Argentina’s struggle with cholera in the 19th century offers important insights for the COVID-19 world today, especially on the importance of strong, centralized public health responses and the debate over economic restrictions and disease control.

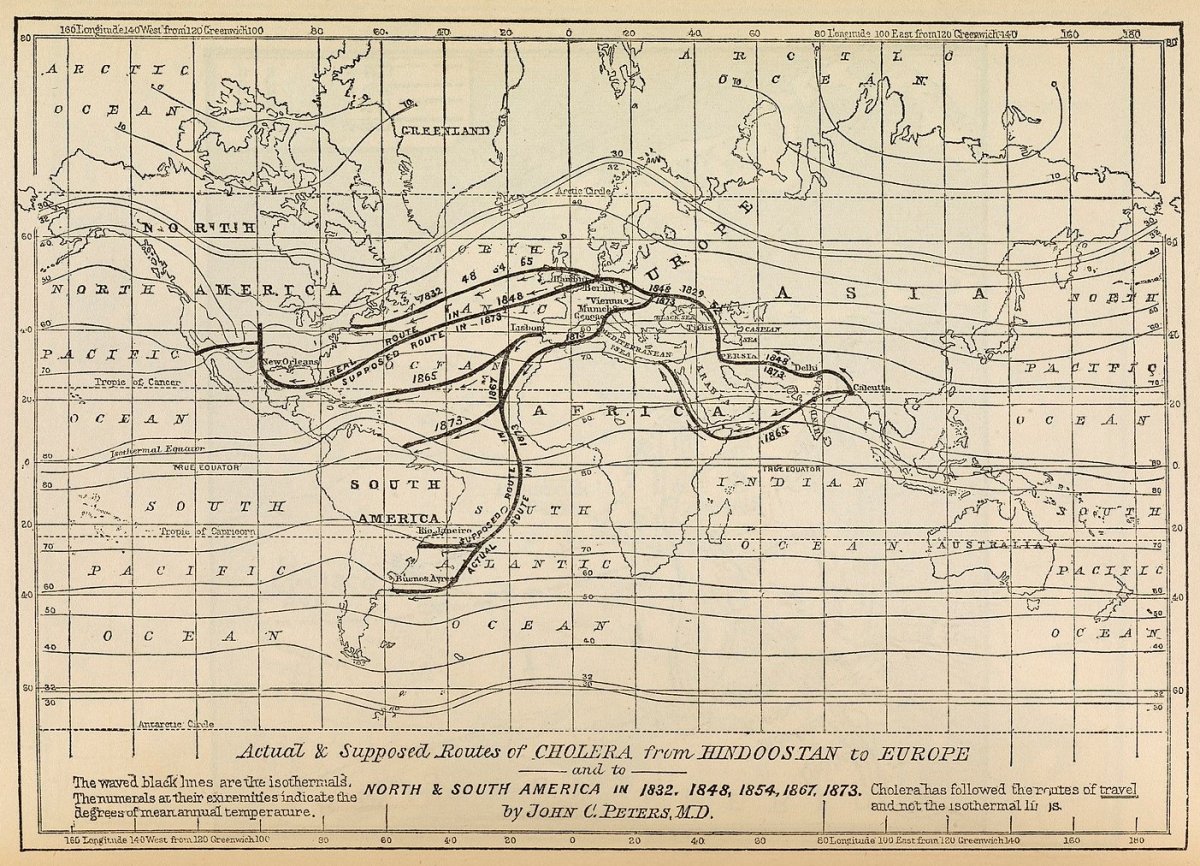

During the 19th century, no other disease united the globe more than cholera. Originating in South Asia, the disease spread through the linkages of trade and transportation, technological developments, and processes that imperialism and colonialism bore.

In a succession of pandemics that began in 1817 and continue to this day, cholera ravaged communities and strained political and economic orders throughout the globe.

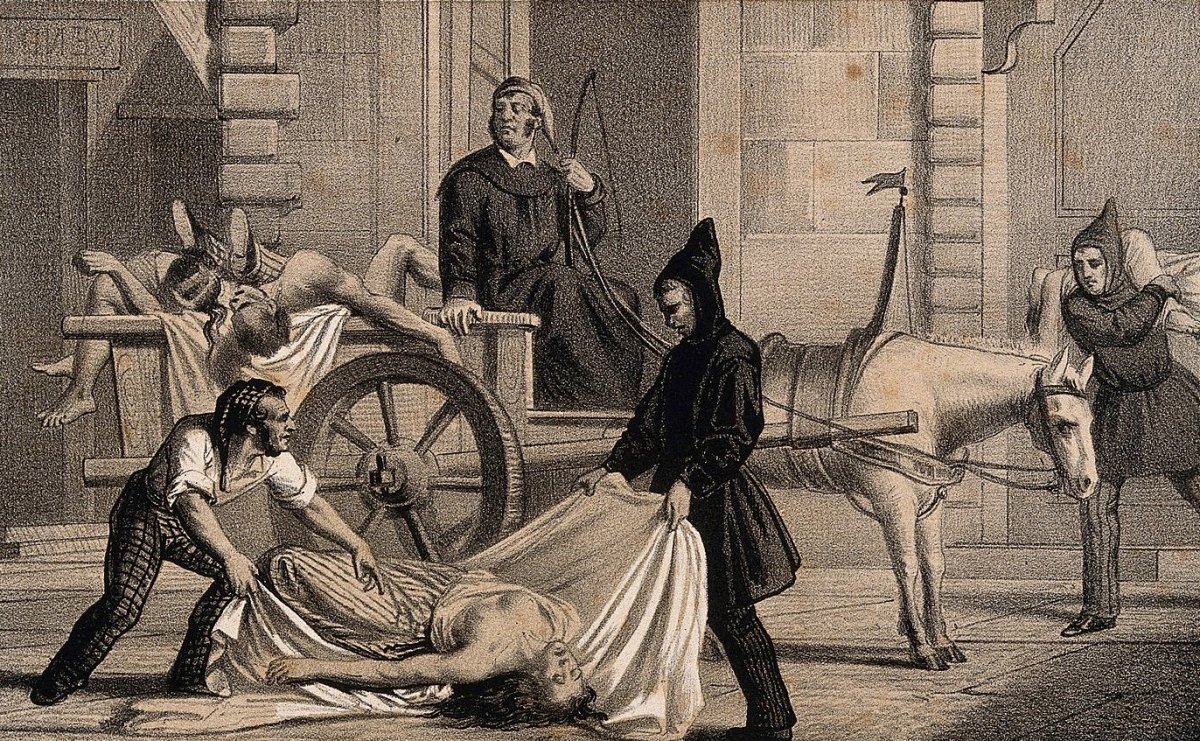

The unfortunate people who became infected with the gastrointestinal bacteria presented various symptoms: fevers, abdominal cramps, dehydration, nausea, the “bluing” of the skin, and violent bursts of diarrhea. Each time the body expelled its unwanted waste, it sent millions of bacteria into the water supply, creating a chain of infected and infectors.

By the turn of the 20th century, the threat of cholera became less pressing in much of the world. Public investment in municipal water systems and the creation of sanitation ordinances closed down cholera’s natural vector of contaminated water. Although much of the world has forgotten about cholera, the disease remains endemic in South Asia, areas of Africa, and, most recently, Haiti.

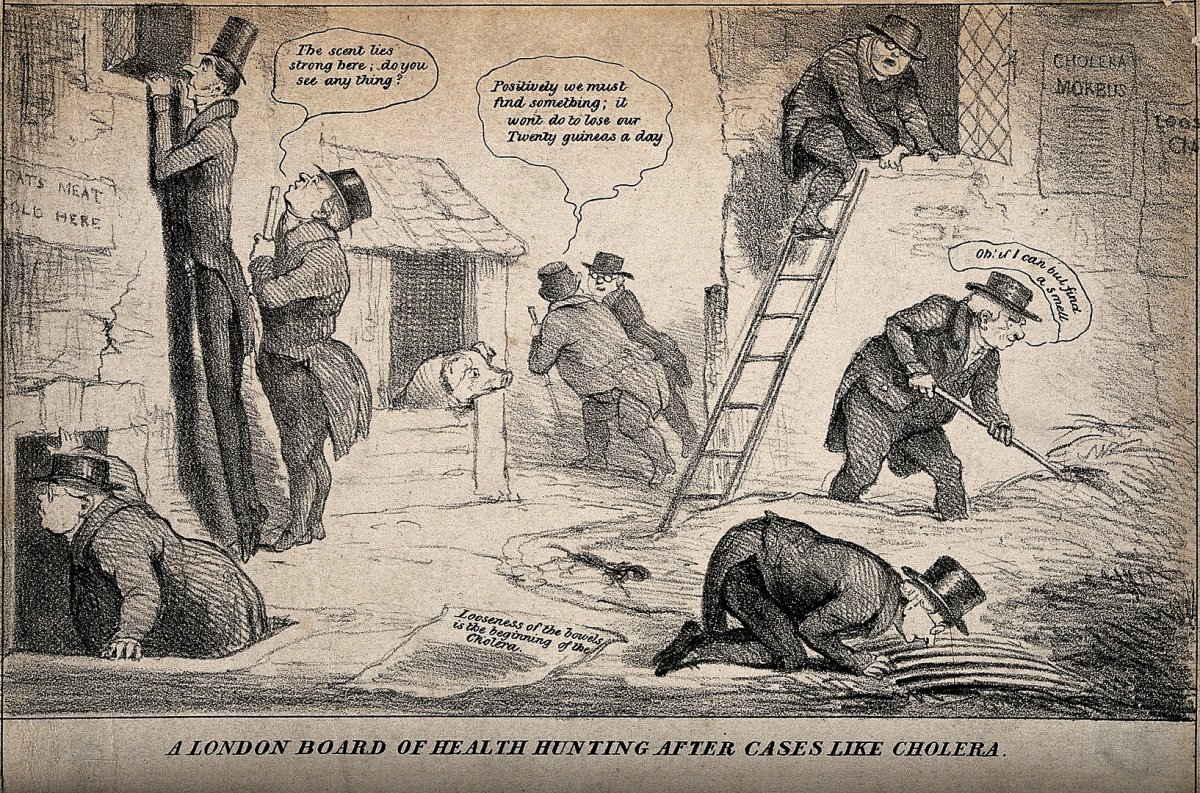

When cholera raged in the 19th century, the disease vexed medical specialists and other analysts. They questioned how a disease could move across the globe and how it adapted to new environments. There were virulent debates over how cholera spread between those who believed cholera was contagious and those who saw miasmas as its source.

For the former, cholera spread from person to person, which explained how it moved to new spaces, though they remained unsure about what exactly was spreading.

The latter relied on deeply entrenched beliefs that diseases spread through miasmas of odd smells, foods, purported immoral behaviors, or certain environments such as swamps, humidity, and heat. Indeed, even following the discovery of cholera’s bacterial origins (1854 and 1884), many remained convinced that cholera originated in miasmas.

That disagreement led to varying responses when cholera broke out. Many doctors advocated for quarantines and sanitary cordons that closed borders and suspended trade to slow the spread of disease. Other doctors and public officials opposed these measures on medical, economic, and moral grounds as they considered closed trade and borders the antithesis of modern and liberal nation-states.

Regardless of the response, it was impossible to separate governance, public health, and contagion from each other.

The medical historian Erwin Ackernecht proposed that a state’s political ideology significantly formed its approach to the contagion debate. He thus argued in the case of early 19th-century Europe that those anti-liberal states that believed disease to be contagious practiced strict sanitary cordons, quarantines, and general closures to protect home industries.

On the other hand, liberal states emphasized anticontagion practices. They endeavored to keep borders and trade open, promoted notions of personal freedoms, and provided a basis for hygiene-based interventions.

However, the response of most states was a combination of both methods. They tended to be pluralistic, eclectic, and malleable in their approaches to governance and contagion in response to numerous stimuli, such as the economy and the general uncertainty surrounding cholera.

One case study that encapsulates this tension is the 1886-87 cholera epidemic in Argentina.

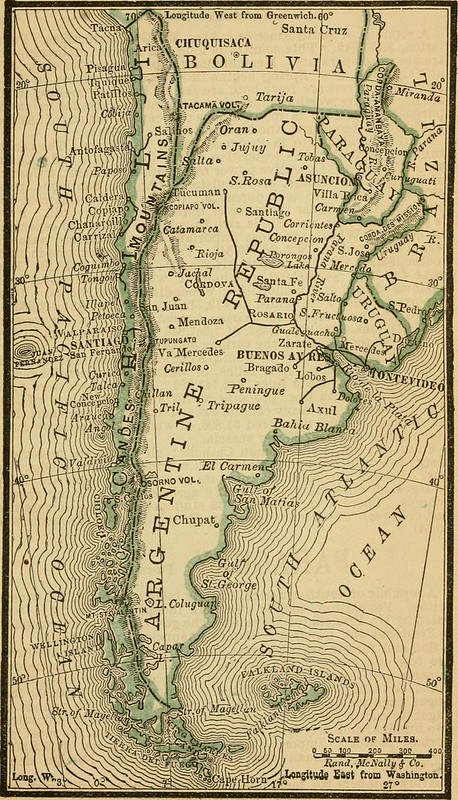

Between the 1860s and the 1910s, Argentina experienced four cholera epidemics. The appearance of cholera coincided with the end of decades of internal political conflicts between advocates of a centralized state and those opposed to it.

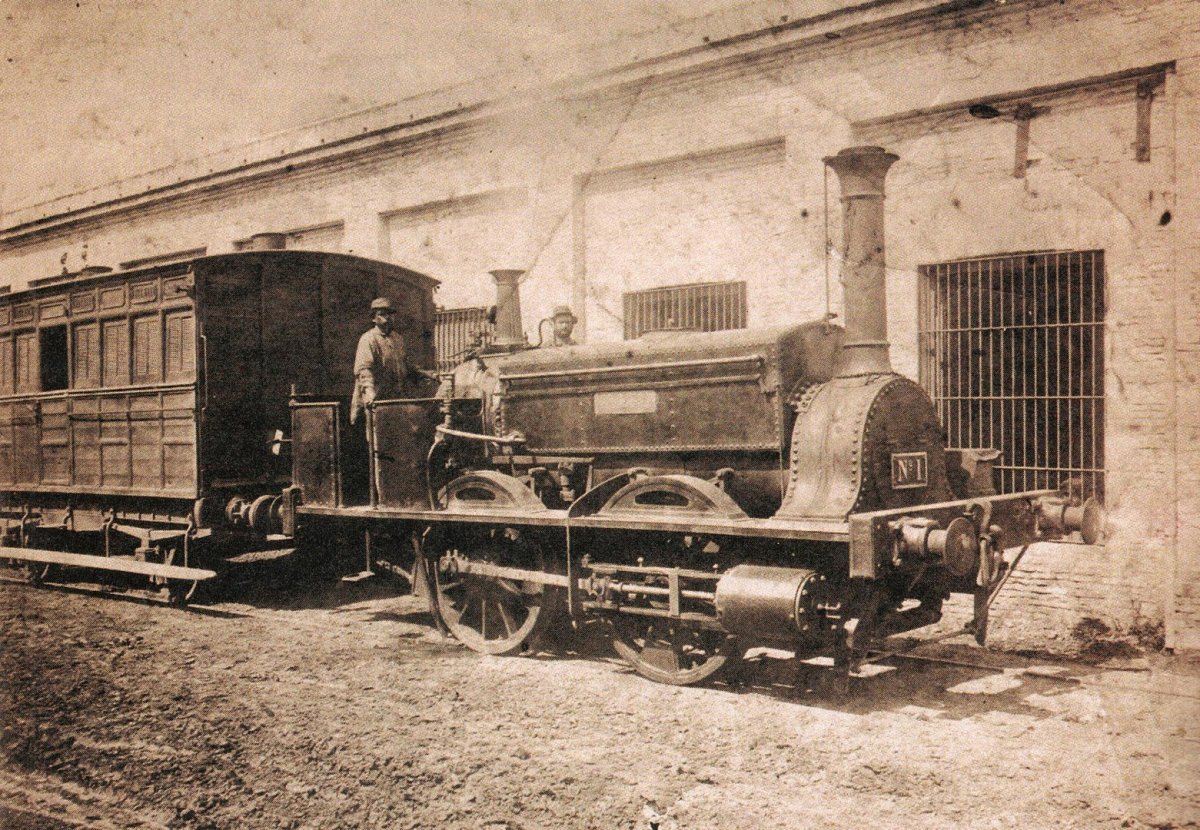

In the 1860s, the centralizers emerged victorious. For the remainder of the century the developing state undertook a project of interconnecting the nation through infrastructure and railroad projects and investing in regional economies. The state’s investment bolstered Argentina’s agricultural export economy and created conditions for a global disease to enter and spread.

In 1886, cholera arrived in Buenos Aires from Italy. As news broke of the epidemic, Brazil, a major trading partner, ceased importing goods from Argentina over fears of receiving cholera-contaminated goods, particularly beef jerky used to feed the local slave population.

The Brazilian government’s action caused an uproar within the Argentine beef industry and national government. Exporters banded together to demand the Argentine government put pressure on Brazilian officials to open their ports. On medical grounds, Argentine officials argued that recent research coming from the labs of Robert Koch in Germany showed cholera could not attach itself to food thus making to closure unnecessary.

However, the public and medical officials in Argentina had long connected an ever-evolving list of foods with cholera. Officials believed fruit, meat, and liquor made a person susceptible to or caused cholera, and recommended people avoid them at all cost.

So, while Argentine officials considered the closure an overreaction and inhumane, local doctors continued to warn Argentines about the dangers of meat. Brazil and Uruguay maintained their ports closed for the duration of the epidemic. Fortunately for exporters in Buenos Aires, the epidemic quickly moved from the port city and cemented itself in the northwest provinces.

Moreover, the Argentine government made no attempts to “stop the economy.” Indeed, many national officials considered cholera an unfortunate side-effect of integration into the global economy.

The contradictions over cholera also represent the systems of public health in Argentina. In the 1880s, Argentina’s medical system was decentralized and horizontally structured. As a result, an assortment of Offices of Public Assistance and Hygiene Commissions existed at the municipal and provincial levels throughout the nation. Meanwhile, a National Department of Hygiene did exist, but it had a limited presence beyond Buenos Aires.

It was not uncommon during the 1886-87 epidemic for public health protocols to change from province to province, and from city to city within a province, as each local medical cohort held their own views on cholera.

For instance, many provinces attempted to erect a sanitary cordon based on the medical premise that cholera spread human to human. Although the Argentine state succeeded in blocking these plans, the cordon debate opened a discussion on the extent of provincial autonomy and the powers of the executive branch in Argentina’s constitution. Following the epidemic, state and provinces came together to establish protocols for future epidemics.

These debates over public health, political powers, and economic structures have not been confined just to the 1800s, to cholera, and to the era before the wide acceptance of bacteriology. Indeed, there are parallels between cholera in 19th-century Argentina and Covid-19 in the United States and Argentina today.

Medical and administrative uncertainty dominated both. At first, some people in the United States believed COVID was a mild flu that easily passed and only affected the elderly. In the absence of a strong, centralized response to the pandemic, like Argentina in the 1880s, each U.S. state has followed its own approach to “reopening the economy” in terms of “phases.”

In some states, schools have reopened, face masks are optional, and people congregate. In other states, an entire generation is experiencing school online, face masks are required to enter any public space, and many venues cap the number of people inside. Nonetheless, the disease continues to spread, the public argues over the severity of the pandemic and calls for the economy to reopen, and society pines for a vaccine.

Things have not fared much better in Argentina as the pandemic has merged with the nation’s historically complicated economic conditions. Like the rest of the world, Argentina experienced the initial outbreak from March to June of 2020 and it seemed as though conditions were improving and life returning to some level of normalcy.

However, in October, cases began to rise uncontrollably in Buenos Aires and the provinces. Simultaneously, the new Left-Peronist government of President Alberto Fernández and Vice-President (former President) Cristina Fernández de Kirchner attempted to wrangle the continuing inflation that has become synonymous with the Argentine economy.

Indeed, between January and November 2020, the Argentine Peso devalued from 59.84 to 79.56 equal to 1 USD. However, as observers of Argentina know well, the true indicator of inflation is the valuation of the dolar blue, the black market exchange rate, which currently sits at 160 to 1 with all signs leading to a continued devaluation.

Beyond the exchange rate, the pandemic continues to hurt the Argentine economy. Since 2018, Argentina witnessed an uptick in the closure of small businesses and COVID-19 accelerated the process. At a higher level, many international corporations have also followed suit and left Argentina, citing pre-existing labor-state-corporation relations and worsening economic conditions under the pandemic.

Whether it be the 1880s or today, it is difficult to separate an epidemic from the complex political and economic contexts in which the disease appears.