In 2020 Americans are marking the 100th anniversary of women's suffrage. The centennial seems particularly relevant as record numbers of American women are running for, and winning, elective office. This month, however, historian Katherine Marino reminds us that the movement that produced the 19th amendment had both deep historical roots and happened in a global context.

The history of the US woman suffrage movement is usually told as a national one. It begins with the 1848 Seneca Falls convention; follows with numerous state campaigns, court battles, and petitions to Congress; and culminates in the marches and protests that led to the Nineteenth Amendment.

That story, however, overlooks how profoundly international the struggle was from the start. Suffragists from the United States and other parts of the world collaborated across national borders. They wrote to one another; shared strategies and encouragement; and spearheaded international organizations, conferences, and publications that in turn disseminated information and ideas.

Many were internationalist because they understood the right to vote as a global goal.

Enlightenment concepts, socialism, and the abolitionist movement helped U.S. suffragists universalize women’s rights long before Seneca Falls. They drew their inspiration not only from the American Revolution, but from the French and Haitian Revolutions and, later, from the Mexican and Russian Revolutions.

Many were immigrants who brought ideas from their homelands. Others capitalized on the Spanish-American War and World War I to underscore contradictions between the United States’ growing global power and its denial of woman suffrage.

Many women of color used the international stage to challenge U.S. claims to democracy, not only in terms of women’s rights but also in terms of racism in the United States and in the suffrage movement itself.

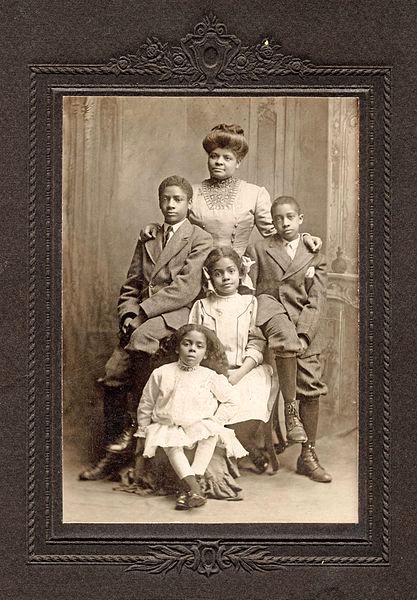

Ida B. Wells-Barnett with her four children in 1909.

The complex international connections and strategies that suffragists cultivated reveal tensions in feminist organizing that reverberated in later movements and remain instructive today.

These multiple, and sometimes conflicting, international strands worked in synergy, bolstering the suffrage cause and expanding the women’s rights agenda. The resources that women shared with one another across national borders allowed suffrage movements to overcome political marginalization and hostility in their own countries.

A radical challenge to power, the U.S. movement for women’s voting rights required transnational support to thrive.

Abolitionism and the Transnational Origins of Women’s Rights

Although the American Revolution and U.S. circulation of Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) activated discussion of women’s rights, the transatlantic crucible of abolitionism truly galvanized the U.S. women’s rights movement.

The antislavery movement, which Frederick Douglass called a “peculiarly woman’s cause,” provided broad ideals of “liberty” as well as key political strategies that suffragists would use for the next 50 years—the mass petition, public speaking, and the boycott.

Transatlantic networks of organizations, conferences, and publications drove abolitionism. Women in the United States looked to their British sisters, who in 1826 made the first formal demand for an immediate rather than gradual end to slavery.

Boston reformer and African American abolitionist Maria Stewart—one of the first U.S. women to call publicly for women’s rights before a mixed-race and mixed-sex audience—embraced a diasporic vision of freedom when she asked in 1832: “How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles?”

Her vision of rights for African American women, specifically, in the face of economic marginalization, segregation, and slavery, drew upon universal rights that she found expressed not only in the U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence but in the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. It was also inspired by the Haitian Revolution, the largest slave uprising ever, from 1791 to 1804.

The hostility Stewart and other female abolitionists faced for overstepping boundaries of female propriety by speaking out in public threw into sharp relief that, as abolitionist Angelina Grimké put it, “the manumission of the slave and the elevation of woman” should be indivisible goals.

At the 1837 First Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, an interracial group of 200 women called for women’s rights. When Quaker minister and abolitionist Lucretia Mott and other female delegates were excluded from the 1840 World Antislavery Congress in London, Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton hatched the idea for a separate women’s rights convention.

The resulting 1848 Seneca Falls Convention and its demands for women’s rights were only possible because of abolitionists’ groundwork and the broad meanings of emancipation flourishing in the United States and in Europe, where revolutions had broken out that year. Calls for universal suffrage from British Chartists, the first mass working-class movement in England, directly inspired Stanton’s idea to include the right to vote in the convention’s Declaration of Sentiments.

Mott explicitly connected the Declaration to the 1848 abolition of slavery in the French West Indies, opposition to the U.S. war with Mexico, and Native American rights. She and Stanton also found models in the matrilineal communities of the Seneca people, wherein women held political power.

The right to vote proved to be the convention’s most controversial demand, and abolitionist Frederick Douglass was one of its most avid proponents.

Suffrage became key to the many U.S. women’s rights conventions Seneca Falls set into motion, inspiring and drawing on the support of women in Europe and elsewhere, including immigrant women in the United States. In 1851, from Paris jail cells, revolutionary women’s rights activists cheered U.S. women’s activism.

In March 1852, German immigrant and socialist Mathilde Anneke started the first women’s rights journal in the United States published by a woman, the Deutsche Frauen-Zeitung. After the Prussian victory over the Palatinate and the crushing of the 1848 revolutions, she fled the German lands to the United States, where she became a friend of Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

Polish-born immigrant and abolitionist Ernestine Rose expressed her global vision for suffrage in 1851: “We are not contending here for the rights of women of New England, or of old England, but of the world.”

Such ideas resonated with Sarah Parker Remond, whose life reflects the overlapping transnational abolitionist and woman suffrage movements. In 1832 she helped found the first female antislavery group in Salem, Massachusetts. In 1859, while on an antislavery speaking tour in England, Remond reported that she was “received here as a sister by white women for the first time in my life. … I have received a sympathy I never was offered before.”

Mathilde Franziska Anneke, 1817-1884 (left); Ernestine Rose, 1810-1892 (top right); Sarah Parker Remond, 1826-1894 (bottom right).

For Remond, transnational connections became a concrete way to escape racism in the United States. She settled permanently in Italy, where she became a physician. In 1866, Remond affixed her name to John Stuart Mill’s petition to the British Parliament for woman suffrage.

Internationalism was also key to African American abolitionist and suffragist Mary Ann Shadd Cary, who moved to Canada after the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act for fear it would endanger free blacks like herself and enslaved people. She knit connections among her work for black civil rights in Ontario, abolitionism, and the U.S. woman suffrage movement, founding one of the first suffrage organizations for black women in the United States.

Transnational Organizing and “Global Sisterhood”

Transnational connections initiated by the 19th-century abolitionist movement only grew in the following decades. After construction of the first transatlantic telegraph lines in the 1860s, communications, travel, and transnational print culture helped produce the first international organizations for women’s rights that drew significantly on U.S. women.

These included the World’s Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), founded in 1884 by U.S. temperance leader Frances Willard; the International Council of Women (ICW), founded in 1888 by Stanton and Anthony; the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA, later renamed the International Alliance of Women), founded in 1904 and presided over by Carrie Chapman Catt (then president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association); and Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), founded in part by U.S. social settlement worker Jane Addams in 1915.

Alongside each organization’s particular focus—international arbitration, universal disarmament, temperance, married women’s civil rights, anti-trafficking of women, equal pay for equal work, among others—a global goal of women’s political equality drove them.

These organizations connected women across the lines of nation, culture, and language and had overlapping memberships. They hosted international conferences, and they helped spearhead publications such as the IAW’s Jus Sufffragii and the ICW’s Bulletin, which shared information about suffrage organizing in Asia, Latin America, Europe, and other parts of the world.

Of the four, the WCTU inspired the most dramatic grassroots suffrage activism, becoming the largest women’s organization in the world, with more than 40 national affiliates.

A parade float created in 1920 by WCTU members in Bristol, Tennessee.

An outgrowth of the U.S. Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (1874), the WCTU argued that women could use their votes to promote temperance and end men’s alcohol-infused violence. The organization transformed the goal of woman suffrage into a legible and compelling one for large numbers of women.

Spearheading the first organized suffrage efforts in the white British colonies of South Africa, New Zealand, and South Australia, the WCTU was responsible for the world’s first national suffrage victories—in New Zealand in 1893 (PDF File) and in Australia in 1902.

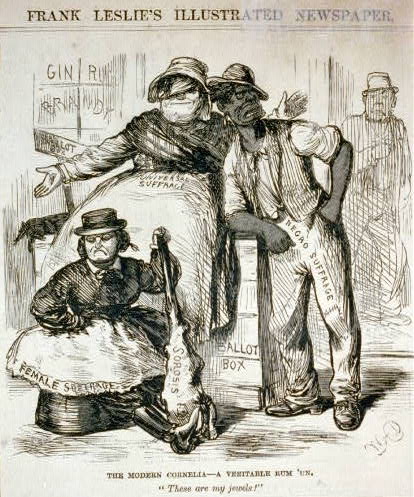

Although these groups spoke of “global sisterhood,” their memberships were predominantly Anglo-American and European, and their publications usually only published in French, English, and German, in spite of demands to expand beyond these languages from women in Spanish-speaking countries and other parts of the world. These international groups generally marginalized, excluded, or, in the U.S. WCTU’s case, segregated women of color.

These groups often reflected what historians have called “imperial feminism”—a belief that white, Western women would “uplift” women in “uncivilized” parts of the world. This logic went hand in hand with some suffrage efforts.

WCTU missionaries in Hawaii who sought to secure woman suffrage there in the 1890s allied with white U.S. business and military interests establishing imperial control over the island. Suffragists also demanded the vote in the United States’ imperial acquisitions from the 1898 Spanish-American War—the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba—both as part of a civilizing mission and to force discussion of a federal suffrage amendment in the United States.

Meanwhile, as they celebrated early suffrage victories within the western United States in the same period, most white suffragists ignored that these states denied the right to vote accorded native-born women to many Asian American, Mexican American, and Native American women.

African American suffragists powerfully critiqued Anglo-American dominance on the international stage and within the U.S. suffrage movement as they made important contributions to it. They also continued to connect global ideals of “freedom” with local women’s rights issues, expanding the international agenda to address such goals as universal suffrage for men and women, anti-lynching, and education.

Former abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, a pivotal African American civil rights and women’s rights leader, spoke at the 1888 founding of the ICW in Washington, D.C. and oversaw the formation of many “colored WCTU” groups that contributed to school suffrage victories in several states in the 1890s.

Madame C.J. Walker (1867-1919) was a member of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs.

On a speaking tour in England, the anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells brought global attention to WCTU president Willard’s failure to defend African American men lynched on false rape accusations. Wells also founded the most vital African American woman suffrage group in the country, the Alpha Suffrage Club, in Chicago, and at the 1913 suffrage March on Washington, she refused to be relegated to the back of the procession—reserved for African American women—and instead marched with the Illinois delegation.

In 1904, Mary Church Terrell, the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, spoke in fluent German at the ICW meeting in Berlin, pointing out that a global women’s rights agenda must include attention to black women’s unequal access to many rights, including education and employment. Newspapers in Germany, France, Norway, and Austria lauded her speech.

International Influences on the Modern Suffrage Movement

At the end of the 19th century, a more modern and militant suffrage internationalism emerged. A growing embrace of the term “feminism”—implying a movement that demanded women’s full autonomy—along with working women’s strong public presence, international socialism, and the Russian Revolution, contributed to the idea of a new womanhood breaking free from old constraints.

International socialism had long upheld universal, direct, and equal suffrage as a demand, but in the 1890s, German socialist firebrand Clara Zetkin revived that goal, spearheading the inclusion of woman suffrage in the 1889 Second International in Paris.

This gathering of socialist and labor parties from 20 countries in turn fostered vigorous women’s movements in Germany, France, and elsewhere in Europe. In Finland (then part of the tsarist Russian empire), socialist feminists and the Social Democratic Party were critical to the country’s woman suffrage victory in 1906. In 1917, after the February Revolution, Russia granted women the right to vote and the right to hold public office.

Socialism, and the growing numbers of working women it inspired, breathed new life into the U.S. suffrage movement. In 1909, women workers in New York demanded the right to vote, launching what became International Women’s Day. Over the next six years, working women exploded in labor militancy, viewing the vote as a tool against unjust working conditions and for what Polish-born labor organizer and suffragist Rose Schneiderman called “bread and roses.”

The 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that claimed the lives of 145 workers, most of them young, immigrant women, made suffrage more urgent. Collaborations with middle-class reformers helped spread many of the tactics that suffragists later employed on a wider scale: mass meetings, marches, and open-air street speaking.

Immigrants and women from throughout the Americas were key to these efforts, and to connecting suffrage to broad social justice goals. In cigar factories in Tampa, Florida, the Puerto Rican anti-imperialist, anarchist, and feminist Luisa Capetillo inspired African American, Cuban American, and Italian American women workers with calls for woman suffrage, and for free love, workers’ rights, and vegetarianism.

From Texas, Mexican-born feminist Teresa Villarreal, who had fled the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, supported the Mexican Revolution, the Socialist Party, and woman suffrage. With her sister Andrea, Villarreal published that state’s first feminist newspaper, La Mujer Moderna (The Modern Woman), and El Obrero: Periódico Independiente (The Worker: Independent Newspaper) in 1910.

In 1911, after the First Mexican Congress in Laredo, Texas, journalist Jovita Idar praised woman suffrage in La Crónica (The Chronicle), where she connected the vote to her longstanding demands for Mexican American civil rights.

Socialist, working-class suffrage militancy in England also galvanized the British Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst. This group, which broke away from the larger, more moderate National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett, became the driving force in the British suffrage movement for nearly two decades and influenced militant activism around the world, including in China.

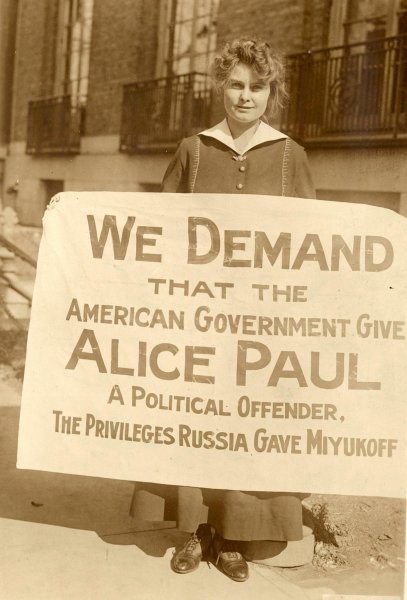

After the U.S. suffragist Alice Paul, one of Pankhurst’s followers, was arrested in London in 1912, she helped organize the 1913 suffrage march in Washington, DC and founded the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, later renamed the National Woman’s Party (NWP), which focused on a federal constitutional suffrage amendment.

Lucy Branham in 1917 picketing to support Alice Paul, founder of the National Women’s Party.

Its confrontational suffrage strategies of civil disobedience and picketing government buildings were inspired in large part by the WSPU. The NWP sash of purple, white, and yellow was modeled on the WSPU purple, white, and green one. Though U.S. suffragists generally called themselves “suffragists,” a few even took on the British term “suffragette” (initially coined by the British Daily Mail as an epithet) to signal their radicalism.

World War I unleashed a wave of suffrage legislation in Europe and accelerated the U.S. suffrage movement. In the five years after 1914, woman suffrage was adopted in Denmark, Iceland, Russia, Canada, Austria, Germany, Poland, and England.

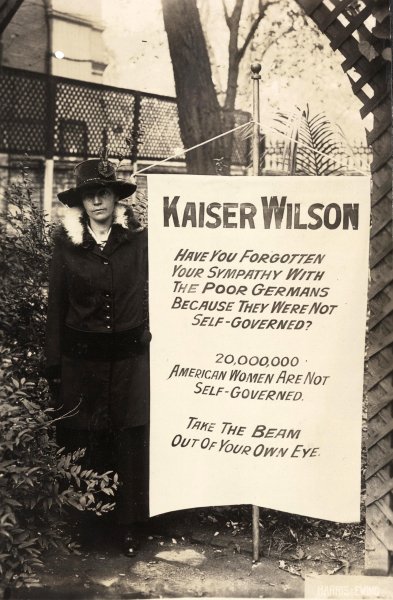

Although the NWP had already been picketing the White House for several months, it was only when they embarrassed President Woodrow Wilson in front of a visiting Russian delegation, whose wartime cooperation he was trying to secure, that the first six suffragists were arrested on charges of obstructing traffic.

Many U.S. women were thereafter imprisoned for suffrage activism. The violence they faced on the picket line (for holding signs saying “Kaiser Wilson” amid rabid anti-German sentiment, for example) and in jail, with forced feedings during hunger strikes, became international news.

Virginia Arnold poses with the “Kaiser Wilson” banner in 1917.

By January 1918, international momentum compelled Wilson to announce his support for suffrage as he promoted the Unites States as a beacon of democracy.

By this time, the House had already passed the suffrage amendment against Senate opposition, but Wilson’s endorsement was significant to US and international public opinion. In Uruguay, suffragists utilized Wilson’s support to push their legislators toward suffrage.

Two more years of federal and state lobbying and organizing led to ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920.

For Crystal Eastman, a pacifist, enthusiast of the Russian Revolution, and cofounder of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), this accomplishment represented not an end, but a new beginning—one with international significance: “Now [feminists] can say what they are really after; and what they are after, in common with all the rest of the struggling world, is freedom.”

The International Afterlives of the U.S. Suffrage Movement

Struggles for women’s voting rights did not end with ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Though African American women in other parts of the United States became voters, those living in the South faced the same obstacles southern states had adopted to counter the Fifteenth Amendment—residency requirements, poll taxes, and literacy tests backed up by threats and violence.

It took another major struggle for full enfranchisement, one that was a vital part of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, before Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that actualized the promises of the Fifteen and Nineteenth Amendments.

For many African American women, the denial of their rights in the United States drove new transnational activism. In the 1920s and 1930s, they collaborated with women from Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere in the International Council of Women of the Darker Races (1922).

Pan-Africanist and leftist organizing connected demands for women’s political autonomy with those for antiracism, anticolonialism, and black nationalism. Black women’s self-determination became critical to broad and transformative social justice.

Pan-American feminism was also an outgrowth of the US suffrage movement. In 1928, US and Cuban feminists created the Inter-American Commission of Women, the first intergovernmental organization in the world. Initially led by National Woman’s Party veteran Doris Stevens, the commission forced an international treaty for women’s civil and political equal right into Pan-American and League of Nations congresses.

A heterogeneous group of Latin American feminists, however, also recognized continuing efforts of U.S. women to dominate the movement and developed a distinctive anti-imperialist Pan-Hispanic feminism that included but did not focus exclusively on the vote. Asserting their own leadership over Pan-American feminism, they called for derechos humanos, which implied women’s political, civil, social, and economic rights alongside anti-imperialism and anti-fascism.

At the 1945 San Francisco meeting that created the United Nations, Latin American female delegates, led by Brazilian feminist Bertha Lutz, drew on this movement to push women’s rights into the U.N. Charter and propose what became the U.N. Commission on the Status of Women. In the wake of these events, numerous Latin American countries passed woman suffrage.

Women from the global south continued to pioneer international feminism in the postwar years by pushing for inclusion of women’s rights in human rights treaties and linking women’s rights to decolonization movements.

Hansa Mehta from India, one of the two women on the commission drafting the 1948 U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Eleanor Roosevelt was the other), was responsible for Article 1’s reading: “All human beings are born free and equal” rather than “All men are born free and equal.”

Feminist activism from the global south swelled during the U.N. Decade for Women from 1975 to 1985. This movement was partly responsible for the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), an international treaty of women’s rights, adopted in 1979 by the U.N. General Assembly.

Article 3 demands basic human rights and fundamental freedoms for women “on a basis of equality with men” in “political, social, economic, and cultural fields.” Since its institution in 1981, it has been ratified by 189 countries, although not by the United States.

Meanwhile, U.S. women’s global activism has never abated, and the transnational legacies of the suffrage movement are evident in U.S. women’s ongoing quests for full citizenship today. Then as now, fights for women’s rights are connected to global movements for human rights—for immigrant, racial, labor, and feminist justice.

Chilean feminists rally during Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship (1973-1990).

The transnational history of the women’s suffrage movement shows us that activists and movements outside the United States, and a broad range of diverse and international goals, were critical to organizing for that right deemed so quintessentially American—the right to vote. It reminds us how much we in the United States have to learn from feminist struggles around the world.

Note:

This article originally appeared in a slightly different form as “The International History of the US Suffrage Movement” in the series, 19th Amendment and Women's Access to the Vote Across America, edited by Tamara Gaskell and published online in 2019 by the U.S. National Park Service in cooperation with the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers.

Read more: The Equal Rights Amendment Then and Now; International Women's Day; Women and American Politics; Domestic Violence; The Women’s March on Washington; Elizabeth Cady Stanton; The Real Marriage Revolution; Same-Sex Marriage; Women’s Struggles in Zimbabwe; Feminism in Egypt; and Women’s Rights in Afghanistan.

Listen more: The Long History of #MeToo; The Equal Rights Amendment; Women in American Politics; Violence Against Women; Reproductive Rights and Reproductive Justice; Same-Sex Marriage; Abortion in Europe and America; and Women in the Mideast and North Africa

Watch more: International Women's Day; Elizabeth Cady Stanton

And here’s a lesson plan based on this article: Are Women People?

Anderson, Bonnie S. Joyous Greetings: The First International Women’s Movement, 1830–1860. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Blain, Keisha N. Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Daley, Caroline and Melanie Nolan, eds., Suffrage and Beyond: International Feminist Perspectives. New York: New York University Press, 1994.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020.

Jones, Martha S. Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. New York: Basic Books, 2020.

McFadden, Margaret H. Golden Cables of Sympathy: The Transatlantic Sources of Nineteenth-Century Feminism. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

Roesch Wagner, Sally and Jeanne Shenandoah. Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Influence on Early American Feminists. Summertown, TN: Native Voices, 2001.

Rupp, Leila J. Worlds of Women: The Making of an International Women’s Movement. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Marino, Katherine. Feminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights Movement. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2019.

Mickenberg, Julia. “Suffragettes and Soviets: American Feminists and the Specter of Revolutionary Russia.” Journal of American History 100, no. 4 (March 2014): 1021–1051.

Ruiz, Vicki L. “Class Acts: Latina Feminist Traditions, 1900–1930.” American Historical Review 121, no. 1 (February 2016): 1–16.

Sklar, Kathryn Kish and James Brewer Stewart, eds. Women’s Rights and Transatlantic Slavery in the Era of Emancipation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

Sneider, Allison L. Suffragists in an Imperial Age: U.S. Expansion and the Woman Question, 1870–1929. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Tyrrell, Ian. Woman’s World, Woman’s Empire: The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective, 1880–1930. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Ware, Susan. Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019.