Most of us probably don't see the thousands of motorcyclists who roar into Sturgis, South Dakota each year as avatars for the murkier world of high finance, tax avoidance, and neoliberal economic policies. But as historian Catherine McNicol Stock writes, South Dakota reinvented itself exactly in these directions, and those Harley-riding bikers who trash the town of Sturgis each year personify those economic forces at work.

In October 2021, South Dakota—long discounted as “fly-over country”—had a national moment. The Washington Post published the Pandora Papers, revealing that over $360 billion of secret wealth was stashed in 80 trusts established in a state with fewer than a million people. South Dakota, the stories revealed, had become the “Cayman Islands of the Heartland.”

As unlikely as it might seem, South Dakota provides one of the best places in the United States to examine the consequences of neoliberalism and its close cousin, fiscal conservatism. These terms describe a set of policies that have prioritized an unregulated market, small government, and reduced social spending, all at the expense of public control and the commonweal around the globe for the past half-century. These policies have made the rich much, much richer while leaving the rest to struggle.

South Dakota, for example, has no personal or corporate tax; its richest resident, T. Denny Sanford, is worth over $3 billion. Meanwhile, two of South Dakota’s counties are among the five poorest in the nation, and teachers’ salaries rank 49th nationally.

An event in December 2021 in Sioux Falls went viral when teachers at a minor league hockey game scrambled on their hands and knees to collect 5,000 individual dollar bills tossed on the ice. They could use the dollars they collected for classroom expenses.

Situations like this have been created all over the globe. South Dakota is not only a microcosm of neoliberal policies but a useful case study of how we got to this point in the first place.

From Farms to Finance

South Dakota has not always been like this. Even before it became a state in 1889, some South Dakota politicians—including those who found a home in the progressive wing of the Republican party—opposed “bigness” in all forms and feared the corrupting influence of wealth on politicians, the public, and individuals alike.

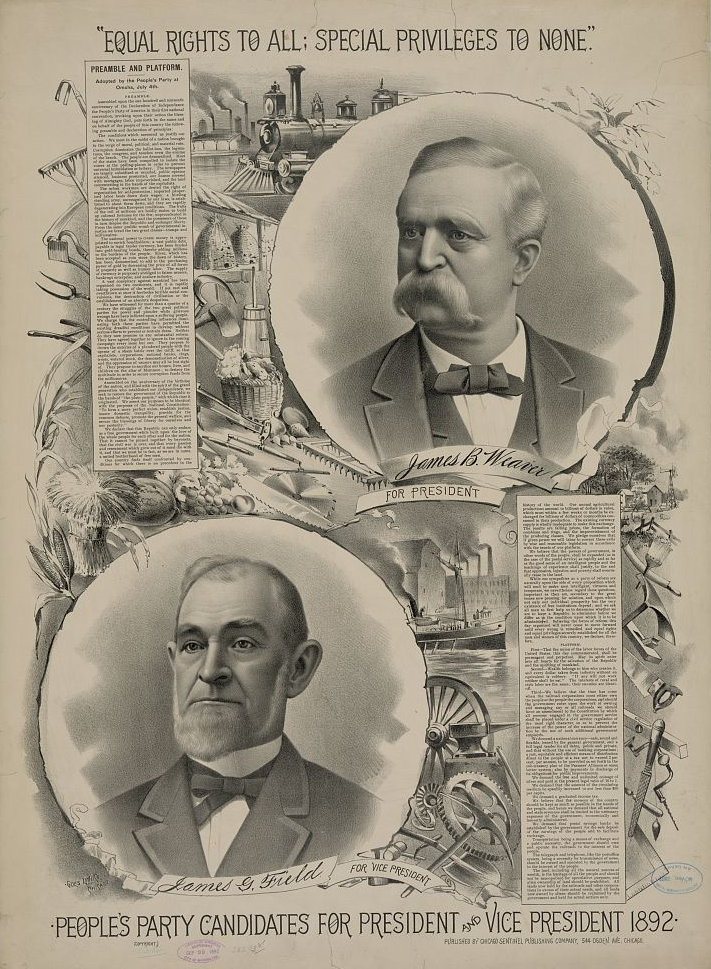

In 1892, South Dakotan Henry Loucks chaired the famed Omaha Convention at which the newly organized Populist Party proposed government ownership of railroads, loans and other supports for agriculture, and collective bargaining for labor. South Dakotans elected a Populist Senator, Governor, and two Congressmen. They also made sure direct democracy could thrive back home, being among the first states to enact the initiative and referendum, allowing citizens to bring a law directly to a vote.

Long after the Populist party met its end, some state politicians still supported federal spending: during the Great Depression, when a higher percentage of South Dakotans were on New Deal relief than in any other state; and decades later during the Farm Crisis of the 1980s. They believed, as the state motto still reads, that “under God, the people rule.”

Beginning in the 1970s, however, that motto became less and less true as the new conservative movement, often called “The New Right,” began changing South Dakota. Republican strategists like Richard Viguerie recognized that the growing influence of both military-affiliated and evangelical Christian voters rendered a sharp turn to the New Right likely.

Assisted by nationally funded Political Action Committees (PACs), they ended liberal Democratic Senator George McGovern’s career by contending that his views had strayed from “the South Dakota way of thinking.” They also put the state solidly—and seemingly permanently—in the win column for Ronald Reagan’s Republican Party.

Outside organizers would not be required to bring economic conservatism to the state, however. Facing the collapse of family farming, in late 1979 four-term governor William “Wild Bill” Janklow singlehandedly enticed Citibank’s credit card division to relocate to Sioux Falls, the state’s largest city. To do so, he invoked the state constitution’s “emergency clause” and forced a quick vote on ending state regulation of credit rates.

In 1983 he convinced legislators to change the laws regulating trusts to attract another sector of the financial services industry. Years later, Janklow boasted that—unlike previous governors—he hadn’t been “afraid of all these ogres from the big corporations or big America or big world.”

Even when it became apparent that South Dakota’s new laws enabled banks to charge ever-higher interest rates, bankrupting hundreds of thousands of financially vulnerable Americans, neither Janklow nor other conservative leaders acknowledged any downside to the new finance industry.

In a 2019 interview that raised the possibility the trusts were funded with money from illegal activity, University of South Dakota law professor Tom Simmons countered that finance was a “clean industry… [with] generally good-paying jobs.” Perhaps so, but the ability for lenders to charge unlimited interest hurt vulnerable South Dakotans too. Until 2014, pay day loans could charge up to 538% interest.

Despite the rhetoric that pits Wall Street against Main Street, South Dakota has transformed into a center of the finance economy, and as the Pandora Papers revealed, into a haven for wealth seeking a shelter from taxation.

What Bankers and Bikers Have in Common

Hundreds of miles from the booming financial district of Sioux Falls is a much smaller city—Sturgis, population 7,000—where local people have experienced the distinctly unclean consequences of South Dakota’s new economic thinking, even as they remain stalwart supporters of the modern GOP.

In the kind of local detail the Washington Post’s international investigation could not provide, the story of the people of Sturgis shows the costs of neoliberalism to ordinary men and women, including those who broadly support its free market principles.

Sturgis is home to the largest motorcycle rally in the world. Each August half a million or more bikers roar into town, bringing millions of dollars to state coffers through sales taxes. Not surprisingly, bikers also produce hundreds of tons of garbage, deafening noise, inflated prices, dangerously crowded roads, jam-packed emergency rooms, and spikes in crime, including sex trafficking.

In its first decades, the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally was neither the huge revenue generator nor the hypersexualized spectacle it is today. The rally’s founders focused on community-building as much as money-making. In 1939 Clarence “Pappy” Hoel and his private club, the Jackpine Gypsies, sought to bring bikers together for summer fun, races, and a ride in the beautiful Black Hills. The funds to cover each subsequent year’s expenses were collected as donations from the current year’s attendees.

And while the “West River” region of the state had long been known for a libertarian streak, Hoel recognized when national interest trumped individual concerns. During World War II, Hoel cancelled the rally. Furthermore, the rally did not acquire a reputation for bawdy activities even as it increased in size in the 1950s. For decades bikers felt perfectly comfortable joining locals at the evangelical Black Hills Passion Play performed nearby—and vice versa.

The 1960s and 1970s changed everything—from American politics to the culture of biking and, inevitably, the Sturgis Rally. In this “Easy Rider” era, bikers became associated with the counterculture, drug use, and sexual liberation.

Some private clubs morphed into violent gangs, and a few particularly chaotic and dangerous rallies convinced many residents in Sturgis that the event had to change or end. In 1981 and 1982, for example, townspeople were confronted by open sexual activity, public urination, arson, destruction of property, and attacks on local police.

Ten years later the rally had grown even bigger and even more out of control. In 1991 the city planned for 140,000 attendees but 400,000 arrived, including the Hells Angels and other outlaw clubs. Law enforcement wrote 2,143 warning tickets and 1,070 citations, making 202 arrests for driving under the influence and 78 for drug-related offenses. Eleven people died; two were murdered.

In response Sturgis residents organized using the traditional tools of direct democracy—petition drives, protests, meetings with members of their town councils, and votes. They demanded that rally organizers prioritize public safety—physical, moral, and spiritual safety—over everything else.

In 1981, the anti-rally forces were led by a local minister, Reverend Harold Fitch. Like the editor of a local paper, Fitch believed that “what [we] see on Main Street just reaffirms [the] belief that the whole damn country is on the downhill slide.”

Likewise, in 1991, 300 people signed a petition demanding that the rally change or be cancelled. One local man asked, “Is the rally really worth it? How many people in the Sturgis area think that the money that the rally brings in is worth the other things that the rally brings?”

The group published a statement of their four demands: three echoed Reverend Fitch’s public safety concerns—“the need for more garbage pickup,” “less pornography and obscenity,” and “less stress for the residents.” Only one—“a greater financial return to the community”—mentioned anything about profitability, and that mention suggested that the town wasn’t reaping the financial windfall they expected in return for hosting the bikers.

And yet at the same time, many local residents, 70% of whom voted for Reagan in 1980 and 1984, agreed with a primary tenet of New Right economics: low taxes. In 1981, Fitch and his forces petitioned for the right to hold a city-wide vote on continuing the rally. They won that right easily, but then lost the resulting vote by 88 ballots of more than 900 cast.

What made the difference?

A few things, no doubt, but Sturgis resident Leroy “Swede” Anderson found a statement from a local banker, Bruce Walker, most convincing. Walker said that if the rally ended, their taxes would increase. Another voter remarked, “That’s a pretty good statement, especially coming from a banker.”

South Dakotans had once viewed bankers with suspicion, but by 1981 the banker’s concerns carried more weight—just enough more—than the minister’s. It would not be the last time that the threat of a tax increase would convince South Dakotans, or Americans as a whole, to vote against programs that aimed to help the public at large.

Many locals also agreed with the Reagan-era idea that “government is the problem” and, by contrast, privatization must be the solution. They believed the unregulated market was most likely to develop innovative solutions to common problems. Former Chamber of Commerce president Dan Keppler described the new approach to improve the rally as “turning [the rally] over to free enterprise.”

To solve the problem of drunken disorder in the town square, for example, rally organizers encouraged a local entrepreneur, Rod Woodruff, to open a private campground, Buffalo Chip, east of town.

Likewise, when Native leaders protested the construction of an immense biker bar within a mile of Bear Butte, a federally protected religious site, local whites encouraged them to capitalize on the rally themselves, perhaps by promoting tourism on reservations, with the goal of someday buying the land back.

Most significantly, in 1991, people in Sturgis agreed to allow the Jackpine Gypsies and the town to create an entirely new governance structure, a corporation named Sturgis Races and Rally Inc. (SRR). The newly privatized management of the rally was sure to improve it, or so they hoped.

Few local people in the 1980s and 1990s likely anticipated that “free enterprise” solutions might over time increase the size, danger, and chaos of the rally. But it did exactly that and not by mistake.

The mission statement of the SRR said nothing about better sanitation or less obscenity. Instead, it aimed “to achieve a world premier event that will [bring] a significant, tangible, financial return to the residents of Sturgis and Meade County.” Thus, the SRR approved projects and expenditures that best fulfilled this goal.

While citizens had long complained of public nudity, for example, Woodruff countered with private nudity: all-nude beauty contests and wet t-shirt contests at Buffalo Chip and near-nude waitresses and strippers at bars and restaurants.

Finding this niche immensely profitable, other businesses followed suit. In 2009 Michael Ballard’s Full Throttle Saloon became the subject of its own reality-tv show, further amplifying the Vegas-inspired idea that “what happens in Sturgis stays in Sturgis.” Soon social media posts and boasts about sexual activities and enticements at the rally surpassed Reverend Fitch’s worst fears.

However it happened, one thing could not be denied: the money rolled in.

For the next two decades, cash poured into the region. The SRR licensed thousands of outside vendors, sought corporate sponsorships, and increased prices for tickets, rooms, and food. In 1991 the rally had just one corporate sponsor at $7,500. By 1995, it had 17, for a total of over $170,000. Over time, vendor licenses skyrocketed. In 2008 vendors made over $13 million in sales, and the state collected almost $900,000 in taxes.

In 2000, over 600,000 riders arrived for the 60th anniversary—50% more than just nine years earlier. The uptick in traffic on the state’s main interstate could be seen as far east as Sioux Falls, 350 miles away.

If the astonishing growth of the privatized rally surprised the residents of Sturgis, the problems that followed in its wake alarmed them.

The supersized rally did not positively impact all aspects of the local economy. When alligator meat vendors came from Louisiana to the campgrounds to sell their wares, for example, far fewer riders came into town to eat at local diners.

The rising costs associated with the rally impacted local people and visitors alike. Sky-high rents, for example, meant that some storefronts on Main Street lay vacant except for the weeks of the rally.

Nearby communities also struggled to maintain their older sense of community and identity beyond the rally. In 2021, a judge ruled that, despite covenant language to prevent it, homeowners in a new development in the Black Hills were free to open their homes to Airbnb guests in the summer months and, perhaps, never reside there themselves.

Women and girls found that the size and reputation of the rally could pose personal safety problems. One local blogger, Mandy Foster, did not hold back about “why I hate the rally.” Far worse than the 700 pounds of trash left behind was the constant sexualization of women, whether stripping, bartending, taking orders at McDonalds, or just walking around.

Foster knew some local women were comfortable commodifying their bodies to make some extra cash. She was most assuredly not: “I guess the only way I will ever enjoy the rally is if I can capitalize on it, but if that involves dressing like a hooker and flirting with old men, I don’t think I will anytime soon.”

As if to underscore her point that the rally could be a dangerous time for local women, Mandy’s post drew a threatening and obscene comment: “What a whiny bitch. Get a life you fucking pussy, stop being a scrooge. Post a picture of your face, I'll be sure to say hello, fuckingpussy.”

Finally, the privatization of the Sturgis rally revealed, much like the trust industry, how the public sector in a neoliberal environment prioritizes actions that benefit corporations and the wealthy rather than the public.

In this regard, “Wild Bill” Janklow—the same governor who brought Citibank and other financial services to Sioux Falls—was the “#1 biker in the state.” Janklow loved “all things motorized” and perhaps motorcycles most of all.

Having lived in the “West River” region for years, he attended the rally throughout the 1960s and 1970s, often with his son Russ—but never his wife—in tow. Throughout his years as governor, Janklow worked behind the scenes to promote the rally and support its newly corporatized management.

In fact, dozens of constituents routinely wrote to him each year with personal questions and concerns regarding the event. Of course, Janklow also used the rally as a political platform—a place to be seen and reinforce his “maverick” persona. He was hardly the last conservative to appear at Sturgis. John McCain, Sarah Palin, Mike Rounds, Tommy Thompson, and Kristi Noem all followed in his footsteps.

Janklow’s actions as governor—no matter which side of the Missouri River he was from—reinforced the priority of fiscal conservatism: profit above all else. When a member of the Jackpine Gypsies wrote to complain that the SRR no longer included club members in major decision-making and that its officials sometimes did not even answer their letters, Janklow replied with empathy—but not action.

When he learned that the founders of the Black Hills Passion Play asked that the rally switch its dates from August to September because they believed as many as 5,000 people had chosen not to see the play during the rally due to the “biker stereotype,” Janklow let the money do the talking. The rally made far more tax revenue for the region than the play: enough said.

By the time of Janklow’s resignation from office in 2003 (after he had run a red light, killing a motorcyclist), this trend of the public sector working to serve private interests had expanded beyond the governor’s mansion.

In 2015, the 43 residents of Buffalo Chip campground voted to become a “municipality,” able to get federal and state grants, sell liquor licenses, and collect taxes. They remained so until 2019, when the Fourth Circuit Court deemed 43 to be an insufficient number of residents to incorporate. Doing so, even temporarily, took authority away from Sturgis and cost it money, as it had to compete with Buffalo Chip for grants and other support.

A few people in Sturgis recognized perhaps the most profound consequence of neoliberal policies. They began to suspect that in the interest of keeping their taxes low, they had given up democratic control of the rally that bore the town’s name and still provided its marquee location.

Several times between 1981 and 2020, Sturgis residents used the traditional tools of direct democracy to reform the rally—or cancel it altogether. They believed they had succeeded in the 1980s and 1990s when the city devised a new corporate governance structure. They trusted it would make the rally safer and more profitable. Over time, however, they came to see that an organization structured to prioritize profit would neglect the public good (unless the “public good” was defined solely as making money).

Sturgis resident Roger Call wrote to the Meade County Times Tribune and accused local officials, in collaboration with the SRR, of siphoning off profits that should go to the town. “This whole SRR thing again is all about one thing, MONEY!!!” he said. “The taxpayers of Sturgis and of South Dakota are the true losers with this big hoax!” Another rider wrote simply, “SRR sucks!”

Even more residents saw that the traditional tools of direct democracy no longer effected change when the wealthy could afford to dodge their consequences.

In 2017 taxpayers voted down a special increase to pay for a six-mile road from I-90 to Buffalo Chip because it would bypass the city and decrease revenue. In response, Woodruff offered to pay the extra million dollars himself.

Private Profit vs. Public Health

As it did in many other places around the world, the Covid-19 pandemic cast a bright light on the costs of four decades of neoliberalism in South Dakota.

In spring 2020, more than half the residents of Sturgis surveyed wanted the town council to cancel the rally. They had the support of federal, state, and local health officials, who feared that hundreds of thousands of riders coming to the region to crowd, maskless, into bars would turn the rally into a super-spreader event.

But they did not have the support of the people who could actually control the rally—the governor, the SRR, and the riders themselves. Governor Kristi Noem appeared on FOX News to welcome riders to the “freedom” state. Some riders announced on social media that they were “still going. Cancelled or not.”

Finally, it was unclear whether the town council had the authority to cancel the rally or the funds to defend their decision if they did. Rushmore Photo and Gifts threatened to sue the city if the rally was cancelled. They knew beyond a doubt that the city did not “own” the rally. “You can’t cancel what you don’t own,” said rally organizer Randy Peterson in 2020. In the neoliberal South Dakota, the public could no longer be trusted with something as profitable as the rally.

In the end, the mayor and city manager sounded as defeated as the measure to cancel was. Holding the rally, according to city manager Daniel Ainslie, was “the best decision that was available to them.” In mayor Mark Carstensen’s words, the bikers were coming “no matter what.” He added, “I said back in March, would you like me to build a wall around the city, around South Dakota, because that is the only way we could stop them.”

Still concerned for public health and safety, however, Ainslie offered free grocery delivery so residents could simply stay at home. Of course, staying home and missing the chance to “capitalize” on the need for workers during the rally was not a choice for most residents. For them, Carstensen arranged for free testing.

When all was said and done, the only debate left in Sturgis was how many COVID cases and deaths across the country were tied to the rally: hundreds, or hundreds of thousands.

Despite the rampaging Delta variant and low rate of vaccination among South Dakotans and riders alike, no one attempted to stop the 2021 rally.

That was no surprise. Over 40 years of rallies, the residents of Sturgis had seen that venerating the free market and prioritizing profit sometimes meant sacrificing public health and safety. They had also learned they could no longer do anything about it.

But perhaps it was worth it. As the Sioux Falls Argus Leader reminded readers concerned about the uptick in COVID cases in the state in the wake of the rally, the visitors had added $1.8 million dollars in tax revenue to state and local coffers. South Dakota’s reputation as a state “free” from high taxes stayed secure.

Oliver Bullough, “The Great American Tax Haven: How the Super Rich Came to Love South Dakota,” The Guardian, November 14, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/14/the-great-american-tax-haven-why-the-super-rich-love-south-dakota-trust-laws.

Carl Edeburn, Sturgis: The Story of the Rally (n.p.: Dimensions Press, 2003).

David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Daniel Krier and William J. Swart, NASCAR, Sturgis, and the New Economy of Spectacle (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018).

Randy D. McBee, Born to be Wild: The Rise of the American Motorcyclist (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2018)

Greg Miller, Debbie Cenzier, Peter Whoriskey, “Pandora Papers: Billions Hidden beyond Reach,” Washington Post, October 3, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/interactive/2021/pandora-papers-offshore-finance/.

Rick Perlstein, Reaganland: America’s Right Turn, 1976-1980 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2020).

Hal Rothman, Devil’s Bargain: Tourism in the 20th Century West (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2000).

Herbert S. Schell and John E. Miller, History of South Dakota (Pierre: South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2004).

Catherine McNicol Stock, Nuclear Country: The Making of the Rural New Right (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).