When Donald Trump announced early in 2025 that the United States would withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO) he threatened to undo over a century's worth of efforts to build a global system to protect public health. In this article, historian Jim Harris traces the roots of the WHO back into the 19th century and examines how public health and foreign policy have often gone hand-in-hand.

On April 7, 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) celebrated its 75th birthday. On this auspicious occasion, Ethiopian Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus reflected: “We have a lot to be proud of over the past 75 years, but it’s not the last 75 years that matters – it’s the next 75. We learn the lessons of the past so we can apply them in the future.”

Ghebreyesus is correct. We can learn much from the history of the WHO about the importance of international cooperation in the promotion of public health. But the lesson of that recent history has not been taken to heart in the United States.

Laying the Foundation

The roots of the WHO can be traced back to the 19th century and the first European International Sanitary Conference in Paris in 1851. Though the conference focused solely on mitigating cholera—about which little was then known and on which no political consensus could be reached—this meeting laid an important foundation for future international cooperation.

Subsequent conferences widened the scope of public health while maintaining a focus on controlling disease.

For example, the 10th conference in 1897 concerned preventing the spread of plague into Europe during the third plague pandemic. Into the first decades of the 20th century, the International Sanitary Conferences expanded discussions about the response to other infectious diseases such as yellow fever, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever.

European conferences created a model for other regions of the world to follow. The first international public health organization was formed in the Americas. The Pan American Sanitary Bureau (eventually renamed the Pan American Health Organization, or PAHO) was established in 1902 and administered through the U.S. Surgeon General’s office.

Its original member states included Brazil, Nicaragua, Peru, the United States, and Venezuela. Its mission was “to consider and report on the new methods of establishing and maintaining health regulations in trade between the various countries” and then “to formulate sanitary agreements and regulations and to periodically hold health conventions.” The PAHO still exists today as one of six regional working groups within the WHO.

In Europe, L’Office International d’Hygiene Publique (OIPH) was established in 1907 to standardize quarantine practices, gather and share epidemiological data on infectious diseases, and offer recommendations on sanitation. The OIPH would later become a partner of the League of Nations Health Organization (LNHO) after World War I, which sought to “take steps in matters of international concern for the prevention and control of disease.”

While the United States never joined the League of Nations, U.S. medical experts routinely offered their advice to the LNHO. Between this informal relationship and its leadership in the Pan American Sanitary Bureau, the United States began to stake out its leading role in global public health campaigns from the early 20th century—an outsized role that would only increase in aftermath of the Second World War and through the Cold War.

Rising from the Ashes: The WHO is Born

The Second World War demonstrated that the League of Nations had failed, and from its ashes rose a new entity: The United Nations.

One of the promises underpinning the UN was greater international collaboration in public health. But what would such collaboration look like? It could not simply be the rebuilding of the LNHO, because of the United States’ lack of participation. The postwar world would have to build something new.

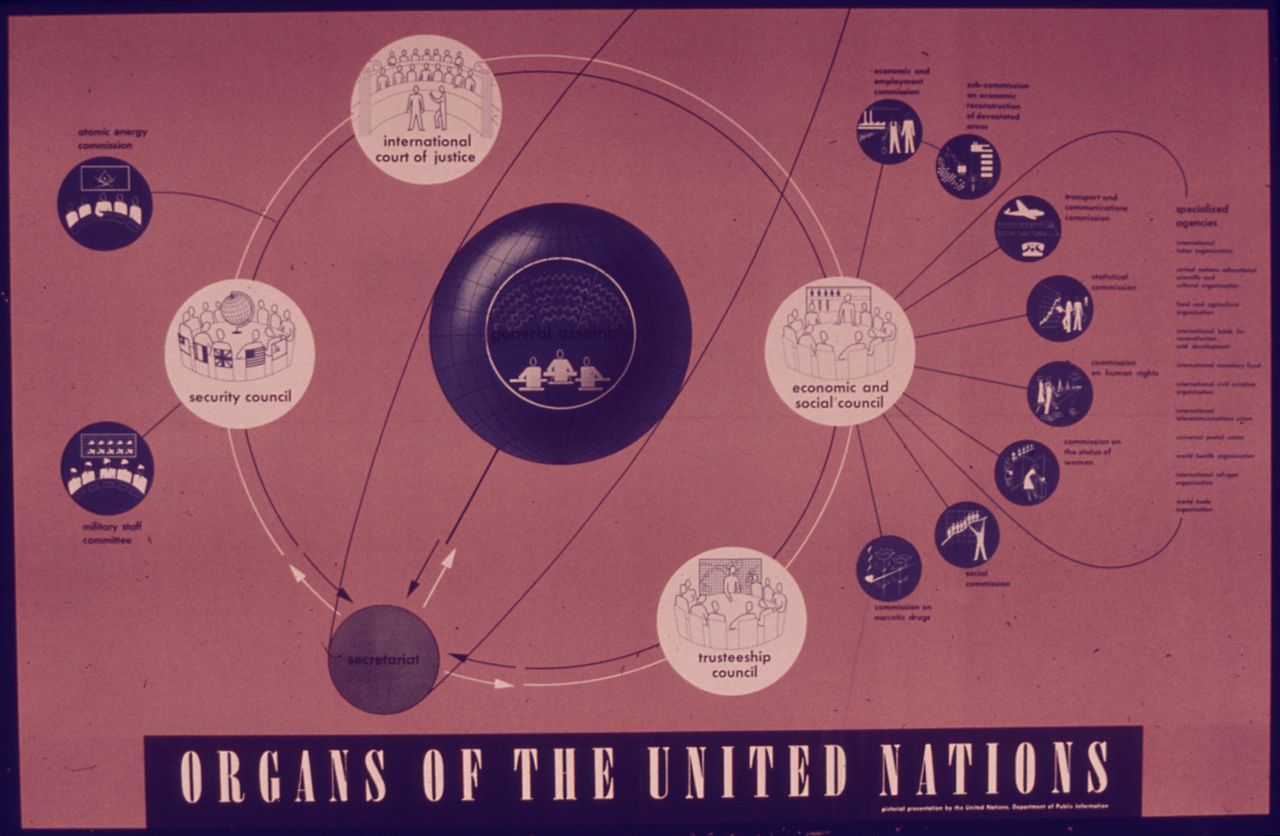

At the UN Conference on International Organization in 1945, the Brazilian and Chinese delegations jointly proposed that a new international health organization should be a “major aim” of the United Nations. An International Health Conference in 1946 established that a World Health Organization (WHO) would carry out this mission for the UN. Sixty-one states signed the WHO Constitution, which went into effect on April 7, 1948 (the origin of World Health Day).

The WHO’s mandate was “to act as the directing and coordinating authority on international health work.” It would absorb its predecessors (including the PAHO, OIHP, the LHNO) into one global organization, governed by a World Health Assembly (WHA) with representatives from all signing member states. Funds would be collected as dues from member states, based on their respective wealth and population.

Ambitious Goals and Major Milestones

U.S. and European foreign policy shaped the organization’s early work.

When the World Health Assembly first met in Geneva in 1948, it established priorities for the WHO: targeting malaria, tuberculosis, and venereal diseases, as well as promoting maternal and child health, sanitary engineering, and global nutrition.

But the WHO had a budget of only $5 million in 1948 (the equivalent of about $67.43 million in 2025) and a total staff of 200. These were lofty goals on a relatively shoestring budget and miniscule staff. Thus, by its own admission, the WHO had to make “painful choices” about its priorities.

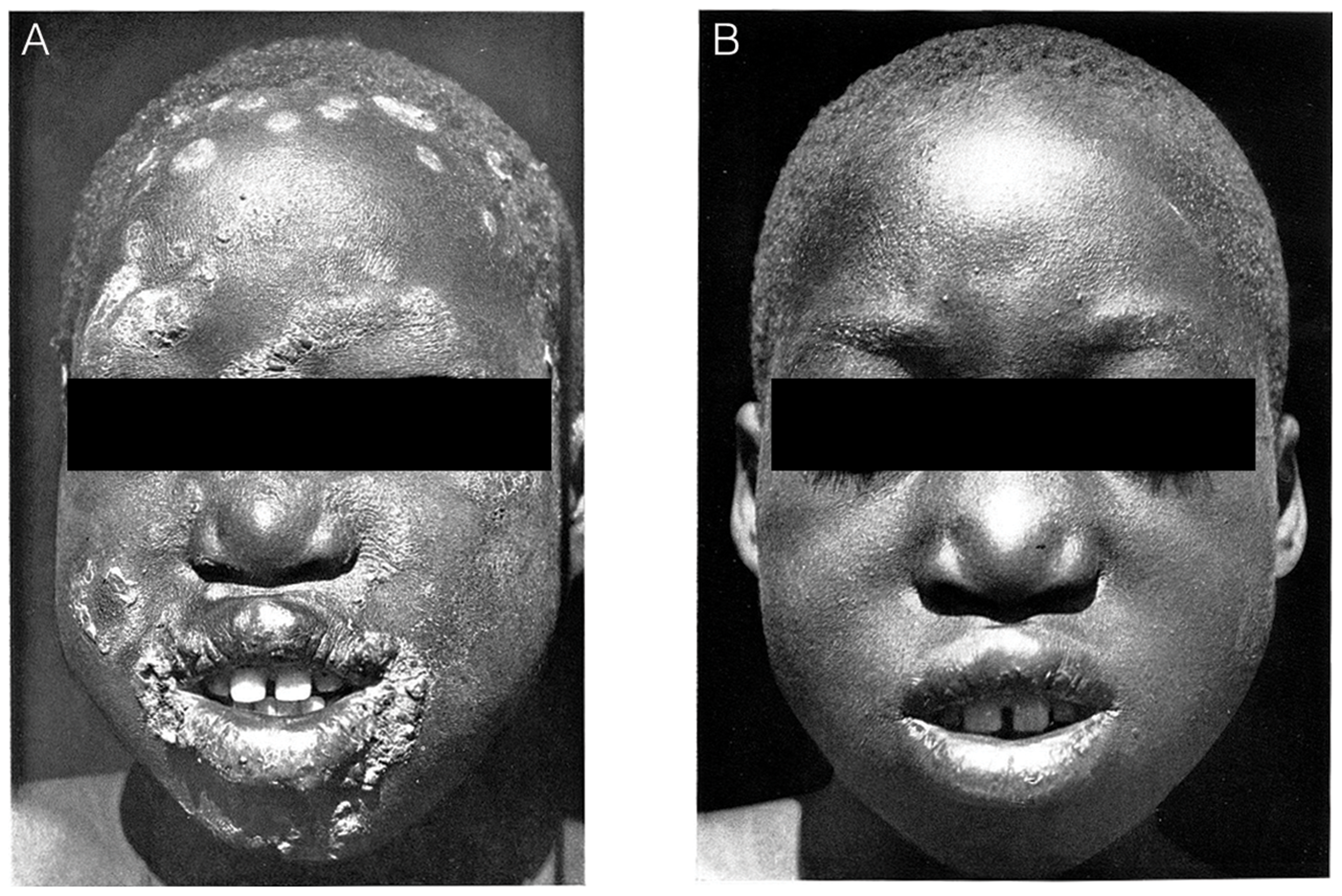

In its first decade, the WHO leadership decided to target yaws, a crippling genetic relative of syphilis that spread due to poor hygiene and particularly afflicted children. Yaws afflicted some 50 million people in 1948. While treatment was relatively easy to provide, the cost of multiple penicillin injections was too expensive for many poorer countries to absorb, making treatment inaccessible for many.

The WHO directed research trying to simplify the treatment into a single long-acting injection. The WHO chose not to do the “bench work,” but, in the words of their 1988 report, Four Decades of Achievement: Highlights of the Work of WHO, “would become the coordinating force behind a network of first-class scientists and national laboratories chosen for their technical excellence and pledged to work, through WHO, for the benefit of all humanity.”

Thus, yaws set the stage for the WHO to standardize the production of biologics and other pharmaceutical products, an ongoing international role that continues to this day.

The WHO then took up the more difficult task of publicizing the new treatment and providing training and funding to member nations. With its tiny staff, the WHO could not do the fieldwork alone but was highly effective at establishing partnerships—both with local medical practitioners and other international aid organizations like UNICEF, which, in the case of yaws, directed funds to supplies and services while the WHO focused on scientific research.

By the early 1960s, 49 countries had taken advantage of support from the WHO, and global cases of yaws were reduced to nearly zero.

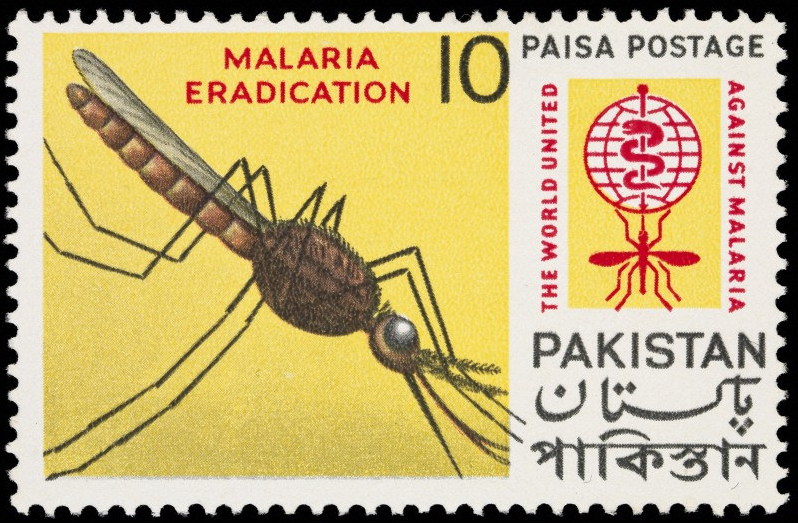

Building on its success against yaws, WHO leadership believed that medical science could eradicate (or at least substantially reduce) other diseases worldwide. In 1955, leadership set their sights on a much bigger threat: malaria.

Early 20th-century efforts to control malaria focused on draining marshes and swamps, spraying the insecticide Paris green, greater (and expensive) distribution of quinine, and protecting human homes with nets and screens.

After the Second World War, PAHO/WHO regional director for the Americas Fred Soper became convinced that malaria eradication through the extensive use of pesticides was not only conceivable, but superior to other malaria control measures that were, at best, irregular and expensive.

Efforts by the PAHO in the Americas in 1954 would lay a foundation for the WHO to build upon in a global campaign against malaria: through the use and misuse of DDT with all its associated environmental consequences.

The WHO surveyed malaria-endemic countries in the late 1950s and concluded that malaria was “the most expensive disease” (in terms of mitigation and lost earnings from illness), making the high cost of an eradication campaign (estimated at $114 million) worthwhile over the long term.

By the early 1960s, most developing countries agreed to participate in the WHO’s campaign. At-risk populations for malaria shrank by about 74% from 1955 to 1965. The WHO successfully eliminated malaria from about two dozen countries, but the disease remained an unresolved threat. In 1969, the costly campaign was abandoned.

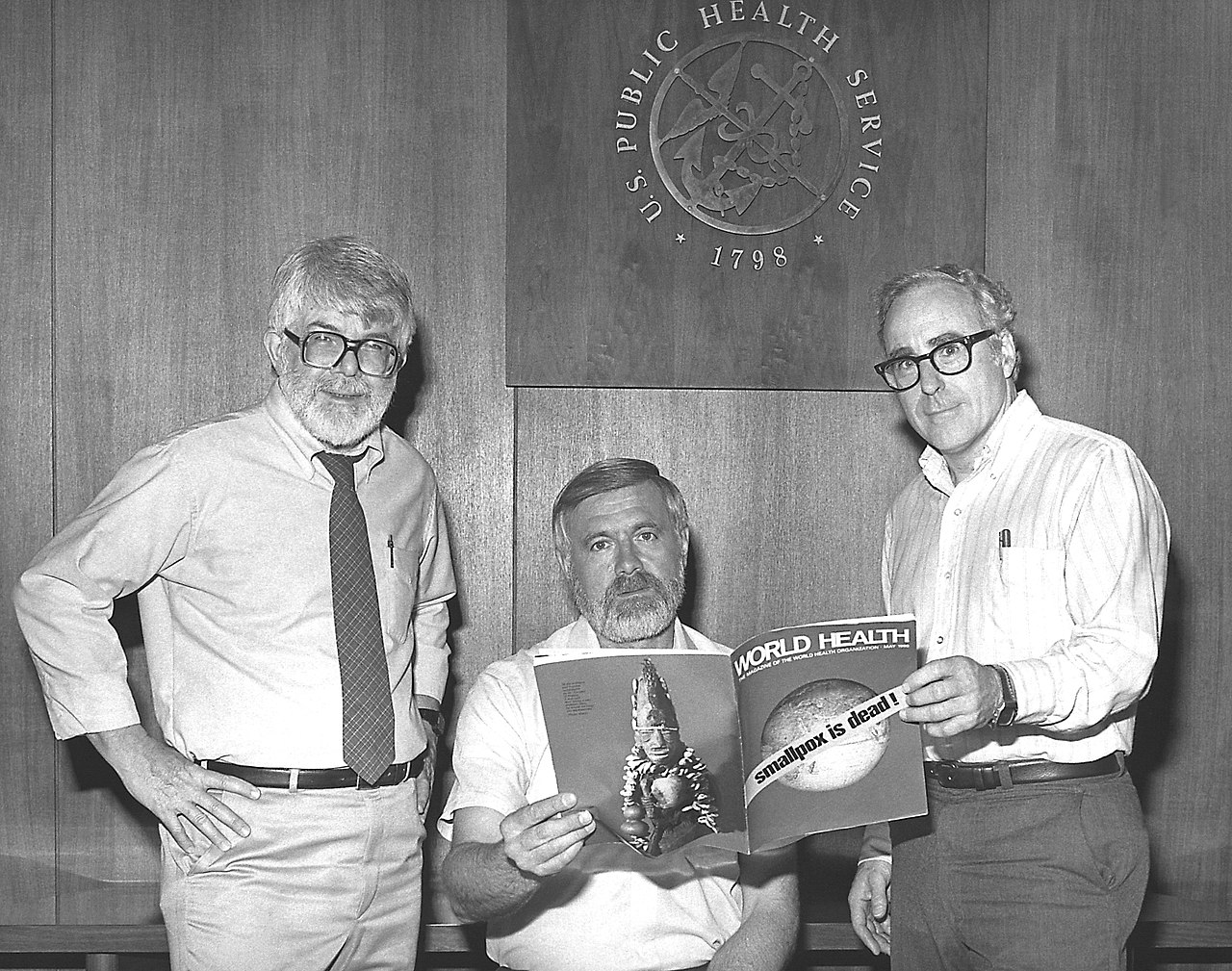

While efforts to completely eradicate malaria failed, the campaign established the precedent for, arguably, the WHO’s most important achievement: the successful eradication of smallpox in 1980. Through the leadership of Donald Henderson, the United States played a central role in the WHO’s smallpox eradication campaign.

The impacts of smallpox eradication were enormous. Smallpox endemic regions were spending hundreds of millions of dollars per year on vaccination/revaccination campaigns and establishing cordons sanitaires. The WHO estimated that the 13-year Intensified Smallpox Eradication Programme cost $330 million but saved $1 billion annually in returns.

Beyond cost savings, the success of the program revealed the importance of global cooperation in the promotion of public health: it relied on domestic vaccination and surveillance teams in smallpox-endemic countries, supported by international technical and material support (especially from the United States and the Soviet Union) in the form of vaccines, materials, and money.

Finally, smallpox eradication revealed the importance of vaccination more broadly. Thus, in 1974, the WHO launched the Expanded Programme on Immunization, which tried to raise awareness about dangerously low vaccination rates in developing countries with vaccination rates (as low as 5%) against deadly but vaccine-preventable diseases (diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, polio, measles, and tuberculosis).

Through its partnership with UNICEF, the WHO also developed the technological means to extend the reach of vaccination efforts, building out “cold chain” infrastructures to keep vaccines stable and potent from manufacture to injection, ranging from temperature monitors to portable iceboxes.

Cold War Contexts and Decolonial Challenges

The World Health Assembly, the governing body for the WHO, sought to be apolitical. WHO leadership also sought to avoid entering binding, multilateral agreements, and instead focus on technical advice and disease-specific assistance to countries in need. But the origins of the organization during the early Cold War made it impossible to be truly politically neutral.

Debates about national health services paid limited attention to the idea of “socialized medicine” that would make healthcare a basic human right and establish medical services available to all—much to the frustration of the Soviet Union, resulting in a brief Soviet withdrawal from the WHO in the early 1950s.

Meanwhile, the WHO’s agenda shifted ever closer toward U.S. foreign policy objectives (including the containment of communism) as the WHO became increasingly reliant on U.S. funding.

Decolonization also created new challenges for global health. Former imperial powers offered promises to care for the health of former colonial territories, but these promises were irregularly kept. So, when newly independent nation-states became voting members of the World Health Assembly, they brought new priorities to the table, including developing their own medical independence, ideally with the support of the WHO.

Nevertheless, the African regional office of the WHO was the slowest to develop because WHO leadership was dominated by the influence of Western Europe and North America who found the region to be “lacking” the necessary health infrastructure. This made the development of the region in the early 1950s/60s even more important to the work of the WHO.

To highlight one notable success story, we might look at the example of the Democratic Republic of Congo. In July 1960, the Secretary-General of the UN called upon the WHO to supply emergency assistance to the newly independent Democratic Republic of Congo. 761 foreign doctors left the country during decolonization, leaving the newly independent nation without a single medically qualified Congolese physician.

The WHO response was rapid and consequential. A medical team was dispatched to Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) to develop a plan of action to establish both a short-term system of emergency medical care and a longer-term training of Congolese medical personnel.

Within a month, the WHO, in collaboration with the Red Cross, established 33 emergency teams and recruited 200 medical staff. Meanwhile, the WHO established a fellowship to send 140 Congolese abroad for full medical training to lay the foundation for an independent, self-sustaining Congolese public health infrastructure. By 1967, the WHO had succeeded.

Training doctors in the newly independent Democratic Republic of the Congo was exemplary of another important aim of the WHO: collaborating with health educators to offer fellowships for advanced training in health services, controlling infectious diseases, and in some cases (especially for newly independent countries in Africa) a full medical education. By 1987, some 90,000 individuals received some form of WHO fellowship.

Alma-Ata and AIDS

Beginning in the 1970s, the WHO began to shift its approach to global health in a new direction: building a broader foundation of Primary Health Care (PHC) rather than its earlier, narrower focus on technocratic interventions in response to disease outbreaks.

PHC emphasized collaboration, preventive medicine, and focused on promoting self-care. In 1973, newly elected Director-General Halfdan Mahler would make PHC and targeting the social determinants of health a new focus for the WHO.

A joint report between WHO and UNICEF published in 1975 reported that poverty, squalor, and lack of education were among the leading causes of illness in the developing world. Mitigating these risk factors would take far more than technological interventions. Thus, in 1976, the World Health Assembly adopted its new goal of “Health for All by 2000”—a goal that emphasized the importance of global health equity and social justice rather than a target for an individual disease state.

Two years later, at an International Conference on Primary Health Care held in Alma-Ata, the capital of Kazakhstan (then part of the Soviet Union), the goals of PHC were debated and codified.

The Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 articulated Mahler’s vision for the future work of the WHO: “that health, which is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, is a fundamental human right and that the attainment of the highest possible level of health is a most important world-wide social goal.” Hailing from 134 countries and 67 international organizations, 3,000 delegates attended the meeting.

Efforts to provide basic health services brought the WHO into closer partnership with other international aid organizations like UNICEF and USAID. But the 1980s also brought about new challenges to the implementation of PHC.

First, the election of conservatives like President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, famous for their neoliberal economic policies that sought to limit government spending, weakened the financial backing for the WHO. Reagan emphasized, however problematically, his belief that trickle-down economics was the key to solving the world’s economic problems, including those that created threats to public health.

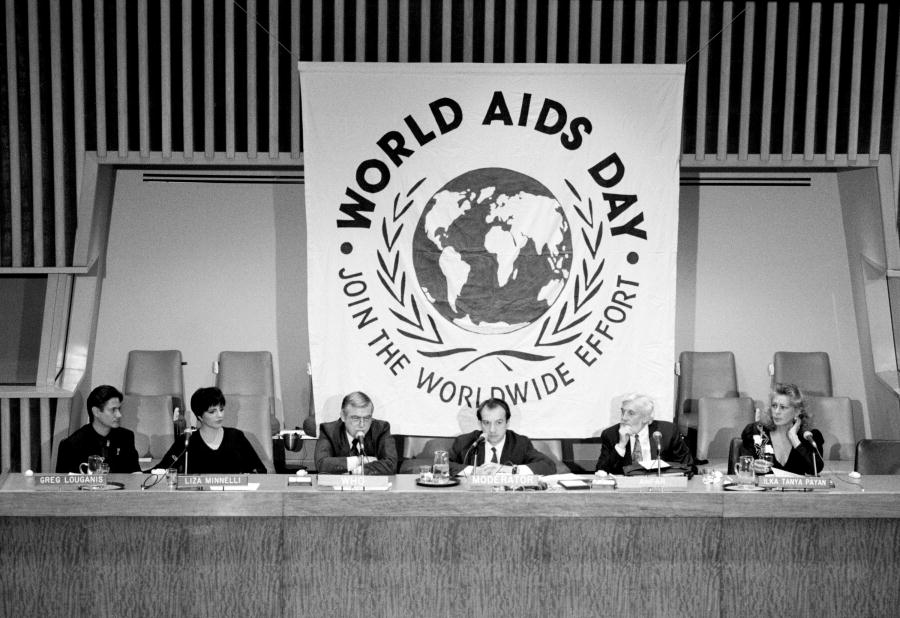

Second, the emergence of the AIDS crisis, which the Reagan administration willfully ignored, forced the WHO to pivot back to its old ways of focusing on biomedical interventions targeting specific diseases rather than preventative health care. Yet, like the Reagan administration, the WHO response to the AIDS crisis missed the mark: it was slow and indecisive at first. WHO leadership did not pass a resolution to combat AIDS until 1986.

However, once the WHO’s Global Program on AIDS (GPA) was launched, it grew rapidly under the leadership of the American physician Jonathan Mann. Between 1986 and 1989 the budget for the GPA expanded from $5 million to $60 million, with most of the funding coming from private donors and bilateral agencies.

Mann believed that disease outbreaks were “not only biological threats but serious challenges to human rights.” Thus, efforts to combat HIV/AIDS, a disease infamously stigmatized, fell well within the mission of the WHO to promote health care as a basic human right.

After Mahler retired as director-general of the WHO in 1988, however, his successor Hiroshi Nakajima was less supportive of Mann’s position. Nakajima believed that the GPA had become too big and rolled back the work Mann had done. Mann was forced to resign in 1990.

In the reorganization that followed, the WHO lost its leading role in combating HIV/AIDS to UNAIDS from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, when the WHO once again took a principal role in trying to increase global access to anti-retroviral treatments.

From the Age of Globalization into the 21st Century

As the Cold War was coming to an end, perceptions of the WHO changed—for the worse—as both “public and private interest groups began to attack the alleged inefficiencies of the international body,” according to Lawrence Gostin.

The WHO lost financial support and operational capacity, engaged in increased competition with other NGOs, and even faced open hostility from governments skeptical of the UN. Waning American support for the WHO (the U.S. contributed approximately 25% of the WHO’s budget in the mid-1980s) during the Reagan and the George H.W. Bush administrations was certainly a contributing factor to the weakening of the WHO.

The emergence and reemergence of novel diseases since the late 1990s, however, has created a new epidemiological landscape that gave renewed purpose to the WHO in guiding international efforts to control disease outbreaks and providing humanitarian aid.

The 1996 outbreak of Ebola in Kikwit, Zaire tested the limits of the WHO’s operational capacity—and the slow response resulted in the development of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Program, which was tasked to prepare a plan to mobilize resources and personnel rapidly in response to a disease outbreak.

The WHO remained reliant on member states’ willingness to share epidemiological information, however. When governments concealed information, as the Chinese did during the outbreak of SARS in 2003, the consequences were dangerous—allowing the disease to spread internationally.

In response, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution in 2005 that allowed the WHO to declare a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” that would allow the WHO the authority to denounce countries that attempted to conceal epidemics, and strengthened support for detection, notification, and analysis of a public health emergency.

The WHO was much more effective in its rapid response to subsequent outbreaks of influenza in 2005 and 2009.

This acceleration was the result of a renewed global commitment to public health that began in the late 1990s and continued into the first decade of the 21st century. Western European (U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair and French President Jacques Chirac) and U.S. government leaders from both parties (Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama) reaffirmed their support for the WHO’s mission financially.

Strong leadership under Norwegian director-general Gro Harlem Brundtland, who served in the role from 1998-2003, reorganized the WHO into a more efficient organization with greater global reach through public-private partnerships. Her successor, the South Korean physician Jong-wook Lee, continued to call on the support of a “global community” in the promotion of public health.

More controversially, however, Lee established a Commission on the Social Determinants of Health in 2005 with a mission to root out the causes of public health problems and offer suggestions on new approaches to closing health disparities. The Commission’s 2008 report called for more equity in health resources and thus made the health outcomes of poor countries more central.

However, the report never became a priority for the WHO. There are many possible reasons why: Lee died suddenly in 2006, and his successor, Hong Kong-born physician Margaret Chan, whose expertise was in infectious disease control, was far less interested in the Commission’s work. Second, medical professionals still grappled with the intangibility of social rather than biological factors that influenced health.

Third, conservative politicians rejected the “ideology” of a more egalitarian world. And finally, the 2008 financial crisis tightened global spending across all sectors, forcing the WHO to choose its initiatives more selectively. Development goals, like Universal Health Coverage, took the hit (even though it was billed as cost-saving).

Thus, in the second decade of the 21st century, much of the work of the WHO continued to focus on infectious disease surveillance and control. And in large part it was successful.

In 2009, under revised International Health Regulations, the WHO warned that an outbreak of H1N1 influenza A (the same strain that caused the 1918 pandemic) was a Public Health Emergency of Concern (PHEIC), setting the world on high alert and establishing the foundation for the 2011 Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework.

In 2014, the WHO similarly declared an outbreak of Ebola in West Africa another PHEIC, although not before the death toll had exceeded 1,000 worldwide, leading to significant international criticism of the WHO’s relatively slow action. In 2016, Zika virus was declared a PHEIC in the Americas, and the outbreak was contained within the year.

And, of course, in 2020, COVID-19 became the latest PHEIC. While the response to the COVID-19 pandemic was far from perfect, the WHO played an important role in the development, production, and equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines.

In 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the WHO to undertake its second convention on pandemic prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery to update its International Health Regulations for the future.

Planning for the future requires learning lessons from the past, as Director-General Ghebreyesus said in 2023. One important lesson we can learn from the history of the WHO is that while the roots of modern public health might be found in Europe in the mid-19th century, since the early 20th century the United States has been a global leader in the promotion of international public health.

Yet rather than learning lessons from the past, in 2025 we are instead seeing the fragmentation of global health initiatives. With President Donald Trump’s announcement of the United States’ intent to withdraw from the WHO on January 20, 2025, the United States has now set the WHO on a path into an uncharted future with potentially dangerous consequences.

Marcos Cueto, Theodore Brown and Elizabeth Fee, The World Health Organization: A History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

John Farley, Brock Chisholm, the World Health Organization and the Cold War (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008).

“Four Decades of Achievements: Highlights of the Work of the WHO.” (Geneva: The World Health Organization, 1998).

Lawrence O. Gostin, “The World Health Organization on Its 75th Anniversary,” Journal of the American Medical Association Health Forum 4 (2023): e231568.

Lawrence O. Gostin et al., “The WHO’s 75th Anniversary: WHO at a Pivotal Moment in History,” British Medical Journal Global Health 8 (2023): e012344.

Michale McCarthy, “A Brief History of the World Health Organization,” The Lancet 360 (2002): 1111-1112.

Randall M. Packard, A History of Global Health: Interventions into the Lives of Other Peoples (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Javed Siddiqi, World Health and World Politics: The World Health Organization and the U.N. System (Columbus: University of South Carolina Press, 1995).