’s water crisis in August 2014.

The water crisis made the national news and raised questions. What caused the algal bloom? Was this a freak occurrence or a new reality? Were farms to blame, or perhaps the sprawling Detroit metropolis? How, in the early 21st century, could citizens of Toledo not have potable water because of environmental degradation?

More broadly, many people wondered why progress under the Clean Water Act had apparently stalled, and how even a large, critical waterbody such as Lake Erie could experience such degradation.

Five years later, the summer of 2019, the now-annual bloom covered 620 square miles of the lake. Everyone knew that phosphorus pollution fueled the extraordinary algal growth, but the problem was complex, with many causes including climate change.

This 2019 NASA image of Lake Erie near Maumee Bay, Ohio, shows a severe bloom of blue-green algal.

After decades of improvement, the great lake most at risk of dying in the 1960s was clearly in danger again. Fifty years earlier, phosphates from detergents had caused algal blooms in Lake Erie and other lakes.

At first, in the mid-1960s, the federal government had asked states and municipalities to improve sewage treatment plants to remove most of the phosphates contributed by detergents. This allowed soap companies, including Ohio’s own Procter & Gamble, to continue producing detergents consumers wanted. Very quickly this solution proved inadequate—and expensive.

As water quality in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario continued to decline, environmental activists pressured governments to act. In 1971, the state of New York banned the sale of phosphate detergents, joined by several other states and localities. The state of Ohio was slow to get involved, given the political influence of the soap industry, but by 1988 all Lake Erie counties in the state were under a similar ban.

With this slow adoption of regulation and improved sewage treatment, the detergent-related phosphate problem had been largely solved by the 1990s, and the Great Lakes—and many other bodies of water—had seen continuous improvement.

A hog farm in 2012. The floor slits permit waste drainage.

Since then, several things have changed in the Lake Erie basin, but the regulation has not kept up. The size of hog and poultry farms has grown enormously, generating massive amounts waste. The number of cattle in the Maumee watershed has also increased.

With manure piling up higher and the rains coming down harder—likely a consequence of climate change—more and more phosphorus has been pouring into the Maumee and then Lake Erie from as far away as northern Indiana. Add to that the phosphorus leaching from chemical fertilizers applied to the fields, and you have an intractable environmental crisis and a very practical question: How can the city of Toledo force farmers in Indiana to change their practices?

Answering this question is partly what the Obama administration attempted when it issued its Waters of the United States rule. A Supreme Court decision had opened the door to a more expansive legal definition of “waters” under the Clean Water Act, and the new rule would allow the EPA to better regulate nonpoint source pollution—particularly runoff from farms, which was often loaded with phosphates from artificial fertilizers.

A cow in front of a manure pile in 2012.

The expansion of regulation was designed to improve water quality in bodies of water where the problem had been especially intractable, including Chesapeake Bay and Lake Erie.

Fugitive Waters

Water pollution is never simply a local problem with purely local solutions. The stories of the Ohio, Cuyahoga and Maumee rivers—and hundreds more that might be told—all reinforce the same conclusion: Water moves across city limits, state lines, and international boundaries. Pollution that makes its way into water in one location is bound to make its way into human and natural communities downstream.

Local governments rarely have the ability to keep their waters clean, because they have neither the resources nor the jurisdiction and because the waters are always shared. This growing understanding of how water moves, and the ambiguities that had accumulated over the decades, led the Obama administration to define the “waters” of the United States more broadly.

After heavy rain, farm fertilizers and topsoil run off farm fields in 1999.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, the Republican Party positioned the use of agricultural chemicals as a property right and the 2015 rule as a dramatic government overreach, arguments that clearly resonated in rural America. The promise of regulatory relief helped Trump win the presidency, and his long list of rollbacks may help him keep it.

Meanwhile, Lake Erie is poised for another summer of toxic blooms, and other constituencies will work for a recommitment of the EPA to water pollution control. Environmental activists are reminded once again that no victories for environmental protection are permanent.

Read more from Origins on water and the global environment: The West without Water; Australia and the World Water Crisis; Fluoride; The River Jordan; Who Owns the Nile?; The Changing Arctic; Over-Fishing in American Waters; Whales Washed Ashore; and Dams.

Cleary, Edward J. The Orsanco Story: Water Quality Management in the Ohio Valley Under an Interstate Compact. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1967.

Congressional Record, vol. 106 (February 25, 1960), p. 3490.

Fleming, Kristen. “Generating a New Ohio River: Ecological Transformation in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” PhD. Dissertation. University of Cincinnati, 2019.

Kehoe, Terence. Cleaning Up the Great Lakes: From Cooperation to Confrontation. Dekalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1997.

McGucken, William. Lake Erie Rehabilitated: Controlling Cultural Eutrophication, 1960s-1990s. Akron: University of Akron Press, 2000.

Melosi, Martin. The Sanitary City: Environmental Services in Urban America from Colonial Times to the Present, Abridged. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008.

Milazzo, Paul Charles. Unlikely Environmentalists: Congress and Clean Water, 1945-1972. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006.

Pollution of Navigable Waters, Hearings before the Committee on Rivers and Harbors, House of Representatives, Seventy-Ninth Congress, November 1945.

Public Health Service, Ohio River Pollution Survey. Cincinnati, OH: Public Health Service, 1942.

Stradling, David and Richard Stradling. Where the River Burned: Carl Stokes and the Struggle to Save Cleveland. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015

Turner, James Morton and Andrew C. Isenberg. The Republican Reversal: Conservatives and the Environment from Nixon to Trump. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

United States Environmental Protection Agency, A Benefits Assessment of Water Pollution Control Programs Since 1972: Part 1, The Benefits of Point Source Control for Conventional Pollutants in Rivers and Streams (January, 2000).