On its “Milestones in UN History” website, the United Nations features smallpox eradication, explaining that “the world got rid of smallpox thanks to an incredible demonstration of global solidarity, and because it had a safe and effective vaccine.”

Eradication was a stunning achievement and that description of how it was accomplished feels especially poignant today when faith in both global solidarity and vaccines is ebbing. It’s a dangerous loss that threatens our ability to help people live longer, better lives, which makes now an opportune moment to remind ourselves how it was that humans were able to achieve so ambitious a goal.

Twice.

Here, I want to draw your attention to the second great disease eradication, the one you may well have never heard of: Rinderpest.

Indeed, the UN didn’t even include it on the milestones list. That is a mistake, because the second eradication is just as much a victory of science and internationalism as the first. It just never got the same attention because it did not infect humans; it infected their cattle.

They “Looked so Pitiful”

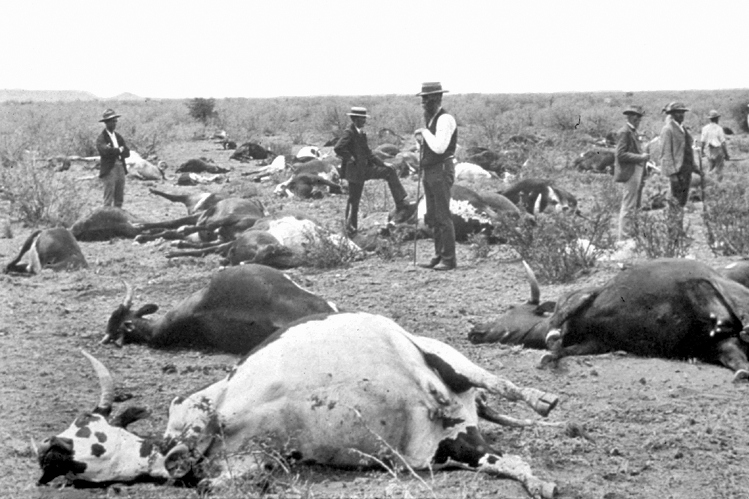

The disease was called rinderpest, the German word for “cattle plague,” and it was vicious. It spread quickly and thoroughly through herds of cattle and buffalo, often killing between 30% and 90% of those infected. They died miserable deaths.

Pope Clement XI’s personal physician, Giovanni Maria Lancisi, wrote around 1714 that they “looked so pitiful, held their heads low, their languishing eyes were filled with tears, and from their nostrils and mouth came mucus and saliva.” They “were often attacked by diarrhea with fetid matter of various colors and usually died during the first week, racked with coughing.”

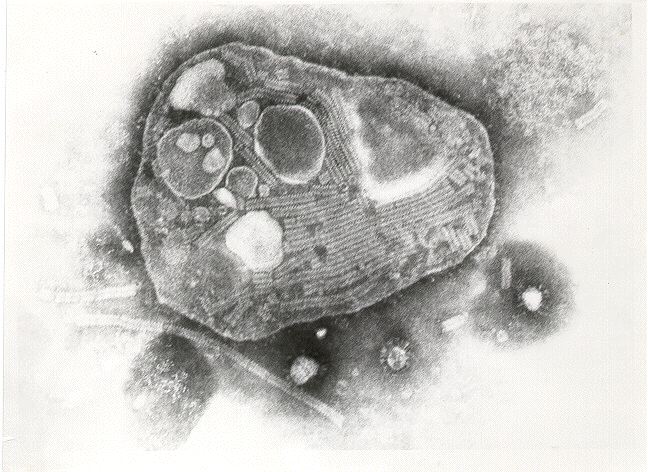

The closest relative of Rinderpest morbillivirus (RPV), the virus responsible for rinderpest, was Measles morbillivirus (MeV), the virus responsible for measles in humans. Scientists are still working out the details of the family tree, but most agree that measles emerged out of a spillover from cattle into humans.

While Rinderpest did not sicken and kill humans, it did kill their critical sources of food, labor, and security. In the eighteenth century, for example, the virus claimed an estimated 200 million cows in Europe, to the horror of their owners. This was why Pope Clement XI had sent Lancisi to investigate.

The physician recommended culling and quarantines. Governments across Europe explored additional means of disease control whenever rinderpest reached their borders. In the 1750s, during the worst of the three waves that hit Europe that century, multiple individuals published their experiments with inoculation.

Governments built the first veterinary colleges and urged further research. In 1863 they organized the first international conference of veterinary surgeons in Hamburg to better coordinate their efforts. While working hard to keep rinderpest out of their own fields, however, they helped spread it to other places, with devastating consequences.

A Disease of Imperialism

In the late 19th century, rinderpest became a disease of imperialism, aided in its movement across Africa and Asia by new technologies and networks of exploitation. Cattle shipped to the Philippines in 1886 to feed Spanish colonial authorities brought rinderpest with them. Rivers became clogged with dead buffalo in an outbreak with a probable 90% mortality rate.

A similarly destructive outbreak unfolded across much of Africa after Italian forces brought infected cattle to Massawa (now in Eritrea) in 1887. The disease quickly spread eastward and southward. A horrific famine followed in its wake.

“The enormous extent of the devastation it caused in Africa can hardly be exaggerated,” British colonial administrator Lord Frederick Lugard reported. But he found his silver lining, writing that in “some respects” it “has favored our enterprise. Powerful and warlike as the pastoral tribes are, their pride has been humbled and our progress facilitated by this awful visitation. The advent of the white man had else not been so peaceful.”

At least for them.

Imperialists used rinderpest to their advantage, but they also feared it, and the quarantine strategies that had worked so well in Europe proved less effective in places with so many wild animal carriers. But there was now another possible option.

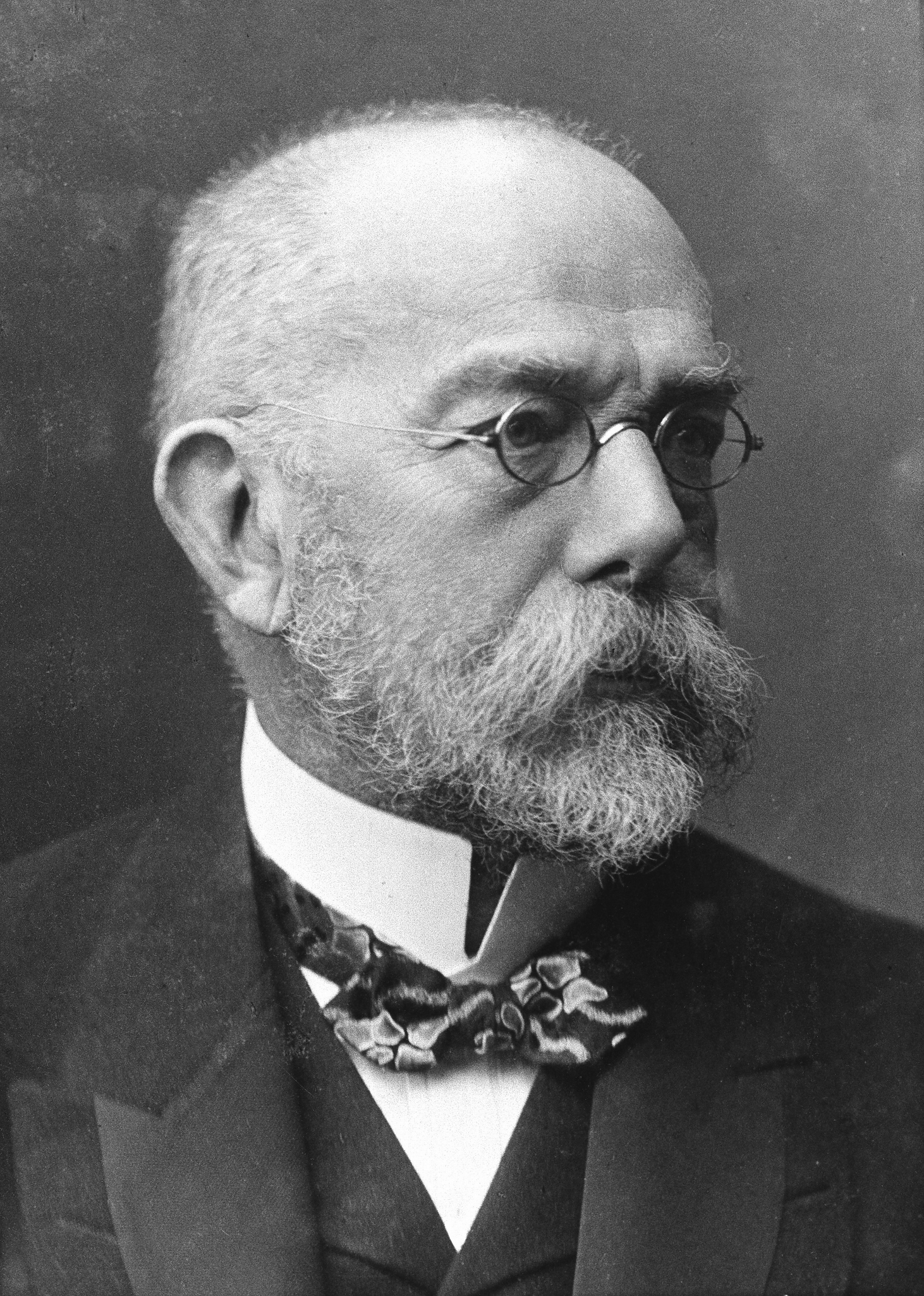

In 1896, Cape Colony officials asked Robert Koch to come from Berlin to create a vaccine. No one knew the microbe responsible for rinderpest, but Koch was undeterred.

After all, he wrote, “we know the microbe of neither small-pox nor of rabies, and yet we have succeeded in devising prophylactic inoculations against both diseases dependent upon the fact that infective material can be weakened and converted into a so-called vaccine in the one case by passage through the animal body, in the other by drying.”

Koch’s efforts to create a rinderpest vaccine involved passaging the virus in goats, pigs, antelopes, donkeys, mules, dogs, eagles, pigeons, chickens, rabbits, mice, guinea pigs, and a secretary bird. He tried drying infected blood, reliquefying it with water, and then injecting it into un-infected animals. He tried using chemicals to kill the microbe and using serum or bile from animals who had survived infection.

None of these experiments brought clear success, and his efforts were cut short by an order from the German government to join an expedition to India to study bubonic plague (he continued working on rinderpest there). Local scientists ended up settling on inoculation via a mixture of infected cattle blood and serum. It was a far from perfect solution, however, and the search for something more effective continued.

Scientific Breakthroughs and International Cooperation

In the early 20th century, scientists around the world continued along the same lines of exploration that Koch had pioneered. They used chemicals to make inactive vaccines that could not replicate in a host but could still trigger enough of an immune response to provide temporary safety. These were helpful, but they didn’t provide long-lasting immunity.

Scientists also tried attenuation (or weakening) by the passage of the virus through multiple foreign animal bodies to force the virus to mutate into a new strain that might eventually be injected into cattle without making them sick. This is what Koch had been trying with his goats and guinea pigs.

Almost every attempt to create an active rinderpest vaccine ended in failure, but through years of diligent work, researchers were able to create a few. Two particular facts about RPV made it possible.

First, RPV mutates quickly, so researchers could inject an animal (rabbits and goats proved to be the best candidates at this point) and then did not have to wait very long before they could take infected tissue from that animal, inject it into another, and so on. This is the passaging part of the vaccine process.

Second, RPV exists as a single serotype. Immunity to any strain of the virus protects against all strains of the virus.

Following an outbreak in Antwerp in 1920 in a shipment of cattle from India, governments moved into action. In 1924, the Office International des Epizooties (OIE) in Paris was created with the hope of creating broader rinderpest control through vaccines, which would not hinder commerce as quarantine and culling did.

The OIE hosted meetings and published information about outbreaks, sanitary measures, and disease research. It was not officially part of the League of Nations, but it was part of the internationalism that inspired League health and economic missions. Proponents were animated by a faith that international cooperation and scientific advancement could build a better world for all.

Rinderpest and World War II

The outbreak of war in the 1930s hardened their resolve and grew their ranks. It wasn’t enough just to defeat the Axis Powers, they explained; the Allies needed to also defeat hunger and economic insecurity. The rinderpest vaccines would help them do it, first, by protecting the critical Allied food supply chain that originated in the fields and farms of North America.

Canadian and U.S. officials feared an Axis biological attack with rinderpest. A 1940 British report on the possibility had noted, “No disease is so feared in Europe,” so the Germans “might hesitate to set up the necessary virus factory owing to the danger of escape of infection.” But would they hesitate to unleash it in North America?

Rinderpest had never broken out in North America. If it did so now, a scientist reported at a 1941 meeting of U.S. and Canadian officials on biological warfare, it would spread “rapidly, extensively, and disastrously.” Participants agreed to immediately secure a safe space for a laboratory to work on large-scale vaccine production.

Officials turned to Grosse Île, a small island in the Saint Lawrence River that had served as a quarantine station for over 100 years before being shut down in 1937.

There they built a top-secret laboratory to create an effective vaccine at the lowest possible expense that could be produced in sufficiently massive quantities and survive storage. They hoped that they would never have to use it, but they needed it just in case.

The joint U.S.-Canadian effort was run by Dr. Richard Shope, a renowned virologist from the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research.

He and his team used the new finding that the influenza virus could grow in eggs to do the same with a strain of rinderpest that had been kept “alive” by researchers in cattle in Kenya through needle-passaging since 1911. The virus journeyed to Canada in glass ampules filled with dried pieces of bovine lung tissue.

To the delight of Shope and his team, the virus proved still infectious upon arrival. To their additional delight, they discovered it could be attenuated into an effective vaccine via repeated passages in eggs alone, which saved them from having to use animals. But the fact that the virus had survived the journey from Kenya emphasized the threat facing them. It could only take a little bit of dried tissue to trigger a disaster.

Japanese and German scientists had the same thought.

In 1942, Dr. Junji Nakamura, a scientist at Japan’s Busan Institute in Korea, published a report of his successful creation of new rinderpest vaccine via passaging a particular strain of the virus through rabbits.

The government was thrilled with his success, which they immediately put to work protecting their cattle from the ever-present threat of rinderpest in East Asia. They also immediately put Nakamura to work on the new task of assisting efforts to employ rinderpest as a weapon of war.

Army veterinarian Noboru Kuba headed the work, creating a powder mixture of dried ground infective lymph node tissue with refined flour that could, he found to his delight, successfully spread rinderpest in cattle made to inhale it.

He had his weapon: an explosion of infective powder. For its delivery system, he proposed attaching boxes of rinderpest powder to the paper and paste balloon bombs that the Japanese were building to be carried across the Pacific in the jet stream.

To Kuba’s frustration, the army ultimately rejected his proposal (at the urging, Kuba later wrote, of Hideki Tojo). They launched thousands of balloon bombs in 1944 and 1945, but none carried rinderpest.

The Japanese were not the only ones considering such possibilities. Though Hitler banned offensive work on biological weapons early in the war, he had allowed research on defensive measures. A 1943 German report warned that though the Allies had rejected the “dissemination of human diseases,” “the entire German veterinary profession should become well conversant with rinderpest.”

Captured German scientists later reported that Heinrich Himmler had quietly attempted to initiate research on turning rinderpest into an offensive weapon. Since there was no RPV in any German lab, he attempted to have some brought in from Turkey in glass ampules of dried tissue. In this case, however, the virus did not survive the journey. Disappointed, Himmler said they would try again, but further efforts did not come to anything.

Enthusiasm for International Action

Thankfully, rinderpest did not become yet another weapon in that war where horror followed upon horror, but the research that had been done to defend against it did not go to waste.

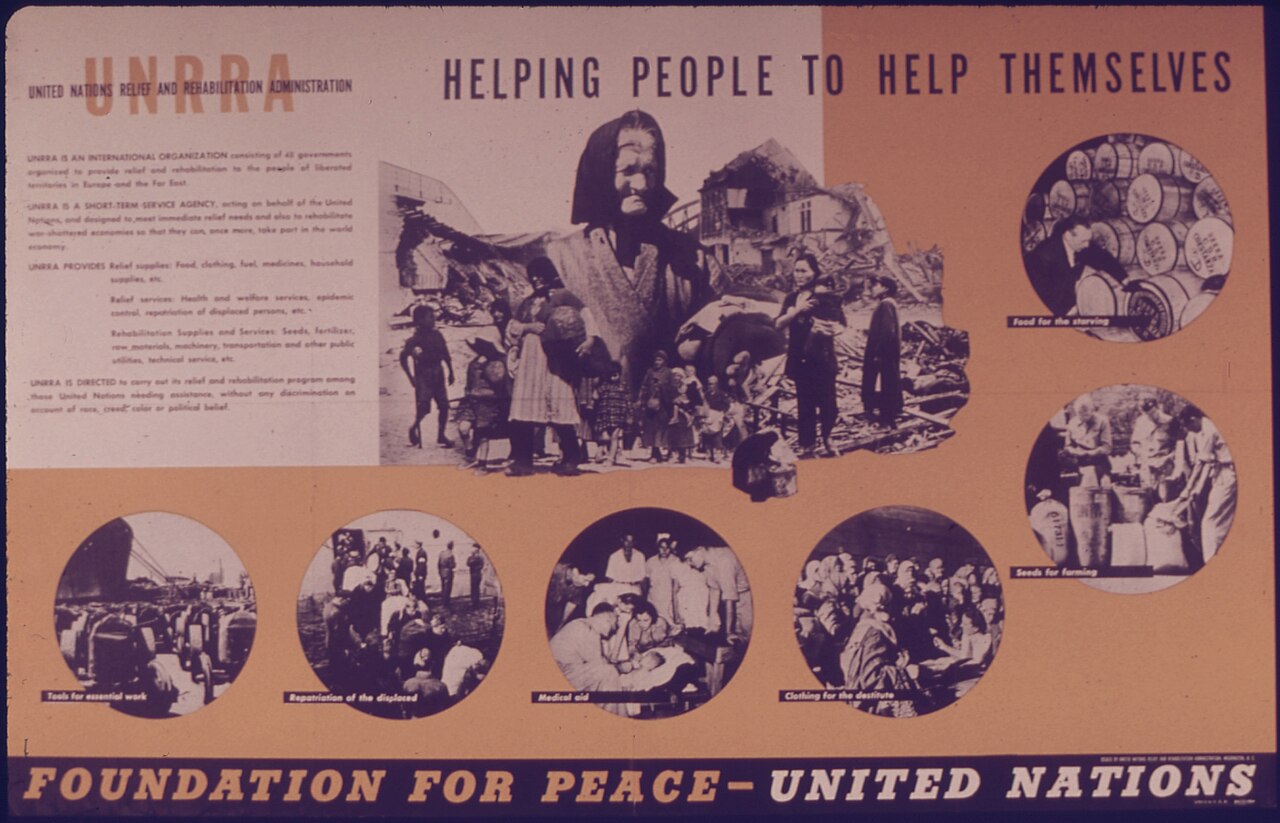

Along with the vaccine research that scientists had been doing in colonial laboratories around the world, it became part of the United Nations effort to secure “freedom from want,” initially through the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA).

Relief workers followed in the wake of Allied armies with food, medicine, and blankets, but very quickly also seeds, fertilizers, tractors, and more, including the Grosse Île rinderpest vaccines that the U.S. and Canadian governments had stockpiled in case of attack.

UNRRA officials shipped hundreds of thousands of doses of Grosse Île vaccine to China to combat an ongoing outbreak. These vaccines required refrigeration, which complicated getting them into the countryside, but local technicians packed them in metal thermoses filled with ice and tried their best.

The goal was to vaccinate 90% of the cattle and buffalo in a region; they branded an “R” on the hip after injection to keep track.

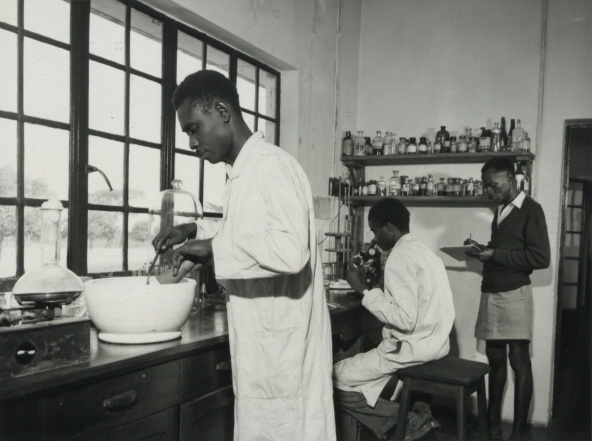

Chinese scientists also got help from UNRRA to build up their local vaccine manufacturing capabilities. When efforts to grow seed virus sent from Grosse Île in eggs did not work, they turned to Junji Nakamura’s rabbit-passaged vaccine, which they had acquired when the Beijing branch of the National Research Bureau of Animal Industry went back into Chinese hands.

Infected rabbits were carried alive into the field and then killed to make vaccines wherever needed, freeing technicians from dependence upon refrigeration. Rabbits were scarce in many parts of China, however, so efforts to produce an avian vaccine continued.

By the end of 1947, Chinese scientists were producing multiple kinds of rinderpest vaccines in over 30 laboratories. Other countries were eager to do the same. They too went to the United Nations for help, citing its promise “to employ international machinery for the promotion of the economic and social advancement of all peoples.”

The new UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) was a vital part of that machinery, one of the multiple agencies designed, the director of UNESCO explained in 1947, “to promote the international application of science to human welfare,” in part by “banishing germ-causing disease.”

This effort, he argued, would make a better, safer world, for “as the benefits of such world-scale collaboration become plain (which will speedily be the case in relation to the food and health of mankind) it will become increasingly more difficult for any nation to destroy them by resorting to isolationism or to war.”

This was a bold vision that depended on the commitment of the world’s wealthiest nations to support assistance to its poorest. Enthusiasm was widespread as the war ended, but it was not guaranteed to last. Time was of the essence in making sure those benefits did indeed “speedily” become plain.

Determined to succeed, officials at the new UN agencies focused on problems that they believed could be rapidly solved with the tools at hand. The discovery of DDT during the war encouraged the leadership at the World Health Organization (WHO) to focus on malaria control.

The multiple new rinderpest vaccines had the same influence on officials at FAO, with some arguing as early as 1946 that the technology had made eradication “a practical possibility.”

FAO partnered with the OIE, foreign aid agencies, colonial bureaucracies, and other organizations to help countries across Africa and Asia mount national rinderpest vaccination campaigns. FAO transported strains of the virus between labs in different countries, hosted meetings that brought nations together to discuss vaccines, and helped nations secure access to new technologies of vaccine production.

The efforts bore fruit.

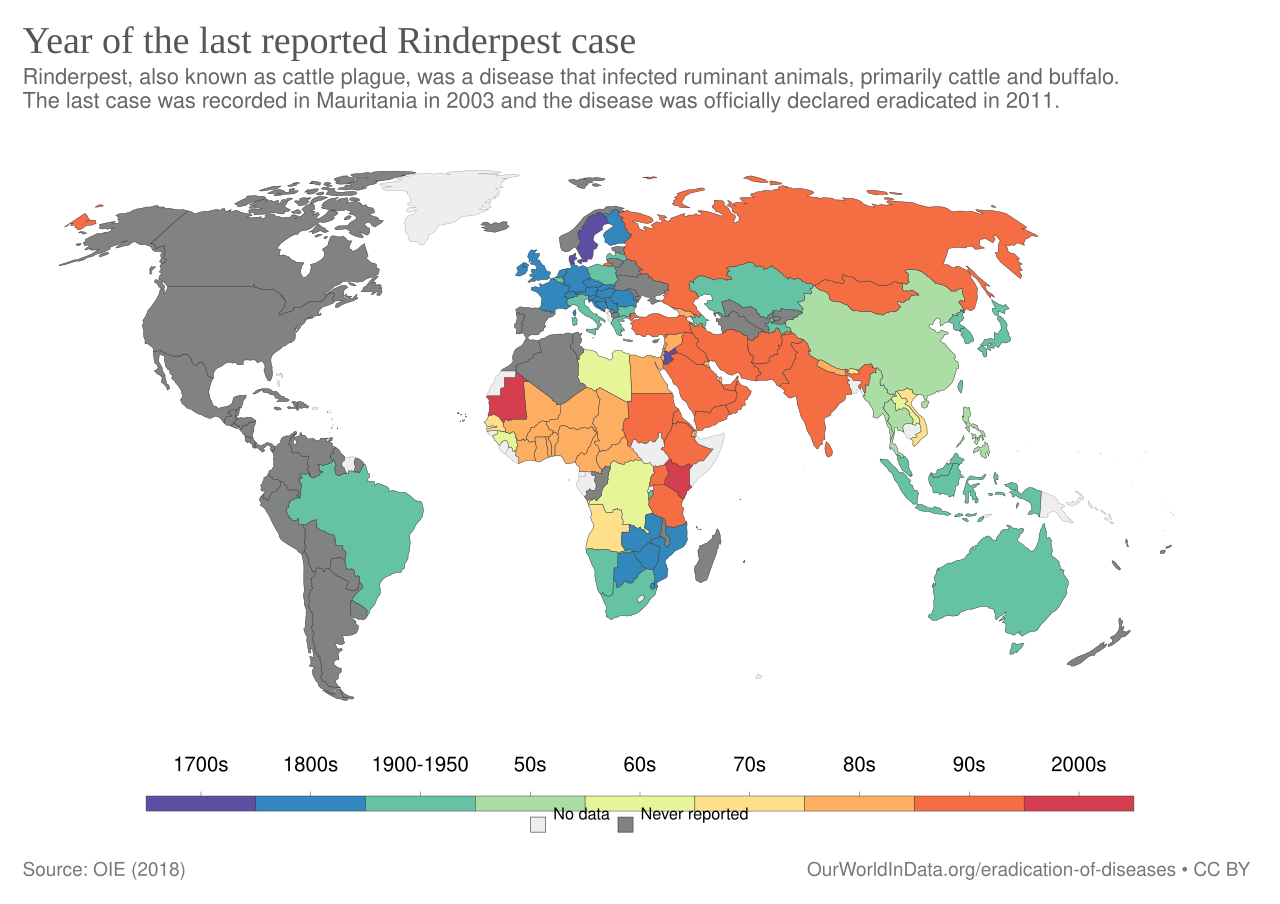

In 1957, FAO’s director general wrote that just ten years earlier “it was estimated that some two million cattle were dying in the Far East every year from rinderpest alone. Today’s figure is probably less than 50,000.”

Several nations had eliminated it within their borders, and many others had it under control. There was also, he continued, “confident hope that it will subsequently be driven out of the whole of Africa.”

National- and regional-level rinderpest campaigns continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s, benefitting enormously from a new vaccine developed by Dr. Walter Plowright that was safe for all kinds of cattle of any age, conferred lifetime immunity, and was cheap and easy to produce. Its only weakness was that it required refrigeration.

Efforts proved so successful that the goal of rinderpest eradication gave way to satisfaction with rinderpest control.

Unfortunately, however, it did not stay controlled. Outbreaks erupted in multiple locations. The most devastating of them in the early 1980s killed an estimated 100 million cattle in Africa. Affected communities wrestled with food insecurity, economic devastation, and social strife.

Eradication at Last

The devastation inspired a renewed focus on the virus. FAO and the OIE worked with development partners to help countries launch the Pan-African Rinderpest Campaign in 1986 and the West Asian Rinderpest Eradication Campaign in 1989.

Nations outside the regional groupings—most notably India—used the growing international attention to secure outside support for revitalized national campaigns.

New technology helped, particularly a new thermostable vaccine that could survive 30 days without refrigeration. In addition, heeding the lessons of the fight against smallpox, the OIE created a three-stage Pathway structure to move countries from vaccination to surveillance.

Considering all these developments, FAO and OIE officials decided that the time was right for a final coordinated push to drive rinderpest permanently out of circulation and launched the Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme (GREP) in 1994.

As its name makes clear, GREP was not itself a campaign, but a program that provided global coordination to multiple separate campaigns, uniting them through shared research, technology, information, and purpose. GREP was the “international coordination mechanism” that guided the world toward eradication one country at a time.

A key focus was encouraging nations to shift power to local communities for vaccination and monitoring, a change made possible by the thermostable vaccine. Global cooperation empowered grassroots action. Nations moved individually through the OIE’s Pathway: shifting from vaccination into surveillance.

Rinderpest was last detected in wild buffaloes in Mount Meru National Park in Kenya in 2001. The last vaccination occurred in 2006. Surveillance teams kept searching for the virus in both wild and domesticated animals but couldn’t find it.

In 2011, the OIE (now the World Organization for Animal Health, though it continued to use the OIE acronym until 2022) and FAO declared that the world had “achieved freedom from rinderpest in its natural setting.”

Thanks to decades of hard work by scientists, veterinarians, agency officials, aid workers, community leaders, livestock owners, and more, the virus exists now only in laboratories.

And there it remains, its confinement another reminder of what vaccines and “global solidarity” can achieve. We forget that at our peril.

Amanda Kay McVety, The Rinderpest Campaigns: A Virus, Its Vaccines, and Global Development in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Clive A. Spinage, Cattle Plague: A History. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2003.

Thomas Barrett, Paul-Pierre Pastoret, and William P. Taylor, eds. Rinderpest and Peste des Petits Ruminants. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006.

Karen Brown and Daniel Gilfoyle, Ed. Healing the Herds: Disease, Livestock Economies, and the Globalization of Veterinary Medicine. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010.

Jean Blancou. History of the Surveillance and Control of Transmissible Animal Diseases. Paris: OIE, 2003.

Peter Roeder, Jeffrey Mariner, and Richard Kock, “Rinderpest: the veterinary perspective on eradication.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 368:20120139 (August 5, 2013).